Having noted this, however, the photographs are so beautiful and the scraps of history presented by Marianna Koromila so tantalizing as to drive one at once to consult atlas and history books. These seldom travelled areas of Pontos are hardly known to the outside world today, except as the butt of endless and terrible jokes. Though we are familiar with Pontians through their misadventures in Greek off-color humor, many people would find it difficult to say where the Pontos is – unless of course they are survivors or children of survivors of the tragic exile visited on the inhabitants of the Pontos after 1922.

The ancient Greeks called the Black Sea the Euxinos Pontos, ironically (or hopefully) referring to it as hospitable when it is anything but. The Pontos, thus, is the Black Sea coast of Asia Minor, isolated from the rest of the world by the dangerous sea and the virtually impassible Pontic Alps, the mountains of Paphlagonia. The mountain slopes run steeply to the sea, and the narrow strip of coast was first colonized by Greek settlers from Miletus who founded Sinope in 700 BC.

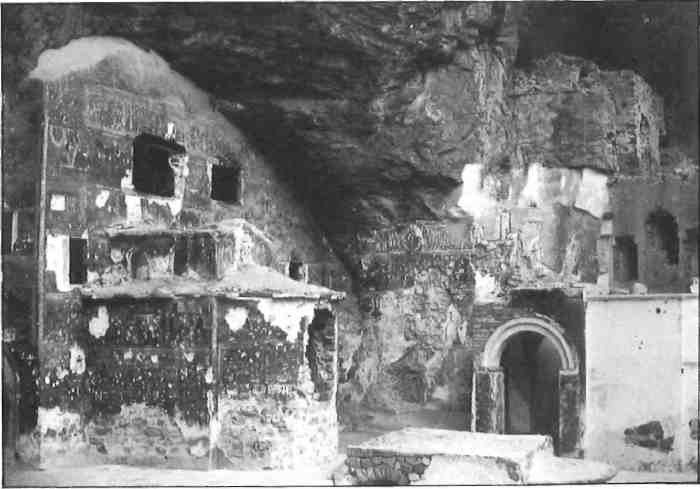

The three Athenian photographer friends have already produced Kifissia: Aspects of its Beauty and its Past, by Maria Karavia, published by the Society for the Protection of Kifissia. They first toured the Pontos with Marianna Koromila as their guide, on one of the tours of the cultural organization Panorama (Alexandrou Soutsou 4). Their photographs give stunning and tragic evidence of the enduring Greek civilization of the Pontos, not only from the 8th century BC to the fall of Trebizond in AD 1461, when it was taken by Mohammed the Conqueror; but also from the fall of Byzantium to the present day – to 1922 and the exchange of populations. The small basilica of Ayia Anna in Trebizond, which still survives and whose photographs are there for us to wonder at, was built in AD 883-884 and was continuously used by the Christian population until 1923.

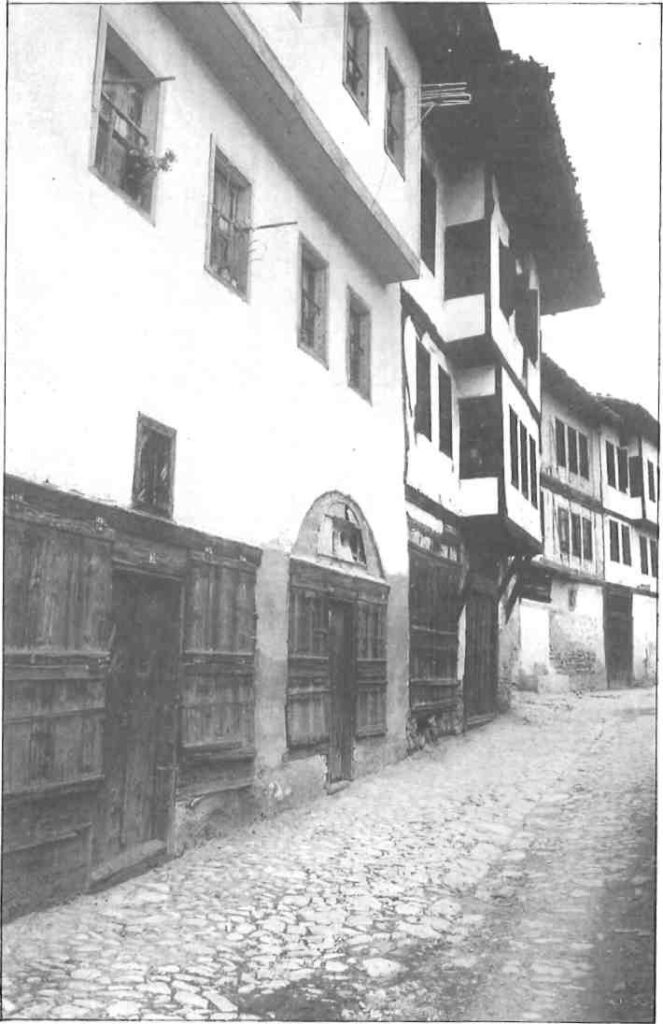

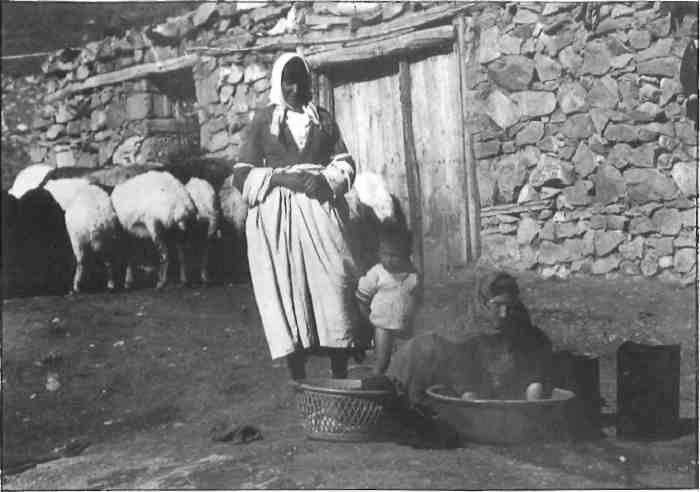

The really excellent color photos give example after example of Greek houses and schools built at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, still standing, some abandoned, others used as schools or museums or occupied by peasants who moved there subsequently.

The photographs record the incredible richness and diversity of remains in an area whose history covers more than two millennia. Marianna Koromila struggles in her text to compress all this history into manageable proportions without losing the flavor and texture of the landscape and of her historical outlook. Occasionally overwrought, but generally moving and descriptive, her text points out that these areas, only recently opened by NATO roads to more casual travelers, will soon be visited by tourists who will have no idea of what they are seeing. Particularly impressive is the list of Greek place names and their worn down Turkish equivalent: Trapezus=Trabzon, Ionopolis=Inebolu, Sinope=Sinop, Ayios Nikolaos=Ainikola, Oinaion=Unye, Polemonion=Boleman, Iasonion Akron=Yasun Burunu, Zephyrios=Zefre Liman, and so on. The dissolving place names, though miraculously preserved so far, reflect the vanishing past, like the Byzantine church used as a chicken coop in Platana, or the famous monastery of Soumela, founded in the 10th century, abandoned in 1923, reduced to a haunt of smugglers, burnt in 1930.

The photographic journey continued over the mountains from Trebizond to the heart of old Armenia, to Lake Van. The incredible castles and poignant ruins have a new significance for anyone trying to follow the events in the neighboring Soviet Socialist Republics. The descriptions of Xenophon and his soldiers crossing the plain in winter, the Armenian palace-episcopate on the island of Achtamar in Lake Van, and the sufferings of the Pontian refugees who fled to Kars after 1918, the fabulous photographs of Mount Ararat and indeed the photographs in general make one long to visit the area. The text leaves one bristling with question marks. This book could have been improved by a more scholarly approach and more rigorous discipline in its organization, but it is absolutely fascinating and well worth reading nonetheless. I haven’t seen the English edition yet (which is due out by the first of December), but it will certainly be a “must” for Christmas coffee tables.