Out of the East came three kings, — not the biblical Magi bearing gifts for a unique boy-child, but Hellenistic rulers from Pergamon paying homage to what they believed to be the greatest city on earth and the cradle of their own remarkable culture-Athens. Being nouveaux riches dynastic rulers first, and wise men second, their awe and beneficence were not wholly altruistic: as their proferred buildings and monuments rose to adorn and glorify the sacred rock of the acropolis, so too were their own names and largesse ever more subtlely linked to Athenian history and immortality.

Pergamon, an inaccessible fortress town in Asia Minor, housed, like an ancient Fort Knox, the treasures of the Seleucid dynasty under the custodianship of its vassal, the eunuch Philetaerus. Taking advantage of the inter dynastic feuds and power struggles which engulfed Greece and Anatolia after the death of Alexander, this ruler quietly consolidated his hold on the surrounding area. When marauding Celtic mercenaries, the contemporary scourge of the area, came calling he sent them away with bloodied noses. Left in relative peace, he and his nephew Eumenes set about turning their rugged stronghold into a city-state — a “new Athens”.

Political raison d’etre influenced their dubious claim to be protectors of Hellenic civilization against barbarian chaos: from the first they expediently strove, through their selected use of architectural style and sculptural theme, to proclaim themselves the natural heirs of Athenian genius. These high-flown aspirations were not entirely groundless. Several decades later, when Attalus, son of Eumenes, became governor, the city had already been transformed into a flourishing cultural center acclaimed for its growing scholarship. A Doric temple dedicated to Athena Nikephorus crowned its own acropolis, while a palace, theatre, stoas and the beginning of a renowned library which rivaled that of Alexandria were planned out on a magnificent scale.

The Celtic menace however had not abated; three tribes some 20,000 strong and known collectively to history as the Galatians still terrorized the whole of Asia Minor from their newly-acquired homelands around Ancyra. Fishing in troubled waters, they sold their considerable sword power to the highest bidder while extorting an early form of protection money from all other cities. Attalus, judging the time ripe for a show of strength, refused to pay, and in the ensuing battles inflicted on them a devastating defeat. Such was the relief and gratitude of the neighboring states that no dynastic leader objected when he proclaimed himself “King” of Pergamon.

Despite his spurious title, judged alien and provincial in democratic Athens,the city gave him an enthusiastic welcome when he paid a triumphal state visit there some years later. To commemorate his military success, he dedicated a large monument which was allowed to stand on the acropolis itself — somewhere near the present-day Acropolis Museum — four groups of expressive Hellenistic bronze sculptures representing an Amazonomachy, a gigantomachy, the defeat of the Persians at Marathon and Attalus’ own recent outstanding victory over the Gauls. The message was clearly spelled out; here at last was a leader, drawn from Ionian stock, fit to stand alongside heroes like Miltiades; one who had the courage and ability to crush the barbarian threat. There was now, the marbles seemed to say, an undeniable historical connection between Pergamon and Athens.

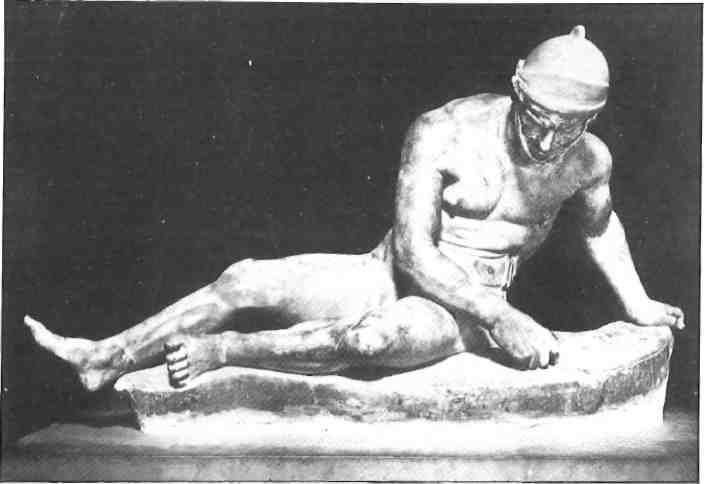

Although not all art scholars agree — and when do they ever — most believe that four marble, Roman copies in the Museo Nazionale in Naples were made from the original bronzes which formed part of Attalus’ memorial in Athens. The representative figures display signs of life in direct relation to their historical counterparts: the mythological Amazon and giant are dead; the Persian is gasping his last breath; the Gaul is, as it were, down but not out.

Continuing the now traditional Pergamene link with Athens, Attalus I sent his younger” son and namesake, “Prince” Attalus (II), to be educated there. He studied under the distinguished philosopher, Karneades, head of the famed New Academy, and he and fellow student Ariarathes (the future king of Cappadocia, another Anatolian state) so revered their eminent teacher that they erected a statue in his honor which stood in the ancient Agora. Only the base with its dedication has survived.

When Prince Attalus’ father died, his elder brother, King Eumenes II, further embellished Pergamon, extending its control to cover a wide surrounding area including the Greek cities on the coast 16 miles away. Securing political stability through an alliance with Rome, he attracted erudite scholars to study at his immense library which is said to have contained 200,000 parchments. He bought Greek works of art to adorn the temples and courtyards and was patron to outstanding artists from all over the eastern Mediterranean who made his city one of the most beautiful and influential of the Hellenistic age.

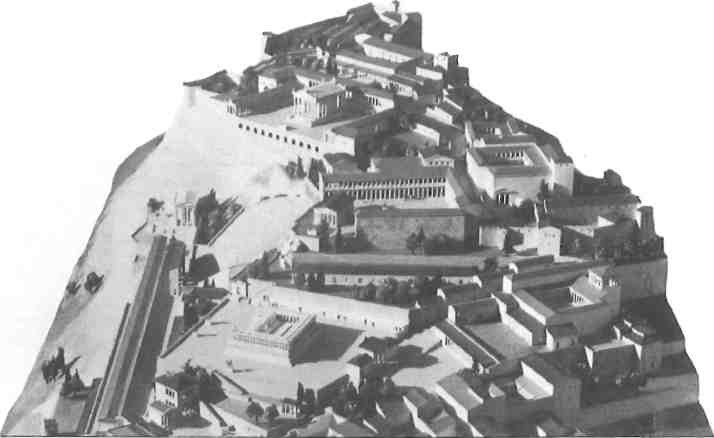

To celebrate a Pergamene chariot victory during the Panathanaic games of about 174 BC, he erected a quadriga on the steps of the Acropolis, opposite the temple of Nike which, later writers mention, included a portrait figure of himself. The bronze sculptural group has vanished leaving only an enormous plinth in situ to mark its existence.

Meanwhile, on the Acropolis’ southern slopes, his architects were constructing an elegant double-tiered colonnade to link the theatre of Dionysus to the Odeion of Pericles. A gracious place for Athenians to meet and converse with friends, this structure sheltered strollers both from winter rains and the scorching Attic sun. Time has not dealt kindly with the munificence of Eumenes, and only part of the rear wall remains.

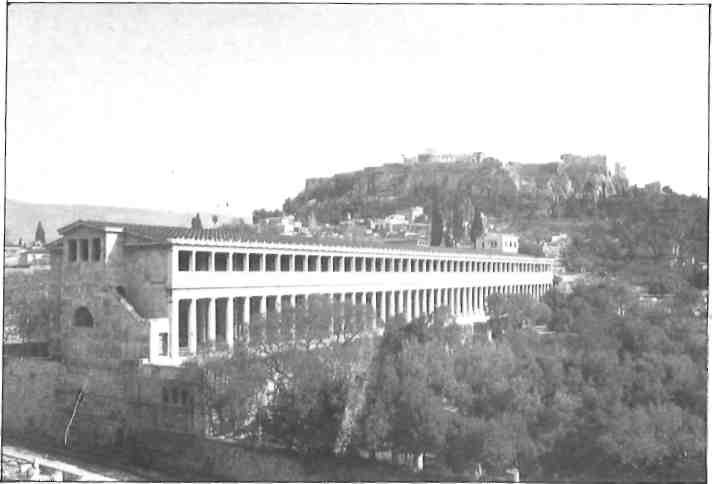

As much Athenian as Pergamene when he eventually inherited the title Attalus II, as patron of his adopted city he wished to participate in a rebuilding program planned for the east side of Athens’ Agora, and donated the stoa which bears his name.

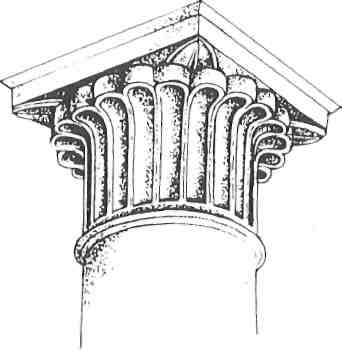

Confident of his own state’s ever-growing wealth and international renown, he made a deliberate effort, in contrast to his forebears, to create a recognizably Pergamene style through his use of innovative achitectural detail. His stoa, unlike the single-storied local ones, had two floors, each with a double colonnade; and the arch was introduced into Athenian architecture for the first time, as were the fleshy-leafed capitals on the upper and inner columns. These unusual features, together with its present-day pristine, penny-new appearance, and its alignment north/south as opposed to the usual, classical east/ west, all combine to* endow it with a somewhat alien spirit among the Agora’s older remains. However, at the time of its construction, it probably blended homogeneously with three other simpler Hellenistic-styled buildings which formed a square before it.

In 1953, when modern Athens was still licking its economic and psychological wounds following the privations of Nazi occupation and civil war, the American Archaeological School was searching desperately for a suitable shelter in which to house their precious finds from the Agora excavations. It was then decided to reconstruct the Stoa of Attalus with financial assistance from donors in the US; in particular John D. Rockefeller Jr, who contributed half the amount required.

With dedicated and patient research, using only materials taken from the original sources-limestone from Piraeus, Pentelic marble, and Attic clay, from which the tiles were molded, the stoa donated by “King” Attalus and “Queen” Apollonis of Pergamon slowly rose again. If today its marble columns do not resound to the bustle of trade — the original had 46 shops — social meetings or philosophical discussions; if crowds no longer jostle for position to watch the Pananthanaic procession file past on its way to the acropolis towering above, it is still well worth a visit. As the permanent Agora Museum, it displays superb, clearly-labelled finds spanning the centuries from Neolithic to Roman times. Outside, the ancient marketplace, which uninvitingly resembles a bomb site from above, exudes, at ground level, an air of peace and tranquility, a place to wander and reflect.

Histories and guidebooks struggling to convey over three millennia of often-innovative Athenian history and culture in restricted space on occasion miss out the 200-odd years between the death of Alexander in 323 BC and the sack of the city under the Roman general Sulla in 86 BC. Yet these were rich and productive centuries when Athens remained the mother-city and font of Hellenic culture for states as far apart as Syracuse and Bactria.

Its philosophical schools, which gave birth to Stoicism and Epicureanism, reigned supreme, their fame drawing students from all over the Greek-speaking world. Sculpture, painting, music and poetry flourished, Menander amused the populace with his new comedy, while ambitious kings governors, satraps and dynasts vied with one another to hitch their reputations, to its still-glowing star through donated works of art arid architecture — none more so than the three Attalid kings of Pergamon.