News of the 1821 Greek uprising against Turkish domination sent spasms of excitement through the newly created federal patchwork of cantonal Switzerland. Democratic and republican, it was one of the first countries to organize “Hellenic Committees” to aid the insurgent’s cause: many Swiss Philhellenes played unobtrusive but nevertheless key roles in the turbulent upheavals which led to the creation of modern Greece.

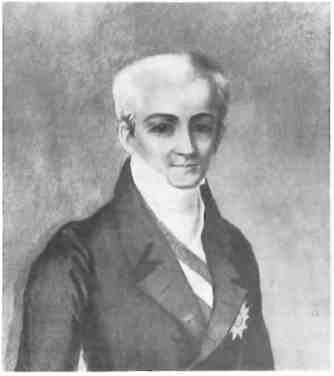

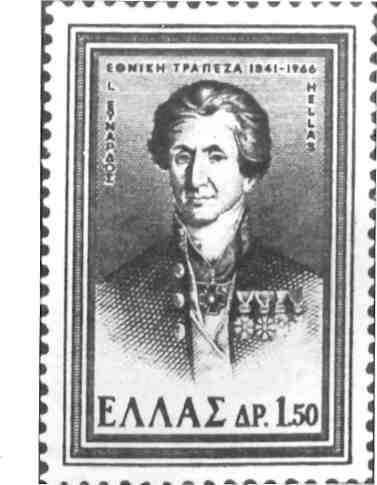

Ever since the exile of Napoleon, liberal circles in Switzerland, which cut across all social boundaries, had been fully aware of the growing Greek aspirations for independence. At that time, they themselves had petitioned the major powers for internationally recognized neutrality and frontiers which included the cantons previously annexed by France. Their hopes had been realized largely through the conciliatory but powerful influence exercised by the

Corfiot Count Ioannis Capodistria, then foreign secretary to Czar Alexander of Russia, and later to become president of Greece. He had also patiently and expertly ironed out the individual problems of each canton resulting in the acceptance of federalization.

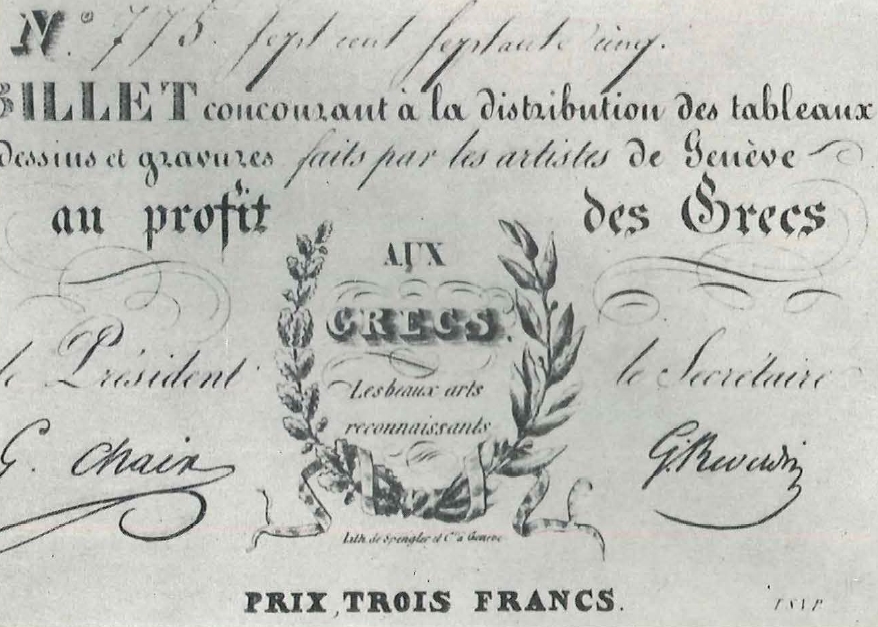

For his valiant efforts on their behalf, honorary citizenship was conferred on him by several-Swiss towns including Geneva where he later took up residence, making it his second home. His was the discreet, directing influence on the many Philhellenic committees which sprang up all over the country in the late autumn of 1821; not only in the cities of Zurich, Berne, Basle, Lausanne and Geneva, but in towns like Zug as well.

Almost immediately, Swiss volunteers made their way over the snowy passes to take ship from Marseille or Livorno. Some were soldiers, such as those who died heroically with the gallant corps of Philhellenes at the battle of Peta in July 1822, others were doctors or educationalists. Some returned to report on the chaotic situation prevailing there; with their vital information, aid was organized more successfully.

Switzerland’s position at the cross-roads of Europe placed it on the direct route for Philhellenes from more northern countries; at the frontier they were given lodgings and food, then passed on bearing notes of introduction from Zurich to Berne, Lausanne or Geneva where they were supplied with provisions and money to help them reach the nearest port. At one point the number of armed volunteers passing through was so great that it alarmed the internal security police. This continual generous outpouring of assistance reflected Swiss public opinion and concern. Catholics and Protestants alike united to help “the Christian faith and Greek freedom”.

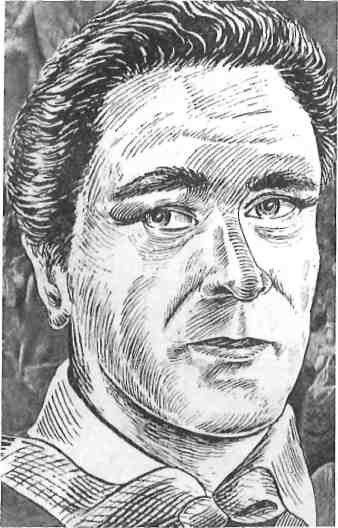

One of the first Swiss to head south was the outstanding Philhellene, Johann Jakob Meyer, a pharmacist from Schoflisdorf near Zurich, who had also studied medicine at Fribourg University but who had been expelled before graduating for “behavior unbecoming”. A liberal, fired with the ideals of freedom and democracy, he set out in 1821 and eventually reached Mesolonghi, which was to become one of the chief rallying points in defense of the Greek cause. There he stayed until the fall of the town five years later.

Competent, conscientious and extremely hard-working, Meyer participated in the founding of a local hospital at Mesolonghi, ran its pharmacy, embraced Orthodoxy (he had been a Protestant) and married a local girl, Altani, the daughter of a well-to-do inhabitant Georgios Inglesis, who helped finance the hospital. Probably because of his firm republican principles, Meyer was selected by the Benthamite Colonel Stanhope to edit the newspaper the Hellenic Chronicle. Stanhope found him “straight-forward, worthy of respect, able and educated” showing “all the good characteristics of his race.”

In the prevailing political quagmire, Meyer’s strongly held beliefs earned him many adversaries including Byron who called him a “petty tyrant” and lost no opportunity in levelling scathing criticism at him. On his part, Meyer addressed him as “Mr” Byron, wrote zealously against monarchy and attacked his opponents’ views through the newspaper which was esteemed elsewhere. It was the first to publish Solomos’ Hymn to Liberty which in part forms the Greek National Anthem.

Meyer maintained complete editorial independence throughout three-and-a-half years of publication and toadied to none. This was no mean feat in times of revolution — nor even today. His high standards were recognized and honored on the centenary of his death by the “Union of Journalists in Athens” which erected a column in his memory at Mesolonghi bearing the inscription: “A writer who fought in the front line with pen and weapons for the freedom of Greece. When in this town luck abandoned him, he was buried in a grave of virtue on 30 April 1826.” A glittering group of VIPs, including the President of the Republic, attended the unveiling — testimony to his lingering influence. Today a street in Athens as well as one in Mesolonghi, (where there is also a square dedicated to the Hellenic Chronicle), bears his name.

Behind this humanitarian rescue, was the greatest of Swiss Philhellenes, the influential and immensely wealthy banker from Geneva, Jean-Gabriel Eynard.

Although he never set foot on Greek soil, it is difficult to plumb the debt which modern Greece owes this altruistic benefactor. A life-long, ardent Philhellene and loyal friend and supporter of Capodistria, he devoted all his time, energy and a considerable part of . his fortune to the revolutionary cause. His deep love of Greece did not show itself in impassioned romantic idealism — being Swiss — and his concern was expressed tangibly in practical necessities. Having, in his early twenties, lived through two short sieges during the Napoleonic wars, he was well aware of the strains on human frailty during times of upheaval. He therefore acted as co-ordinator not only of the Swiss committees but also those of all Europe.

By a truly amazing network of corres-pondents he was able to direct aid to the precise place it was needed most and to ensure that arms, medicine, food and money arrived in the hands of those who desperately required it. Endowed with outstanding ability to choose the right man for the job, he personally selected agents like Francois Mercet to carry out missions of distribution and report back to him. To a country devoid of even rudimentary medical services, he sent dedicated young doctors such as Louis-Andre Gosse who served with the navy and dealt heroically with the endless wounded and maimed as well as with plague, malaria and other indigenous diseases.

As unofficial ambassador of Greece to the governments of Europe, Eynard journeyed tirelessly to the main capitals; he arranged for Greek orphans such as the son of the hero, Markos Botsaris, to be educated in Switzerland; he rearmed Greek refugees from Moldavia and Wallachia and financed their journey to Greece.

As well as being the financial mainstay of Capodistria when he was chosen to be first governor/president of the fledgling state, he provided him with an invaluable secretary Elie-Ami Betant who ably handled copious correspondence from the presidential tent. Artisans for rebuilding work were dispatched south along with educationalists from the experimental school of Pestalozzi and Fellenberg at Hofwyl in an effort to graft some of their ideas which had so impressed Capodistria a few years previously, onto the skeletal Greek school system. He dispatched the first potatoes to Greece, which the locals eyed with much suspicion,to help feed the starving populace and contributed to the founding of a Greek national bank. When the major powers were secretly selecting a suitable prince to become the first king of Greece, it was Eynard,with his ear to the ground,who informed his old friend Capodistria.

Eynard was not motivated by hopes of personal glory or dark political machinations: he asked nothing for himself or his country. Even his satisfaction at seeing Greece become an independent nation was tempered by his disappointment over the imposition of monarchy. Nevertheless, he continued to aid the tiny state in any way possible. His only tangible reward was the Greek “Order of the Redeemer” bestowed on him for his outstanding services.

Many unsung Swiss heroes left their bones on Greek soil, while the known names appear among the fallen at Peta, Phaleron and Athens. Two renowned military leaders helped form the standing national army, Karl Wilhelm Heidegger from Zurich who fought with the Bavarians as Von Heidseck, and Emmanual Hahn who stayed on as adjutant to King Otto, returning home an old man to die in his bed at Interlaken.

Much has been written about Philhellenic support from the great states of Europe as well as American, but. few were as altruistic or did more to help Greece struggle onto the political stage than little Switzerland which itself at that time was still recovering from the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars.