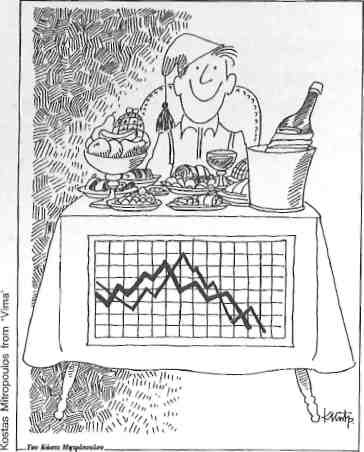

Hardly had January’s 11-day garbage strike been settled and the mountains of refuse hauled away, than the aroma of a more serious decay began to mount. There was growing talk of a general malaise. At a point when the economy was in a critical state, with the consumption of imports, unemployment and inflation rising, and production, efficiency and performance dropping, the General Confederation of Greek Workers (GSEE) began a 24-hour strike. This affected commerce, private industry as well as state-owned enterprises such as utilities, banks and public transport. On the same day, 25 January, Olympic Air¬ways called a walkout along with seamen in Piraeus who left passenger boats, freighters and cruise ships tied up and idle. With the ecumenical government of Professor Zolotas desperately trying to reduce the 14 percent inflation (three times the EC average), GSEE was demanding a 19 percent rise in wages. The cost of the one-day strike was estimated at 14 billion drachmas.

The prime minister accused unions of dynamiting the economy and jeopardizing the long-term interests of the workers themselves.

Since long-term interests were far from the minds of unions, which negotiate new contracts with their employers early in the year, another wave of strikes was called for the 6 and 7 February. For its noticeable effect, it was led by employees of DEH. Much of Athens was plunged into darkness, computer programs went haywire, scores were stranded in lifts, and trolleys, brought to a halt while passing one another, blocked thoroughfares. The only positive response came from drivers who believed that vehicle circulation ran more smoothly without traffic lights.

At the same time, 15,000 doctors and nurses joined strikers for higher wages, leaving hospitals, as it was aptly put “operating on skeleton crews”. A work stoppage by air traffic controllers caused delays for over a thousand international and domestic flights.

During this state of confusion and apathy, Professor Zolotas warned that social unrest in the country was scaring off foreign investment, particularly at a time when events in Eastern Europe made the potential for investment there seem increasingly attractive. In reply, GSEE leaders complained that the government was finding fault with labor demands. The working classes, the Confederation maintained,were not to blame for the sad state of the country’s economy. Such statements now were made mainly for the ears of voters, since the country last month was moving into its third pre-election period in the last nine months.

It was not strikes alone, however, that were hampering the operations of the government. Broadening signs of social unrest were being felt elsewhere. In the pause between the two major waves of strikes in late January and early February, anarchists and terrorists began operating quite openly.

Protesting a court decision which declared innocent a police officer who had shot and killed a youth in a riot four years ago, students gathered in an orderly protest. Shortly after they dispersed, however, unruly mobs took their place and vandalized the Polytechnic. Claiming they, too, were students, the anarchists began to riot while at the same time claiming asylum which students are allowed by law to enjoy within the precincts of the School.

With support withdrawn on the issue of unrest among youths by two of the three political parties backing it, the government felt powerless to evict those who had occupied the campus. As a result, law-abiding Athenian citizens passing in the vicinity either on foot or by bus suffered the humiliation of hav¬ing their identity cards demanded of them by Molotov-cocktail wielding hoodlums.

The squatters eventually decamped, leaving the premises of the National Metsovion Polytechnic a shambles, strewn with rubbish and discarded syringes. A good deal of the furnishings had been carted away to be sold in the flea market around Abyssinia Square.

No sooner had this series of events taken place, than five masked pistol-toting men strode into the War Museum and walked off with a cache of World War II armaments. On 5 February the all-too-familiar 17 November terrorist group claimed credit for this escapade, and lest the authorities be unable to put one and one together, it assured the avid readers of its manifestos that it, too, was responsible for the swoop on an ammunition dump near Larissa two months ago. Ballistics experts queried on the matter were of the opinion that although the bazookas were of World War II vintage, they could be made serviceable again if put in the hands of skilled mechanics. Athenians were in¬trigued to hear that the weapons could bring down substantial-sized buildings. With raids on police stations and army depots, 17 November may have amas¬sed a tidy little arsenal. They like to circulate photos of neat pyramids of piled up armaments, like supermarket displays, over which hang photos of Che Guevara and Karl Marx.

The following day, Minister of Public Order, Dimitris Manikas, said, “I do not exclude the possibility that the ultimate goal of the terrorists is to prevent the staging of the 1996 Olympiad in Greece.”

This led to speculation that the terrorist group was actually stockpiling its materiel for 1996 in order to make the Golden Olympics truly unforgettable. If the purpose of terrorists and anarchists is to destabilize democratic process, they were doing well. A year ago the “Lebanonization” of Greece would have been thought to emanate from the lunatic fringe; it is no longer thought of as being so far-fetched.

On 7 February, a New Democracy spokesman said that the Greek state was in the process of falling to pieces and that law and order were dissolving. Mr Papandreou, who had expressed cautious disapproval of the Polytechnic take-over, now said that ND was over-dramatizing the situation.

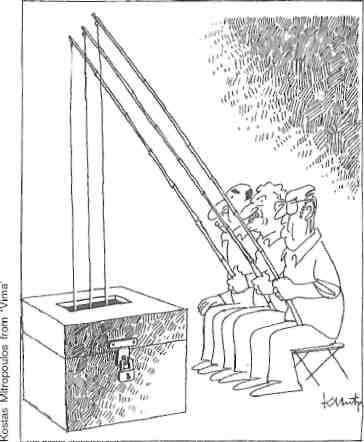

But Mr Mitsotakis would have none of this. At a press conference the day after, he claimed that Greece was rapidly becoming a Third World country though a paradise for anarchists. He criticized the ecumenical government of Professor Zolotas as submissive, and accused both PASOK and the Left Coalition of failing to sup¬port measures proposed by the government so long as they might in any way disturb their angling for votes. Mr Mitsotakis concluded on single note of hope: that the party would give full support to Constantine Karamanlis as its choice for President.

But within 48 hours even this straw in the wind eluded the hapless conservative leader when the Great Ethnarch turned down the proposal that he stand as Presidential candidate. In subdued but firm words, Mr Karamanlis condemned the whole political system and its personalities, including the leader of the party which he himself had founded in 1974.

Feeling hamstrung in every effort he had made to secure effective government, Mr Mitsotakis pulled his ministers out of the Zolotas government. PASOK and the Left Coalition could not but do likewise. Precisely at the end of its One hundred days’ after the 5 November elections, the Ecumenical Experiment collapsed, with nothing so dramatic as the Battle of Waterloo, but with the rug being pulled from under it in three different directions at the same time.

Such a coming to pass would have permanently toppled a lesser man than Professor Zolotas. He has proved to be pluckier (or perhaps just ‘less cautious) than Mr Karamanlis who, at a mere 83, is two years his junior. He immediately formed a new government made up of ministers from the former Grivas care-taker regime. Since he still had the tacit support of the three major parties, Mr Zolotas maintained that his government had only undergone a major reshuffling and not embarked on a new deal.

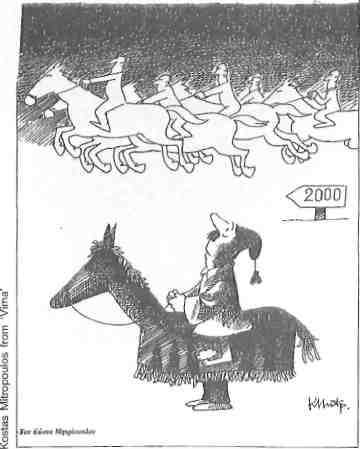

So, in pursuit of his impossible dream, Don Xenophon remounted his steed, and free of his three attendant Sancho Panzas, he cantered off to fight the good fight. Encountering Parliament on 17 February, he warned that if Greece did not get its act together – and fast – the 1992 EC integration would constitute yet another lost opportunity for Greece.

Suggesting that a reunified Germany would soon bring East Germany into the EC, the prime minister evoked a vivid picture of a stampede of Eastern European mustangs galloping into the European Community and the future, while Greece sat by idly rocking on its hobby horse.

As if on cue, the General Confederation of Greek Workers, announcing that the negotiations with the Federation of Greek Industries had reached an impasse, prepared for another debilitating nation-wide strike.