For centuries custom obliged women to cover their heads when appearing in public. Whatever modesty required, coquettisness may have reinforced, and the swathed figures of ancient Tanagra terra Cotta figurines are among the most stylish renderings of the female figure.

The characteristic headgear of Byzantine times and its ornamentation naturally evolved into the costume of modern Greece where scarves became an accessory of great beauty and unlimited variation. Among these, the embroidered, woven, but almost always printed ones played, and indeed still play, a fundamental role both for practical and decorative purposes…

It was during a very hot Saturday summer morning that I visited the factory of Mr Dimitris Oikonomopoulos founded by his family a century ago. He is the last craftsman in the tradition of the printed scarf and he adheres to a heritage in a way that he calls ‘adamant’. This factory lies in the Athens neighborhood of Metaxourgeion where the streets and houses and even the atmosphere have changed little since the turn of the century.

Behind the heavy sliding metal door of this factory, blackened by labor and time, there exists’ another world softened by memories and the genial smile of the proprietor. Pulling aside a corner of a huge drapery of beautifully printed Byzantine design hanging from the ceiling, he led me into a spacious, dark and damp room. Large pieces of printed textile hanging all around gave the impression of a theatre set designed by an imaginative, contemporary director. In another room farther on, metre after metre of material was slung over an enormous table, and a cat dozed in a corner.

In his office where everything – the furniture, pictures and posters-looks as if it hadn’t been touched in several decades, Mr Oikonomopoulos lit a cigarette and in a low and deliberate voice recalled a life full of memories and rich experiences against the background of a craft which his family has been professionally active in since the last century on the island of Syros.

The tradition of printed scarves that decorate women’s – and sometimes men’s – national costumes can, of course, be traced much further back, at least to the 17th century at the important workshops in Constantinople and Smyrna.

The early history of the craft is described in a pamphlet called “Painted and Printed Scarves from the Workshops of the Bosphorus” by Soula Bozi who was born in Constantinople. Herself a collector of old printed scarves and an expert on the subject, she traces the development of the craft to Asia Minor and particularly to the region of Pontos which was inhabited by Greeks and Armenians. Some of these craftsmen moved to Constantinople and formed guilds, and the craft flourished in the famous Bosphorus workshops from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

Immediately after the War of Independence, John Capodistria, president of the first Greek provisional government, encouraged craftsmen from Turkey to settle in the new nation, especially on Hydra. Production was small, however, but the demand for printed scarves so great that scarves were imported from Switzerland, earning them the name “souitseras”. From Hydra the craft spread to the then flourishing island of Syros where production was mainly of the Costantinople, or kalemkeria, type from the Turkish work “kalemi”, or “pencil”, and that of Smyrna, or basmades, from the Turkish word for “printing”.

In the first type of scarf, the artisan works like a painter, doing most of the work with a brush and painting the design directly onto the fabric. With the Smyrna type the printing is done with a wooden block on which the design is chiselled. Carved on lime wood, they are themselves often authentic little works of art. As many blocks were used as there were colors and women often specialized in a single color. A mixed type also exists, combining painting with block printing.

One of the first print scarf workshops on Syros was the House of Oikonomopoulos and Velissaropoulos. In 1907 Iraklis Oikonomopoulos came to Athens to visit relatives and during a ride in a carriage, his son Dimitris related to me, “He came to this exact spot and noted that there were stables for horses here. This meant that there had to be a dependable well in the vicinity for watering them.”

Abundant water is essential to the manufacturing of scarves because the colors on the textiles after printing must be well rinsed before being spread out to dry. Seawater is best, however, giving an especially vivid look and making the colors fast.

Pointing to an opening in the floor of the largest room, Dimitris Oikonomopoulos expained, “This well draws water from the underground aqueduct of Hadrian. For 80 years we have been pumping out water for our daily needs and though the depth is only four metres it is always full again the next morning.”

The printed scarf business spread to Patras, Volos and elsewhere, with workshops almost always near the sea. At first, textiles were brought from England and the best qualities are still imported.

From his archives, he draws a business card engraved with a whiskered gentleman and bearing the legend, “J.N. Boothman, Founder. A.D. 1870. Bleachers.”

Over all these years, the Oikonomopoulos business has had its ups and downs. Today, it is the only large workshop left of its kind. Dimitris took over the business when his father died in 1946 and is proud to say that he has maintained the high quality of work and preserved the secrets of coloring material. He remembers the admiration and surprise of the Germans when two pieces of textile, both in black designs, one using Bayer Chemical paint and the other traditional Oikonomopoulos paint, were plunged into vats of water and chlorine. “Within a hour,” Dimitris said, “the Bayer paint had turned brown, but ours had kept its vivid black color, and the water was clear even though the textile had nearly dissolved.”

During World War II the workshop produced huge quantities of gauze for Army bandages. Then with the occupation, the workshop closed, but no employee was laid off and in spite of starvation around, everyone continued receiving wages.

Bombardment damaged the factory and it was hard work after the war getting business moving again. Prizes provided needed publicity. In 1949 the Piraeus Fair awarded him a prize for “outstanding products of headgear”. The following year he got a similar prize at the Thessaloniki International Fair and in 1956 a third at the International Fair at Damascus.

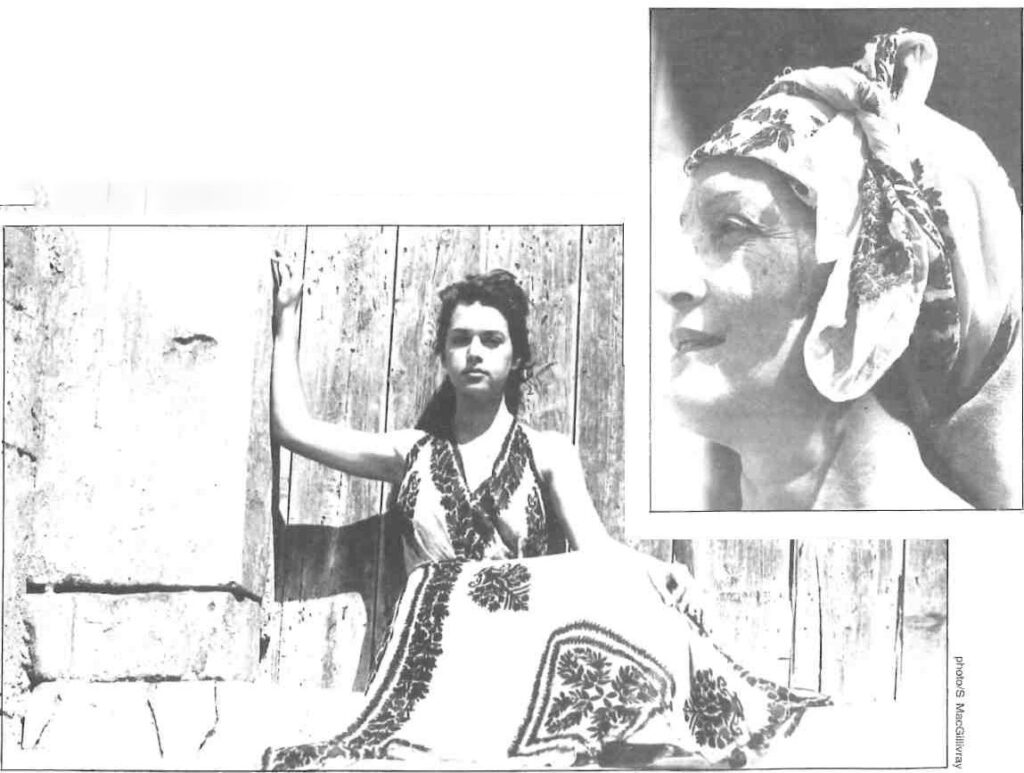

In the 1970s efforts were made to adapt scarves for wider purposes and export them. A campaign promoting dress fashions utilizing printed scarves was launched with the help of the Organization of Greek Handicrafts. A well-known fashion designer of Greek origin, Theoni Aldridge, wrote in an American magazine, “Greek peasant scarves magically converted into romantic and sophisticated dresses, knee-length or to the floor, are carefully pieced to form flowing, feminine garments with ruffled sleeves “and rolled belt.” Elie presented these scarves as glamorous accessories. Following the tradition of Greek country women in mourning, black scarves were now promoted as the really ‘in’ fashion.

(Right) This flowered Dodecanese scarf is worn with a bow on the side.

Italian and Scandinavian magazines advertised “il foulard-cappuccino” and described ways to wrap these scarves about the head. Dozia, a young Athenian designer, made her first appearance in a fashion show for the European market with an evening dress made from scarves in the Euboean design transferred onto dacron and polyester. At the same time the Greek Islands boutique in New York was selling these scarves to wear ‘babushka’ style, or like a turban, to throw over the shoulders, tie in a halter or use as a wrap-around skirt for beachwear.

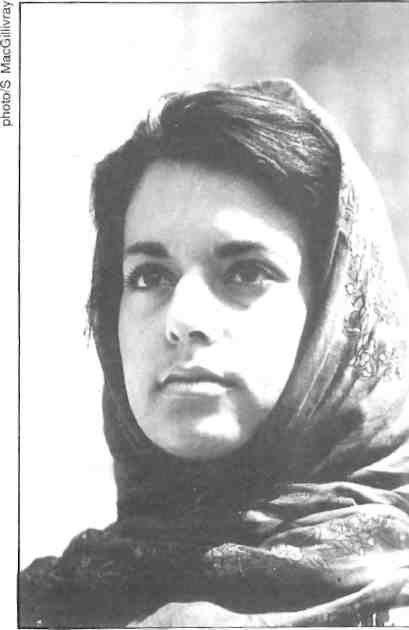

In traditional costume, the role of the scarf depends not only on a certain region, but the way women do their hair, their social status, whether the scarf is to be worn for every day or for a special occasion. Age and season are factors, too.

A scarf is a symbol as well. Often it is a gift from bride to fiance or from his mother to her. These usually are more elaborate with more sophisticated designs, hand-embroidered with gold thread, often edged with crocheted lace or a fringe. Traditionally the marriage scarf partly concealed the bride’s face, but after the ceremony it became a banner called the flambouro in the hands of the groom’s relatives and friends.

In the past, unmarried girls and women wore multicolored scarves; middle aged ones solid, duller shades of brown and blue. Finally, widows wore black scarves for the rest of their lives. An exception was the widowed mother of a bridegroom who always welcomed her daughter-in-law with a white scarf. The scarf was also a popular subject in folklore. The curse, “may you not put a scarf on your head” was a bitter one meaning “may you never marry”. In the Mani, where the mentality is as severe as the landscape, someone bound to a serious obligation is told: “Do it as if you had two scarves on your head.”

Scarves in legend had magical properties. They could lure back an unfaithful fiance. A Naiad who charmed a young man into her embrace and then deceived him could be won back if he stole her scarf. In this case she lost her power, married him, was obedient and faithful forever and ever unless, of course, she stole the scarf back.

There’s a whole literature about colors of scarves and their designs. Flowers are the commonest motif. They usually symbolize youth or dawn or spring or virtue. Some are decorated with birds or feathers; human figures much more rarely. Every area of Greece has its characteristic design. There are the gold and red scarves of Corfu, the multicolored wreaths from Megara, Euboean Psahna’s little blue flowers on a black ground, the magnificent leaves from Kymi, the outstanding black and red scarves of Volos. Oikonomopoulos has a collection of 200.

Some scarves are of silk. They are printed in a technique similar to Indian ikat which has evolved into our day as tie-dye. Most of the designs used to be imported, some from the nearby Balkans; others from as far away as Spain and Japan.

Block printing has become too laborious and costly for the Oikonomopoulos workshop. Production has turned to the roller and the screen.

A little shop across from the Metropolitan cathedral of Athens is owned by young Nikos Birlirakis who has been selling Oikonomopoulos scarves since his father’s day. He is forthright in his admiration: “Mr Dimitris is the top mandilas (or scarf maker) of Greece.” Nikos designs his own styles, too, and competes with the Italian and French. He aims at the younger generation.

“Punks and kamikaze motorcycle riders love these scarves, in smaller sizes, which they wear around the neck.”

More backward-looking, Dimitris Oikonomopoulos is less optimistic. He finds it impossible to keep up the high standards of the past. He is disappointed by the little State aid he gets.

“We’ve spent countless hours and made exhaustive efforts to work on various designs and shades of color, but it hasn’t paid. We send our scarves out to the provinces, to organizations and various folklore groups. We export, too, but it is not enough.”

Clearly, a central problem is that the family-oriented social structure and the environment which created and propelled the business is dying out.

“Young men nowadays either don’t want to work hard, or they want to earn a lot of money right away,” Dimitris Oikonomopoulos grimly concludes. His decision is taken; the manufacturer will soon close down. In a way it is fitting that a tradition should come to end when a family venture fails, since the Greek tradition has always been such a family affair. Until social priorities again change, course, it seems unlikely that any tradition can survive except in a museum sort of way.