The rather meager ruins of Eretria today do not easily conjure up an image of a town which was one of the centers of the Greek world. Apart from a well-preserved theatre of the 4th century BC, and a massive city gate of the Archaic period, there seems little at first to recommend the site for so exalted a status. Yet this coastal settlement of Euboea, with its bustling port and massive walls was one of the first Greek cities to outgrow its boundaries and found far-distant colonies. Together with its neighbor, Chalkis, Eretria established mercantile depots as far afield as northern Syria and centra! Italy, acting as agents for the importation of iron from Etruria and copper ore from Asia.

Eretria was flourishing when Athens was still a cultural and commercial backwater. A major power in the days of Homer, Eretria is included in the famous Catalogue of Ships in the Iliad – well ahead of the modest Athenian contingent. Though her fortunes were eventually eclipsed by the rising sun of Athens, there is much evidence of her prominence in the 8th century. Furthermore, there is evidence of an even earlier Eretria, though controversy continues regarding the site of the original town.

In 1964, the British School of Archaeology excavated a site some 16 kilometres up the coast from the town of the Archaic and Classical periods. At Lefkandi, the School discovered a mound rich in artifacts from late Mycenaean and early Geometric periods the close of whose chronology coincided with the founding of Eretria in the 8th century.

Archaeologists generally agree that the Eretria of the Lyric Age (8th – 6th century) was probably a colony of, or a resettlement from, the original town at Lefkandi. It was a wise move for the original Eretrians, for the present site posesses certain elements absent at Lefkandi essential for the commercial settlement that Eretria was to become.

Though there was the disadvantage of swamps in the area that had to be drained to ensure the health of the city’s inhabitants, there was also a spacious natural harbor, in its heyday one of the busiest in the eastern Mediterranean and the source of Eretria’s wealth. Another advantage was the city’s access from the south to the large and fertile Lelantine plain. This rich agricultural expanse caused a dispute between Eretria and her neighbor, Chalkis, and the Lelantine War lasted a century. Though Chalkis finally emerged victorious, the alliances formed by Eretria with other cities during the conflict, which later became a Panhellenic struggle, were important to the town’s subsequent history.

Her embroilments in the Persian Wars had long antecedents. The assistance she gave to the Asian Greeks in their uprising against Darius in 499 was in return for the support given her by Miletus in the Lelantine War. Samos, however, which backed Chalkis, betrayed the Greek cause in the Ionian Revolt, deserting at the last moment and precipitating the defeat of the Greek fleet in the crucial naval battle of Lade.

Though successful in putting down the rebellion, Darius didn’t forget the provocative roles played by Eretria and her neighbor, Athens. The two city states had rendered substantial aid to the Ionian Greeks in their bid for freedom, providing ships for the campaign at sea, and land troops for the march inland that led to burning of the Persian metropolis of Sardis. This affront festered in Darius’ heart, and in 490 he launched an expedition against Greece whose objective was the destruction of Eretria and Athens.

Both cities had to contend with divided councils and potential traitors within their own gates. Both cities re-solved in the end to resist the Great King. The Eretrians retired behind their walls and managed to hold out for six days against the Persian armada. In the end they were betrayed. Two dis-affected aristocrats, Philoagros and Euphorbos, contrived to open the gates of the city and admit the invaders. The population was enslaved, the temples and civic structures burned. The Persian forces then sailed south and beached their ships on the east coast of Attica at Marathon.

Though the Greek victory saved Athens from fire and sword, it was too late for Eretria. Yet there were apparently enough who escaped servitude to reform something of a nucleus of a resurgent Eretria. Herodotus reports that Eretrians fought ten years later at Salamis, contributing a modest seven ships, and at Plataea, fielding 600 hoplites for that decisive land battle.

Eretria’s great rival, Chalkis, had fallen under the control of Athens before the Persian Wars, but Eretria had managed to retain her independence and enjoyed for awhile amicable relations with the Athenians who helped them to refound their city. But with the growth of Athenian imperialism, her status as an ally gradually was reduced to that of subject, and she was eventually required to pay her share of

tribute to Athens as leader of the Delian League.

Deep resentment smoldered in Eretria, as her mercantile wealth was siphoned off to adorn and strengthen her former friend. With the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, more burdens were placed on her, as she was required to furnish ships and men to fight for Athenian supremacy.

Eretria finally betrayed Athens. In 411 BC, during a naval engagement off her shores, the Athenians were defeated by the Spartans because of Eretria’s refusal to furnish supplies; when Athenian sailors sought refuge in Eretria, they were massacred.

Following Athens’ defeat, Eretria flourished again. New building projects were carried out, and the population increased to the level of its former heyday, of about 40,000 souls. The theatre, whose remains can still be seen, is of this period.

Though a time of material prosperity, the fourth century was rife with political instability. Eretria had a sucession of tyrants, the last of whom, Kleitarchos, was driven out of the city in 340. Ironically, it was Athens, now a champion of liberty, that forced him out of power.

Two years later, Athens and Thebes were defeated at Chaironeia by Philip of Macedon. Under Macedonian hegemony, Eretria experienced a great revival of artistic and intellectual activity. A philosophical school, founded by Menedemos, though a disciple of Plato, was really a continuation of the Eleatic tradition. Life was peaceful and orderly. As Rufus B. Richardson, who excavated here with the American School in 1891, remarked drily, “the Macedonian period was a good time for the philosophers to sit and think.”

On the Eretrian Exiles We who left long ago deep-surging Aegean, Now lie in the plains of far Ecbatana. Farewell, renowned Eretria which once was our country! Farewell, Athens, neighbor of Euboea! Farewell, beloved sea! Plato

Sacked by the Romans in 198 BC, Eretria yet prospered once again, with her harbor active and her ancient walls intact. Then she took the wrong side for the last time, supporting the Pontian King Mithridates in his revolt against Rome. The Romans destroyed the town again. It was the end. The destitute survivors of the final catastrophe couldn’t keep the swamps drained. They became bogs of pestilence and the population was decimated by malaria.

For nearly 2000 years Eretria disappeared from history, only to vaguely re-emerge with her once renowned name corrupted to Aletria. As a young man in 1814, the British architect Robert Cockerell (who much later designed the Ashmolean Museum and the Bank of England) made a map of Eretria which was as topographically accurate as it was archaeological fuzzy. If the plight of the Eretrian exiles gave literary fame to the ancient city in the epigram of Plato, it was another incidence of exile that brought Eretria briefly back into the limelight in modern times.

In the enthusiasm for antiquity awakened by the War of Independence, Eretria won back her ancient name, but only for a few years. The terrible massacre of Psara by the Turks in 1824 created a refugee problem which was only solved, and that incompletely, ten years late when King Otto’s architect Eduard Schaubert suggested making the site of Eretria a model city for the island exiles.

As a result Eretria, along with Athens, became the only neoclassically planned city in Greece, and was redubbed Nea Psara. The grandiose project only partly materialized, and the present little town with its long, straight avenues and open areas that were designed as squares, gives the somewhat rumpled appearance of a body dressed in a suit of clothes far too large for it. Its straggly lines of limp eucalyptus, planted in lieu of nobler trees, give the village a scruffy charm which was lovingly captured, by its resident painter, Spyros Vassiliou.

Modern Eretria made its first news when Christos Tombras, the greatest Greek archaeologist of his generation, opened some tombs there in 1885.

Six years later, systematic excavations began under the American School of Classical Studies. In four seasons, it cleared the small temple of Dionysos, the gymnasium and the very important theatre.

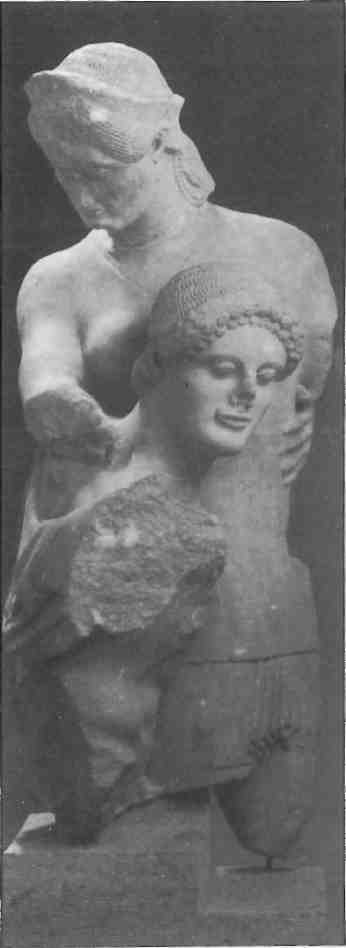

In 1897, Kourouniotis and the Hellenic Archaeological Society uncovered the remains of the temple of Apollo Daphnephoros whose pediment statues, though fragmentary, are superb examples of late Archaic art. The famous Theseus and Antiope which was found here at this time and is now in the Chalkis Museum, was a focal point of an exhibition that toured the US in 1987-88.

The same season saw the partial excavation of the great Western Gate and in 1915 Nikos Papadakis cleared the Tholos and the Sanctuary of Isis.

The major excavations of modern times, however, began in 1962 when the Greek Archaeological Service invited a consortium of Swiss universities to work in Eretria. Today it is the oldest Swiss archaeological mission in the world. Excavations began in 1964 under the direction of the dean of classical Swiss archaeology, Professor Karl Schefold of the University of Basel.

The early seasons involved young scholars who became well-known in archaeological circles in Greece: the late Paul Auberson, Clemens Krause, Ingrid Metzger, Claude Berard, Gabriele Passardi and many others. In 1983 the Foundation of the Swiss School of Archaeology was formed under the direction of Pierre Ducrey.

Among the major excavations of the Swiss have been the monumental and intricate Western Gate with its moat and wide varieties of wall. Altered in five major stages over a period of 500 years, it is the most elaborately rebuilt fortification in Greece. Three major complexes of aristocratic mansions have come to light,the House of the Mosaics and no less than five different temples of Apollo.

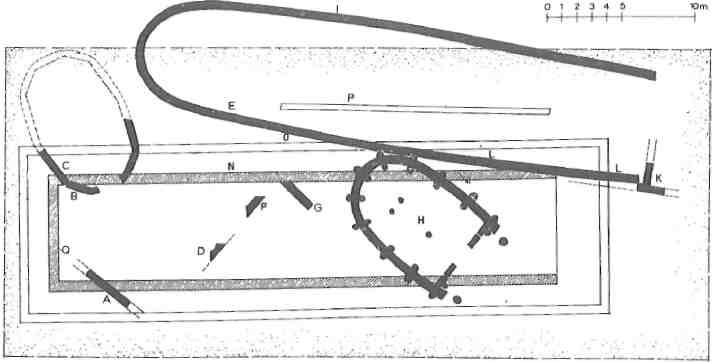

The last of these temples in date -and of course, most visible today – is of the Late Archaic period. Narrower and shorter, the Early Archaic temple (about 620 BC) lies entirely within the perimeter of the later temple. Next to this structure, somewhat off-axis, is yet an earlier absidal temple of the Geometric period and the largest of its kind in mainland Greece of which Euboea can be said to be a part.

The most intriguing structures, however, are even older, and they cast light on a curious and famous passage in Pausanias which has always puzzled scholars.

“They say” Pausanias writes, “that the most ancient shrine of Apollo was made of sweet laurel with branches brought from Tempe and that of the second was made from bees, and the third from bronze… As for the story about building a temple out of laurel and of beeswax, I shall not even begin to tell.”

At a level yet lower that the Early Archaic temple, a modest wooden structure was discovered in the 1970s on a stone base with a portico supported by two columns similar to the terracotta models of temples found at Perachora, the Sanctuary of Argive Hera and Thermon. The frame was held up by three interior columns placed like a triangle and enclosing walls of woven branches: hence the story of the shrine of laurel.

Then, close by, a yet older, small structure came to light: an octagonal-walled building with a single entrance, precisely in the shape of a honeycomb: hence the story of the shrine made from bees…

In recent years, Greek archaeologists have again been active in Eretria under the Ephor of Euboea, Efi Sapouna-Sakellaraki. More houses of the 4th century with peristyle courtyards and large assembly rooms have been excavated, work on the Sanctuary of Isis expanded and cemeteries have yielded important funerary ceramics.

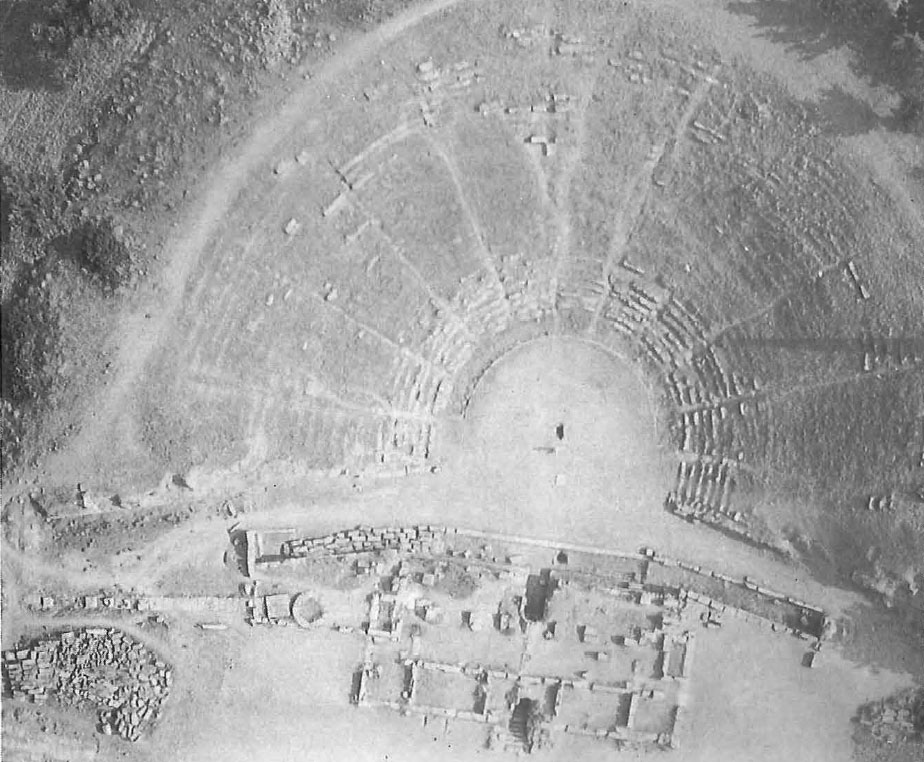

Today, the most physically prominent aspects of Eretria’s remains are the theatre which seated 6,000 and the massive polygonal walls encircling the acropolis.

The theatre shows three distinct periods of construction, but its prime was evidently the late 4th century. It shows a number of interesting features, including a vaulted passageway under the stage that led to the center of the orchestra, the so-called “ghost walk”, that provided for the timely materialization of gods and demons.

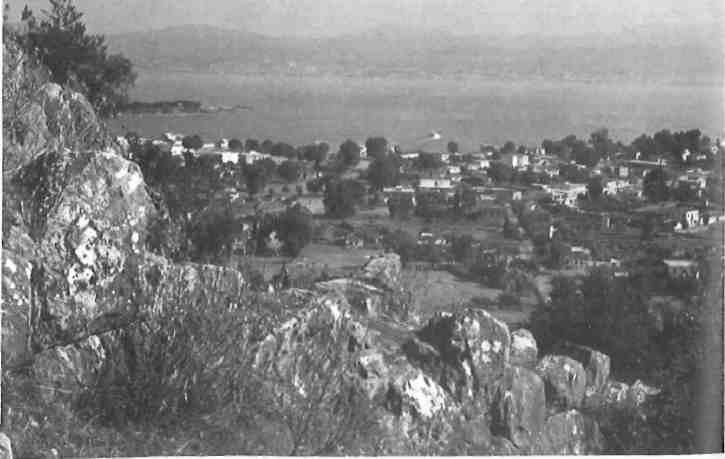

Proceeding uphill from the theatre, one can see, from a distance, through the pine and olive trees, the great walls of the acropolis. If one follows the line of wall to its rocky summit, the reward is a splendid view of the ruins of Eretria, the modern village on the harbor and the Attic hills across the gulf. Goats and sheep graze on the slopes below, and the Lelantine Plain stretches out to the north. From this height the strategic brilliance of the site is evident,and its natural beauty is striking.

There may be a moment of melancholy while reflecting on the final tragedy and eventual oblivion of this vigorous city, but Eretria’s heritage is not lost to us. Her prominent role in the history of Archaic and Classical antiquity is being continually clarified by excavation and research.

The site of ancient Eretria is less that 90 minutes from Athens by car. From the National Road, one can drive right across to Euboea, taking the Schimatari turnoff to cross the Euripos Channel via the bridge at Chalkis. From here, Eretria is about a 20-minute drive south along the coast. As well, car ferries are available from the village of Scala Oropou on the Attic mainland and also easily accessible from the National Road, and make the sea crossing in less than half an hour.