Music and racing are two activities that fail to leap to mind when considering land tortoises. But in antiquity, the unassuming tortoise won races against the hare and the great warrior Achilles. And the most noble musical instrument of antiquity, the lyre, was fashioned from the carapace of the lowly turtle. (Technically, tortoise refers to the land creature as distinct from the aquatic turtle, although the words are often used interchangeably, as in this article.)

Remember Aesop’s fable, in which the tortoise, slow and steady, wins the race with the overconfident hare which dawdles on the way to the finish line? The philosopher Zeno of Elia (born about 490 BC) put a twist on the story when he pitted a tortoise against Swift-footed Achilles in a theoretical race. Because proud Achilles can run ten times as fast as the turtle, he gives the turtle a headstart of 100 yards. But, in Zeno’s famous paradox, Achilles will never win, because as he runs those first 100 yards the tortoise covers ten more, and while Achilles runs that ten the tortoise advances one more yard, and while Achilles runs that one yard, the tortoise moves forward one-tenth of a yard, and so on ad infinitum.

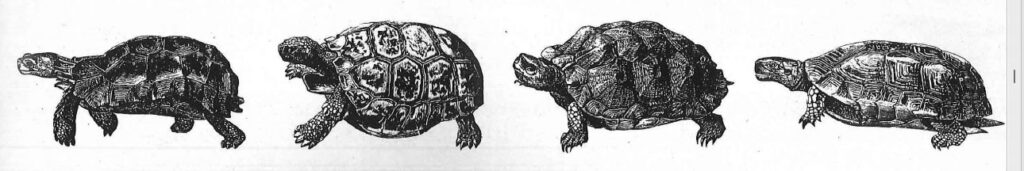

In real life, Aegean land tortoises plod slowly over fields, through the golden stubble under olive trees, and across the rocky hills and mountains of mainland Greece and some islands·I have often encountered them in isolated valleys and on high ridges, laboriously making their way over outcroppings and through thorny underbrush. In the hot, arid summer, you can hear them approaching through the crackling dry weeds. Once I saw two turtles bashing one another like miniature tanks among the windflowers and poppies. I assumed they were disputing territory. Three species of land tortoises inhabit Greece, Testudo graeca, T. hermanni, and T. marginata. The last are unique to the mountaintops of certain Cycladic Islands: their ancestors were left high and dry when land bridges connecting Asia Minor and Greece disappeared during the last ice age. The distribution of these terrestrial turtles helps scientists determine the history of changes in sea level and land masses in the Aegean. T. graeca tortoises, for example, live on Cos, Thasos, Samothrace, Limnos and Samos, where they were stranded, along with the lesser mole-rat and some lizard species, when the last glaciers melted. The T. hermanni species prefers lower altitudes, such as on Euboea. On Patmos, Kythira and Chios, land tortoises are quite rare. And in antiquity, Aegina was famous for minting silver coins with the image of a turtle, but no tortoises have been sighted there since the last century. Naxos, Kythira and Skyros are home to the T. marginata; they are also found in the mountains of the Peloponnese and south of Mt Olympus.

In antiquity the tortoises of Mt Parthenion (near Tripolis in the Peloponnese) were sacred to Pan. This is where Pan promised the powerful runner Pheidippides that he would help the Athenians beat back the Persians at Marathon in 490 BC. Pheidippides was dispatched to Sparta to ask for help when the Persians landed: he ran about 150 miles in two days. After the Greek victory, races were held in Pan’s honor. Perhaps the tortoise was honored as well, in memory of its own improbable racing victories. Or perhaps the Pan’s tortoise mascot was chosen in the same ironic spirit that led a basketball team in California to call themselves the “Slugs”.

In the second century AD, the travel writer Pausanias visited the cave where Pan made his promise. He wrote that the area had lots of tortoises, “which are excellent for making lyres, but the people are terrified to kill them and forbid strangers to take them, for they believe the creatures are protected by Pan,” a god known as the avenger of cruelty to animals.

Admiration for the tortoise’s determination and simple, effective means of self-defense seems universal. The Romans named their defensive military maneuvers the testudo (Latin for tortoise) in which soldiers advanced slowly under a “shell” of interlocking shields. A folklorist travelling in Macedonia around 1900 heard that it was considered very lucky to come across a tortoise, and very bad karma to kill one. Moreover, anyone who found a tortoise upside down had a duty to help it – and anyone malicious enough to flip one onto its back committed a dire sin. The villagers said that the very sight of a turtle upside down is “an insult to the Deity!”

Oddly enough, the Original Tortoise once insulted Zeus. According to an ancient tale, Zeus invited all the animals to his wedding. Only the turtle stayed home and Zeus demanded to know why. The turtle replied that his house was dear to him to leave it even for a grand party. Miffed, Zeus decreed that such a homebody should have to carry his precious home with him ever after.

Eagles were companions of Zeus, and so no friends of tortoises. Ancient naturalists told how eagles would seize tortoises and drop them on rocks to smash the shell and eat the flesh. The playwright of tragedy, Aeschylus, died in 456 BC, killed instantly when an eagle dropped a tortoise on his bald head, mistaken for a rock. This shocking accident must have reminded many Greeks of the tragic fable about the turtle who learned to fly.

Once a turtle told the swallows, “Would that I too had wings to fly!”

An eagle overheard this exchange and said, “How much would you give if I enable you to rise effortlessly high up in the sky?”

The gullible turtle answered, ‘Td give all the riches of the Orient!”

“You’re on,” said the eagle, “I’ll teach you to fly!” He carried the turtle aloft upside down until they reached the clouds. Then the cruel eagle dropped the tortoises on a mountainside, dashing his hard shell to smithereens.

As he fell, the turtle was heartily sorry: “What possessed me to wish for clouds or wings when even on the ground I could not move with ease?”

Although tortoises are certainly easy for humans to catch and kill, there is not much evidence that anyone ate land turtles in classical times. But they were highly esteemed for medical uses. Pliny, who wrote on natural history in the first century AD, listed 66 remedies based on tortoises. A modern excavation at Nichoria revealed that in Byzantine times, when food was very scarce in parts of Greece, small tortoises were cooked for supper.

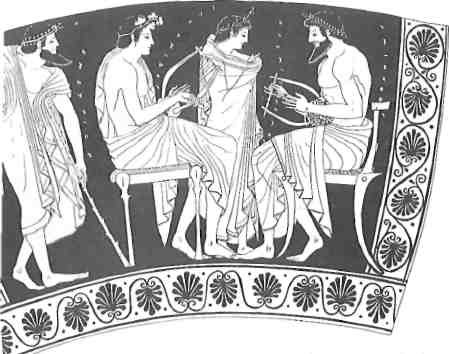

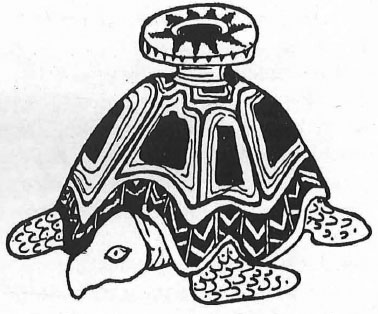

The shells of turtles were once in great demand for making musical instruments. An ancient riddle asks, “What lifeless thing can produce a beautiful living sound?” Answer: a lyre made of a tortoise shell. The legend of the origin of the lyre goes like this. Hermes, as a boy living near his birth-place in a cave on Mt Kyllene, slaughtered some oxen owned by his brother Apollo. Then he saw a tortoise by the cave. He killed it too, stretched some ox-hide over the concave carapace, and fixed seven ox-gut strings across the soundbox. By inventing the first lyre (called a chelys or turtle), Hermes was said by Homer to have “created endless delight because it was he who first made a minstrel of a turtle.” The boy

assuaged Apollo’s anger about the dead oxen by plucking a tune on this simple instrument.

The traditional lyre was made of a turtle shell with two horns of wild goat extending as parallel arms from the soundbox. Sinews or ox-gut of various thicknesses were strung from the cross-bar between the horns to the shell. The instrument produced music described as “noble, serene, and virile”. In the right hands, a lyre was liable to make stones dance, rivers stop and wild animals tame.

Hermes taught Orpheus to play the lyre so sweetly that he could soothe even the gods of the underworld with his songs. When Orpheus was killed by maenads, his lyre fell in the sea and washed up on Lesbos, at Antissa. A fisherman brought the instrument to Terpander. This poet-composer of the sixth century BC is known as the founder of classical Greek music; he won many contests in Sparta with his com-positions for the chelys. Another famous musician, Arion, played the lyre to save his life. He had been captured by pirates on the way home from a concert tour. Dolphins gathered around the boat when he played on deck – Arion dove overboard and was borne safely ashore by his audience.

Orpheus had taught the poet Linus to play the lyre, and his mournful songs became famous enough to be called “linuses”. Like Aeschylus, Linus was to discover that when poet’s skull meets turtle shell, it’s Turtles 2, Poets 0. Hercules took music lessons as a boy from old Linus, and when he was reprimanded for his poor playing, he bashed his master over the head with his heavy tortoise-shell lyre, killing him.

Plodding so patiently over thee landscape in search of morsels and dewdrops, this low-profile homebody, master of passive self-defense, seems utterly removed from the kinds of ruck-us we’ve heard associated with its name in antiquity, not to mention lyrical music.

And yet… Picture zoologist George E. Watson of the Peabody Museum, binoculars around his neck, notebooks in hand, stepping through scrubby thickets of thorny burnet on the island of Cos. It’s a fine day in May 1961. He cocks his ear, startled by a peculiar knocking sound. Ten metres away in a little clearing he spots a “female Testudo graeca being pursued by an ardent male T. graeca.” Rivetted by the spectacle, Professor Watson sits down and observes the tryst through his eight-power binoculars, scribbling furious notes. The naturalist Aelian remarked in the second century AD that the tortoise was “a most lustful creature”, and speculated that “since the males couldn’t sing they must have charmed the females by means of a herb.” But Watson’s monograph, “Notes on Copulation and Distribution of Aegean Land Tortoises” is the first scientific eyewitness account of the courtship of the Greek species. Hermes may have been the first to make a lifeless turtle-shell sing but it was Watson who told the world about the mating call and lively courting dance of the lovesick Greek tortoise.

The rhythmic knocking sound that Watson heard was the suitor bumping his sweetheart’s carapace with his own to get her attention. His crashing and bashing kept up for nearly half an hour: she kept on moving up the hill in the underbrush, pausing flirtatiously and starting forward again. He was thrown off balance, tumbled down the incline and landed upside down. Watson saw that the turtle finally righted himself and “recommenced his pursuit and bumping.” Again and again he rolled downhill, got right side up and began his bumping anew.

The tortoise began to sing! Watson knew of some earlier reports of turtle mating calls in other parts of the world, but all previous studies concerned captive turtles and no one had described any vocalizations by native Greek species. A German had once maintained that the European land turtle’s cry was “very like a cat’s miaow”. Leakey claimed that a tortoise in a zoo in Uganda gave a “loud husky cry” when courting. A pet South American tortoise bobbed his head and emitted a sound “like a mother hen teaching her chicks to scratch for food,” while another turtle native to an island in the Indian Ocean “gave a deep trumpeting call.” The two species of giant Galapagos tortoises have rather different courting styles. One is quite taciturn -he skips the shell-bumping ritual altogether and managed to “roar with his mouth closed”; the other sways his head, bumps a bit, and then opens his mouth wide to give a “light and gasping call”.

The mating call of the wild tortoises of Cos was “audible for at least 20 metres.” Watson saw him open his mouth and heard a “high nasal whine, somewhat resembling a complaining puppy’s voice.” He also noted that the song was short, lasting about half a minute.

No ancient author ever mentioned the call of the live turtle, preferring to dwell on the beauty of the music produced by the hollow tortoise-shell lyre. But thanks to Watson of the Peabody Museum, whenever I walk through hillocks of oregano and thorny burnet, I listen for crashing carapaces in the underbrush and a live version of the wild tortoise song.

This article is dedicated to a young Greek Tortoise named Arete who flew to California in the pocket of her friend Amanda and who now lives happily browsing on tiny wild strawberries and purple lobelia blossoms in Santa Barbara.