At the southwest corner of the Greek mainland there is a scattering of little islands around a marshy coast. To the south and east lies the Gulf of Patras which connects with the Gulf of Corinth to separate the mainland from the Peloponnese. To the north and west are more islands and then the open sea. Cutting diagonally across the corner is the road from Mesolonghi to the fishing port of Astakos, from which daily ferries take visitors to beautiful Ithaca and Cephalonia. Between the road and the sea is a fertile plain irrigated by the longest river in Greece, the Acheloos, which winds down from the mountains of Epirus. The chief town of the area is the agricultural center of Katohi, served by frequent local buses from Mesolonghi, where grimy farmers sit in the shade and watch the world go by.

Ten minutes’ drive beyond Katohi along the dead flat plain brings you to an outcrop of low hills. As you approach them, you notice that the largest of the hills is ringed by a thick stone wall. Here and there a tower or a gateway is visible through the bamboo along the roadside. The local name for this place is ‘Trikardokastro’ (or ‘Trikardo’ for short), which means ‘castle with three hearts’. In the very remote past, the city here was called Erisichis, but the name by which it was known to Thucydides and Polybius, and the onewith which it is marked on maps and signposts, is Oiniades.

The plain around Oiniades was, in ancient times, largely under water. The city overlooked a series of shallow lakes, and the waters of the largest, Lake Melita (named after a nymph), lapped around the city just below its walls. Lake Melita opened onto the Acheloos, and the island city of Oiniades traded down the river to the sea. The island was at one time one of the group which is still clustered around the present-day mouth of the river, some ten kilometres downstream.

These islands, the Ekhinades, including Oiniades, or Erisichis, were in mythology the daughters of the river. Ovid tells a story of Theseus visiting Acheloos, personified as a river god, in his palace. Acheloos tells him that all the Ekhinades were once naiads, but that they were turned to stone as a punishment for forgetfulness. Coins found at Oiniades show Zeus crowned with laurel on the obverse, and Ache-loos on the reverse. It is supposed that the people of Oiniades worshipped the river god upon whom their prosperity depended. He is pictured as a horned man, from whose beard water drips. We come across him again in another myth, which explains how the city acquired the name: Oiniades.

In the nearby city of Kalydon, there once ruled a king called Oeneus. This fortunate man was the first mortal to cultivate Dionysos’ magic fruit, and his vineyards were the toast of Greece. (The anthropologically-minded might find in this myth a folk-memory of the spread of the orgiastic wine-cult to western Greece, but let us suspend our disbelief…) Oeneus had a beautiful daughter called Deianera, and the river god Acheloos conceived a passion for her. His dreams of conjugal bliss, however, were thwarted by a chance visit to Kalydon by the mighty Heracles. This hero decided that he, too, desired the fair Deianera, and (inevitably) single combat seemed the only way to resolve the tender conflict.

Acheloos, being a god, had magical powers, and as Heracles tried to subdue him, he changed from a horned man to a spotted snake, to a charging bull, but Heracles held on grimly, and Acheloos was forced to yield. Heracles contemp-tuously wrenched off one of his horns, and Acheloos slunk away, defeated. The Ekhinades islands were spoils of victory, and Heracles presented the island of Erisichis to his new father-in-law, Oeneus, and it became known as Oiniades’. (The anthropological voice might once again intrude, to suggest that this myth might record the deflection of the river and the drainage of the marsh to allow its cultivation. Elements of the story, such as the demi-god hero and the shape-changing horned man, are prob-ably survivals from an earlier, pre-Olympian, religion).

Disregarding mythology, the city’s name seems to derive either from oinos – wine, or from oini – vineyard, and the fact that the name Oiniades is plural suggests, etymologically, that the city took its name from the surrounding fields, and that the name could be rendered into English as City of Vineyards.

The river formed a natural boundary between the territories of two peoples: the Aetolians and the Akarnanians. During the Greek Dark Ages, following the collapse of Mycenaean civilization, hundreds of independent city states arose all over Greece. In western Greece, those cities peopled by Aetolians gradually began to cooperate and trade with each other. The Akarnanian cities, including Oiniades, were slower to adopt this radical new system of social organization, and the Akarnanians were thought of as primitives and barbarians in the rest of Greece.

Nevertheless, the natural advantages of the site of Oiniades, with its sheltered sea port and fertile fields, and the existence of the almost unassailable Akarnanian stronghold of Stratos further upstream to protect the river, gradually brought prosperity to the Akarnanians. In time, the Aetolian cities, unified as the Aetolian League, would cast greedy eyes on the Akarnanian trade route (although they were probably more interested in it strategic value), but a trading liaison with the great city of Corinth brought a steady flow of ships up the Acheloos to the port of Oiniades during Corinth’s hold over the ‘Western Sea’ routes (800-600 BC).

The city’s walls date from the close of this association: did they realize they would be needing walls to defend themselves? Perhaps the walls were instead a gesture of wealth and power. In any event, in the sixth century BC over seven kilometres of walls were built, completely encircling the city. Although some parts of the walls, and isolated stones elsewhere in the city, seem to date from an earlier time, it is with these walls that the archaeological record really begins.

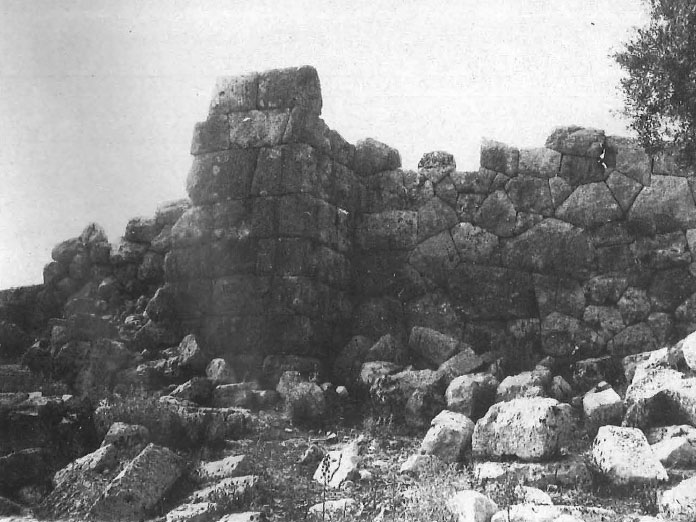

The sixth century walls are built in the Cyclopean Polygonal style; polygonal because the walls are built from irregularly-shaped boulders which are flattened only where they touch, so that the outside of the wall is composed of natural, rough boulders which are joined (without mortar of any kind) by straight edges, so as to form irregular polygons; and Cyclopean because the similar, although much older, walls at Mycenae were, according to legend, built by the Cyclops.

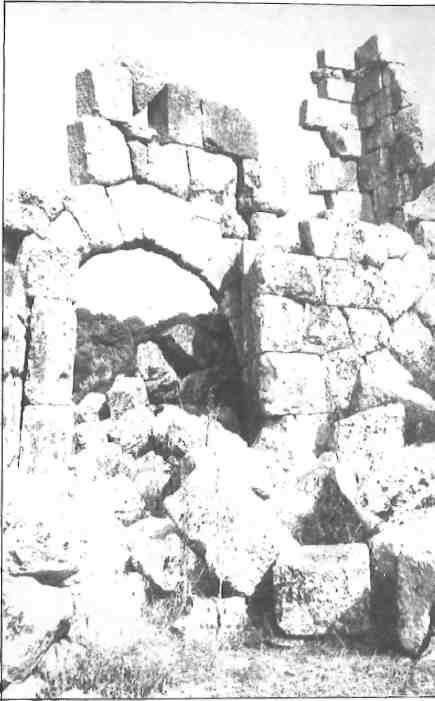

The walls would have been topped by further mud-brick defences, but these have long disappeared. Only the stones remain, snaking around the hillside; fallen in some places, and displaced by growing trees in others, but on the whole in very good condition; in many places, indeed, still perfectly straight and true. There are two large gateways in the walls and 12 smaller ones. These have attracted considerable interest from archaeologists. The polygonal style of masonry is, as the ruins of Mycenae (c 1300 BC) show, of great antiquity as a building technique. It was also used by the Maya and other Central American peoples, and is a very robust way of building walls, as the condition of the remains shows.

It is remarkable that at Oiniades the gates which pierce the walls are arched. This is the only place where these two architectural elements are to be found in the same structure. In fact, each gate is different. Some are arched, some have simple lintels, and some are (or were) vaulted, somewhat in the manner of tholos tombs. It is not clear why people with this repertoire of building skills should have decided to use such a cumbersome and labor-intensive method as polygonal, rubble-filled walls for their fortifications. No doubt they had their reasons.

The walls follow the shape of the hillside as it forms a long narrow indentation: this was the natural harbor of the island. There is a concentration of fortifications overlooking it. On second glance, it appears that many of these fortifications, and particularly the large square tower that dominates the skyline, were not built in polygonal masonry, but in regular courses of dressed stone. To see what these are doing there, we must catch up on a little more history.

In the fifth century BC, the organization of the various federations of Greek city states improved steadily, and warfare acquired a new strategic element as a result. For centuries, the aim of warfare had been principally to sack cities and carry away treasure, killing the men and choosing sex slaves from among the women. The aim of a city’s defenses, therefore, was to deter or prevent such an attack.

As trade replaced plunder as the normal means of raising revenue, and as cities banded together to form larger economic and military units, the defense of each city was no longer simply a question of protecting life and limb in one little enclave: such considerations as supply lines and control of waterways began to give cities an importance that stretched beyond their own horizons.

Athens took the lead in the military annexation of territory, and increasingly begrudged Corinth the power and wealth its sea trade brought.

Oiniades fell in 455 BC to Messenians exiled in Nafpaktos and, perhaps thinking that this proved the city could be taken, the Athenians decided to seize it. Two years later Pericles himself assaulted the city with 100 ships and 1000 Athenian foot soldiers. The city resisted this seige but, in the end, having been caught up in the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) joined the Athenian alliance in c 425 BC.

Time went on, and the nearby Aetolians, now a rich and powerful people, took the city from the Athenians, beginning a period of 150 years of fighting between the Aetolians and the Akarnanians. Oiniades changed hands several times, and both sides suffered terrible losses. In the third century BC, the Akarnanians retreated, making their new headwquarters at Lefkada, and leaving Oiniades in the hands of the Aetolian League. When Philip V of Macedon attacked the Aetolians in the War of the Leagues (219-217 B.C.) he found himself in possession of Oiniades, and decided to improve the city’s defenses. It is from this time that the more recent structures at Oiniades date.

This was a period of innovation in warfare. Philip himself was eventually defeated and the aspirations of Macedonia crushed by a Roman elephant charge at Cynoscephalae in Thessaly.

At Oiniades, the work of Philip’s engineers anticipates that of the builders of medieval European castles. Whereas the older defenses simply presented attackers with a large blank wall, Philip built a series of towers and angles, so that the defenders could overlook important weak points, such as the large gateways and the port. One of the most striking features of the site is Philip’s military dock, cut into the rock to allow ships to berth right up against the city walls. The whole dock is today high and dry, and the huge grooved stonework rises out of the plain, dwarfing the huts of the local farmers.

The ‘Three Hearts’ of the modern name refer to the three high places that Philip chose to fortify most heavily: the front gate and dock complex, a guard tower at the other end of the city, which commands a breathtaking view across the plain to the sea, and the ancient acropolis of the city. Here, too, Philip’s coursed masonry is superimposed on older polygonal work. Oddly, the older walls have generally lasted better, and the ‘improvements’ are mostly fallen and cracked.

Perhaps realizing that the original walls were no longer defensible, Philip continued his fortifications inside the city, seemingly trying to isolate a stronger section of the city. The chief ‘heart’ of Oiniades, however, remained the acropolis.

Walking up from the port area, passing the theatre (of which more later) and heading up to the acropolis, the visitor finds himself in a landscape of groves of oak and olive trees. The air is scented with wild herbs, and the woods are alive with butterflies and grasshoppers. The ground rises and falls in little hills and valleys, sometimes densely covered with thorn bushes and other scrub, sometimes opening out into bare earth clearings studded with rocks. Goats roam over the hills, and lizards and tortoises lurk under fallen stones.

Every now and again you come across a section of Philip’s walls, nestling in a hollow in the ground and covered with moss and creepers. As you approach the acropolis, the fallen stones get thicker on the ground, as do the thousands and thousands of pieces of terra cotta that are the remains of brick-work, decoration and storage jars. Climbing up the wall onto the acropolis proper, you suddenly rise above the tree line, and the horizon opens out for miles and miles in every direction.

The acropolis, last refuge in case of attack, was built on a natural spur of rock, with a drop over the side, and perching on this you gaze out at a line of distant mountains and islands stretching all the way from the Peloponnese up past the Ionian islands to Epirus, fading away towards Albania to the north. At your feet, the big, fat river winds across the plain to the sea.

Oiniades is large enough to require days of exploration. Apart from the approach road and the theatre, which are carefully kept up, the only recent work on the site has been to burn off some of the scrub, and the only other human beings you are likely to find in the woods are the goatherds you sometimes hear calling their animals. As the city was built of the same local stone which juts out of the ground of its own accord, it’s often difficult to tell until you are up to it whether a particular group of stones is natural or man-made.

Apart from the fortifications and the theatre, there are a number of other places in the city with ancient remains. A curiosity, just outside the walls of the acropolis, is a stone seat or throne, which you can sit on and have just about as good an idea as anybody else as to who it was originally made for. The foundations remain of a group of houses, and of stone cisterns to collect rainwater for drinking, an essential feature in this arid crountry. There are remains of a Greek bath-house, the original of the great Roman bath-houses, with a succession of rooms which were kept at different temperatures. Crossing the mouth of the ancient port, how home to families of pigs which wallow in pools of mud there, you come to a gate with a small temple just inside: this is filled with bushes, and seems to be still mostly buried.

The religion of the Akarnanians is a mystery, beyond the numismatic evidence in favor of Zeus and Acheloos, and the temple does nothing to clear up the mystery. It used to be called the Temple of Apollo, but for no very good reason, as the only evidence of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated is a fragment of statue found by the American archaeologist, Powell: the fragment represents the toes of one divine foot.

This and other mysteries could soon be resolved. Following the excavation of the theatre in 1986, by an international team, the Town Council of Katohi is this year coordinating a joint excavation by the Universities of Augsburg (West Germany) and Athens, covering the rest of the site.

Most visitors to Oiniades today are attracted by the theatre, and in particular by the splendid Festival of Ancient Theatre which has been presented there since 1986.

After the theatre was excavated in 1986, an international symposium on ancient drama was held, under the auspices of the International Workshop and Study Centre of Ancient Drama. An integral part of the symposium was the rehearsal and performance of a Japanese Kyogen play directed by Andrew Tsubaki, and of Sophocles’y4fl£/gt>ne directed by James J. Christy and Heinz-Uwe Hause. The occasion was shared by the Greek regional company of Agrinion, which performed Aristophanes’ Achamians. After 2000 years, the theatre was again in use.

Following the success of these first performances, the Town Council of Katohi has organized an annual festival. Each year, in July or August, different Greek companies present classical drama, in modern Greek translation. Each performance draws about 3000 spectators, mostly Greeks, but also a few Italians and other foreigners. This year the festival presented companies from Larissa and Veria, performing Sophocles’ Electra and Aristophanes’ Plutus and the private company of Kazakos-Karezis performing Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. Next June, an American group from the University of Kansas will visit Oiniades for a 42-day study period, during which they will rehearse and then perform Euripides’ Hippolytus.

The theatre itself has a wonderful natural setting, marred slightly by the two-metre wire fence which has been erected around it.

Thirty rows of seats were cut into the rock of a natural bowl in a hillside, and are rather prettily worn away in a channel down the middle where a mountain stream once ran. The lower seats are not eroded at all, having only been exposed again in 1986, and one can read inscriptions – the names of freed slaves – it having been a custom for freed slaves to hire stonemasons to commemorate their liberation.

The stage is a circle of beaten earth with a channel around it – originally for drainage – separating it from the audience. At the rear of the stage is a pile of stones with the stumps of a few pillars: this was once a rather elaborate building on two levels which also offered a gallery from which gods could look down on the action on the stage below. The theatre buildings, like the rest of the site, are in two layers: first there is a fourth century BC original, built when the city was under the influence of Athens, and then Hellenistic additions. It is speculated that these, like the fortifications, were the work of Philip V, but there is no evidence for or against this conjecture.

Since little but the stage and auditorium is left, it is the site’s natural beauty which dominates: the wooded hillside, the plain, the mountains in the distance; the quiet clanging of goat bells somewhere.

Immediately Philip had finished his fortifications, Oiniades was invaded again although, to be fair, it did hold out a bit longer than other nearby cities. The Akarnanians took their city back, but while the Greeks were still arguing among themselves, a new world order was being established: the Romans were coming. When they arrived a few years later, they handed Oiniades back to the Aetolian League, but the Greek alliances soon lost their military significance, being little more than useful administrative divisions for the Roman overlords. Oiniades went back to farming, trade, and presumably the theatre, and life must have been rather quiet, the whole region having now been ravaged by generations of warfare.

On 2 September, 31 BC, Antony and Cleopatra watched as the Roman Emperor Augustus’ commander, Agrippa, defeated their fleet at the Battle of Actium (near modern Preveza). This foiled their scheme to invade Italy, and Augustus was so pleased that he decided to build a ‘Victory City’, Nikopolis, to commemorate the battle. He peopled his new city with the population of the surrounding countryside, and Oiniades, in common with the other neighboring city states, was suddenly depopulated and abandoned. Over the centuries, most of the buildings fell down or were pushed down by trees. Rainwater piled earth up against walls and towers. The river changed its course, and nobody had any reason to visit Oiniades any more. Even its name was forgotten.

Some time or other the locals began to call the place ‘Trikardokastro’, the thorn bushes grew, and the stream did its worst with the seats in the theatre. Every now and again a bit of wall fell over.

In 1436, the site was visited by the Italian Cyriac of Ancona, who called it Tricardon’. The French traveller Pouqueville, in his Voyages dans la Grece (Paris, 1826) quotes another, anonymous, early visitor, who wrote: “In Epirus prope Acheloi fluvii ostia est civitas magna et vetustissima quam incolae Tricardon vocant, moenibus undique lapidus magnis atque mirabili architectura munitam.” An Athenian citizen, one Meletios (1661-1714), who knew his Thucydides, identified ‘Trikardo’ as ancient Oiniades and, slowly, the city began to be rediscovered.

Travelling in Greece was a dangerous business during the Turkish occupation, but in the 19th century there was a trickle of visitors who wrote about the city: the Englishmen Leake (1809), Urquhart (1839) and Muse (1838), the Frenchman Heuzey (1856), and the German Schillbach (1857).

Eventually, in 1900-1901, the site was systematically explored by the American School. They cleared away some of the undergrowth, dug out the theatre, reassembled some masonry and went away again.

Now that the undergrowth has grown back again, once you get away from the road and the theatre with its fence, the city must look pretty much the same today as it did to those 19th century visitors. Colonel Leake, who described the site in Travels in Northern Greece in 1835 might be describing Oiniades today: The ruins and woods of Trikardho are singularly picturesque.’