The last eruption was in the 19th century, a blast that sent a gigantic cloud of steam and ash into the air. But that was nothing to the big bang that occurred about 12 million years ago, the one which, in effect, created the island of Nisyros by severing it from the mainland of Asia Minor.

One of Greece’s two volcanic islands (the other, of course, being Santorini), Nisyros lies in the center of the Dodecanese 11 nautical miles south of Kos. It is shaped like an inverted cone. At the heart of the cone in the Lakki plateau is the caldera – a huge hole in the ground where the volcano once stood. The caldera is pock-marked with five craters and is now considered safe enough to be a tourist attraction, even though it still has some fire in its belly. Sulphuric steam leaks from fissures and holes in the ground, staining everything yellow, and turning the scene into a Hollywood moonscape overhung with the stench of rotten egg.

In legend, the groaning beneath the floor of the caldera was attributed to Polybotes, a giant crushed by the Titans under a boulder torn from Kos.

Today the island’s volcanic propensities are causing an upheaval of another kind, a battle between the islanders and Athens over whether to build a geothermal-powered electricity plant in the caldera. Local tempers are heating up as a team of European engineers and chemists works to complete a pilot project that was financed by an EC grant of ten million dollars.

The project is being supervised by DEH, Greece’s public power corporation, which for the past decade has been trying to exploit the country’s geothermal energy as an alternative source of electrical power. For a small country like Greece which must import nearly all of its oil, the harnessing of nature to produce energy makes good, economic sense.

DEH’s faith in geothermal energy is borne out by Ibrahim Kasap, a petroleum engineer involved in the Nisyros project. Kasap, who is employed by the Italian-based company Dal Spa and has worked on geothermal projects in Turkey, the Philippines, Salvador, Nicaragua and Japan, among others, said that energy potential on Nisyros is enormous.

“We could provide enough power up here to supply electricity not only to Nisyros but to three or four other islands in the vicinity,” he said in an interview conducted on the site of the project’s field station.

Five wells have been dug at depths of 1000-1500 metres. The steam and water that are drawn off by the wells – steam on one side, water on the other (the brine is four times saltier than seawater) – are constantly monitored and analyzed. An environmental study, supervised by the University of the Aegean, is also being conducted to discover which gases and metals are to be found in the emissions.

“All our work has shown that Nisyros could have a good, clean power station if it wanted to, one that would provide electricity at 30-40 percent of the present price,” said Kasap. “These five wells could supply a power plant with a minimum of ten megawats an hour – ten times the amount consumed each hour on Nisyros.”

All the professionals attached to the test project have sung its praises, but to no avail. The 800-strong population of the island opposes it, passionately and vociferously.

“They are going to poison us all if they build that station,” said a farmer when asked his opinion. A bar-owner put it another, more graphic way when Kasap entered his place one night. Stop spoiling my island!” he shouted at him, shaking his fist menacingly.

The islanders have good reason to mistrust the project, as they can point to DEH’s geothermal fiasco on Milos in the Cyclades.

There, DEH (working in conjunction with a Japanese company) built a couple of geothermal wells, the first near the village of Zefyria. Promises were made that the well would not pollute, that the harnessing of the geothermal power would bring cheap energy, increased prosperity and abundant fresh water for use in commercial greenhouses.

The opposite happened. The prevailing winds brought such a strong smell from the well that the village had to be abandoned. The farmlands around Zefyria became polluted, killing crops and animals alike. In the end, the Miliots not only took to the streets to demonstrate against the project but actually dynamited the chimney, causing DEH to shut down its entire operation on the island.

‘ ‘DEH made major mistakes on Milos, no doubt about it,” said Bruce Kilpatrick, the Australian-born site chemist on the Nisyros job. Kilpatrick (who is employed by the British firm Merz & McClellan) spent six months on Milos before transferring to his new post. “They were warned against sinking a well right on top of Zefyria, if only because of the way the wind blew and carried not just the sulphur dioxide smell but the noise made by the ventilating system.

“DEH ignored the engineers’ advice and paid a big price for it. But these mistakes needn’t be repeated here,” he continued. “The power station we’d like to see built in the caldera is far away from any villages and the prevailing wind blows south, toward the uninhabited part of Nisyros.”

Kilpatrick also pointed out that gas is vented all the time through the caldera’s holes and fissures. “The gas is there; we’re not creating it. It just becomes more visible and concentrated when vented through a chimney,” he explained.

Kilpatrick felt it would be a tragedy if Nisyros’ geothermal potentialities were left untapped. “The project would not only create 40 to 50 new jobs, but would also provide all the power for the desalinization plant Nisyros is planning to build.”

Water is a terrible problem on Nisyros. At present, even though the island is remarkably green and lush,fresh water must be shipped in from Rhodes and Kos and delivered to wells and houses by a complicated system of trucks and pumps.

“Attempts have been made to build dams to save the winter rainfall and provide us with our water, but the volcanic soil just seems to soak everything up like a sponge,” said Ilias Hadzimichalis, the mayor of Mandraki, Nisyros’ main village.

“Right now, Nisyros pays two million drachmas (about $125,000) a year for water,with the Greek governmenttaking care of the balance (13 million drs).It’s a lot of money and we certainly would like to save that amount – but not if we have to go through what Milos did,” he continued.

Hadzimichalis was more cautious than most about condemning the Nisyros geothermal project out of hand. ” I trust the engineers when they tell us we can have clean and cheap electricity. I just don’t trust DEH, that’s all. I don’t believe they will do a good job of building and running the plant.”

As for DEH, its on-site supervisor declined to be interviewed for this story, and the company’s public relations man I met with in Athens talked only on the condition of anonymity.

“The problem is that with the current political situation in Greece and a makeshift government in power, DEH is operating in a vacuum,” he said. “We know important decisions must be made about Nisyros and that we need to go out and talk to the people and educate them as to the positive side of the project. We must win them over to our side, but without real leadership from the top, nothing can be done. We have lots of chiefs, but no chieftain. No one wants to take the responsibility for Nisyros and that’s why things are dragging on there.”

Things are progressing so slowly on the island that, according to Kasap, “At our present rate of work, I calculate that it will take another 40 years to build the power plant.”

Kasap said that he has never before encountered such problems as he has on Nisyros. “Geothermal is the cleanest and cheapest energy in the world, after hydro energy. It’s what Nisyros and all the islands around here need – yet the mindset of the people, and of DEH itself, seems to be completely against it. I ‘ve never seen anything like it in my 20 years in the business.”

When not letting off steam about the GT project, the Nisyrians are an immensely cheerful and happy people (among the Greeks they are known as elefromyaloi – lightheaded or scatterbrained). They don’t work too hard and welcome any excuse for a party, often celebrating weddings and baptisms for three days.

Yet there are few signs of poverty on the island, if only because more than 7000 Nisyrians live abroad (mostly in Astoria, New York, and Melbourne) and send money back home. The island also shares in the profits made in the mining of pumice on Yali, a tiny island opposite Mandraki which is worked by the locals.

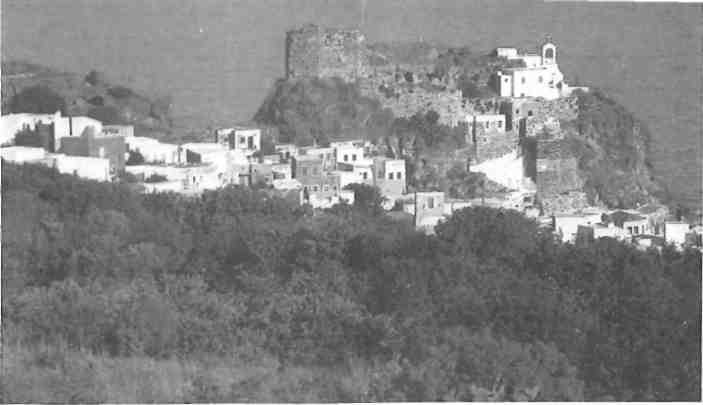

Nisyros is preternaturally beautiful, Mandraki, situated on the northwest corner of the island, is built on the edge of the sea and is full of resplendent white houses, serpentine streets, lush gardens and open-air tavernas.

Two of Nisyros’ three other villages, Nikia and Emporios, perch atop mountain peaks at either end of the caldera and are tiny, jewel-like places. Paloi, down on the curving east side of the island, is a fishing village with pleasant tavernas and an enclosed harbor where private yachts often drop anchor. Near Paloi is Loutra, one of the two thermal baths on the island (the other is being rebuilt). Loutra has rooms to rent and can also boast of an excellent taverna.

The Nisyrians turn out full force on 15 August, the Feast of the Assumption. Mandraki’s church of the Virgin Mary wines and dines everyone on the island for free, with dancing and roistering from dusk to dawn.

The laughter and jollity only cease when the question of geothermal energy is raised. Those are fighting words on the island – and chances are the fight has just begun.