Two companion exhibitions now on show in Athens are promoting Greece’s bid to hold the Olympic Games here in 1996 on the centenary of their revival in modern times. Under the general title “Mind & Body”, the exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum is sub-headed ‘Athletic Contests in Ancient Greece’ and the one at the National Gallery (Pinakothiki) The Revival of the Olympic Idea 19th-20th Century.

Certainly the more impressive exhibition is the one being held in five refurbished galleries of the Museum on Patission Street. Though the great majority of some 230 works of ancient art are from its own collections, important pieces are on loan from the British Museum, the Louvre, the Berlin Antikenmuseum as well as from other museums in Greece. All the objects are roomily displayed and well lit, so that even works collected here from other parts of the museum which may be familiar to local visitors seem enhanced or transformed. There is plenty of well presented and informative printed material in Greek and English and the visual aids, such as touch-screen videos, are helpful. The labelling is clear and bilingual.

In its formal bid to hold the Olympic Games here, Greece hopes to stress their original character which emphasized the union of mind with physical prowess and to revive their role in a broader cultural context by presenting performances in music and poetry such as characterized the Pythian Games at Delphi, and holding conferences and seminars on contemporary thought. Philosophical teaching in ancient times, of course, was closely allied with athletic contests and we are reminded that the three oldest gymnasia in Athens – the Academy, the Lyceum and the Kynosarges – were the original venues of the three great philosophical schools; the Platonists, the Peripatetics and the Cynics.

This wide cultural view gives lively variety to an exhibition that might otherwise have been thematically monotone. As such, it allows a fine marble head of Pindar from the Louvre to stand next to a late Hellenic clay chest depicting a chariot race, and an Aristotle herm to be placed beside an amphora depicting a ball game – making it easy to imagine him interrupting a discourse and raising his himation to kick back a stray ball while ‘peripatizing’ around the palestra – a thing that surely must have happened often.

The blockbuster masterpieces may dominate the show – the Marathon Boy, the Mourning Athena stele, the so-called Leonidas Head, the Kritikos Boy, the Delos Diadoumenos, the Westmacott Athlete (from the B.M.) – but it is the many smaller, lesser-known or unknown pieces that draw closer attention.

A notable aspect of the exhibition is the attention that has been given to the variety of material. Often in looking at large collections of ancient Greek art one sometimes feels lost in a marble quarry or a ceramic forest. There is no such danger here in the midst of a well-planned diversity of gold, silver, bronze, stone and semi-precious stone, as well as marble and clay.

The first gallery opens with a delightful prologue to the Olympic Games, objects devoted mostly to Minoan bull-leaping and Mycenaean chariot-racing. Two clay vessels of bulls with acrobats wound around their horns are charming examples of early Second Millennium Cretan art. There is also the Chariot Krater from Nauplia and the Vaphio seal-stone of vividly lavender sardonyx, one of the most elegant small gems in the world. An archaic bronze statuette of a horse and rider from Dodona is worthy of the Han Dynasty.

Indeed, the whole collection of small bronzes by itself is breathtaking. The finest of these are from the Acropolis Museum and the four others that lie on the sites which ranked with Athens in prominence of their games: Nemea, Delphi, Isthmia and, of course, Olympia. The great bronze votives from the latter are well represented, though the less well-known ones from Delphi have enormous verve. A masterpiece in miniature is the figurine of an infant from Nemea thought to be Opheltes in whose memory the Nemean Games were founded. An inch-and-a-half high, the figure sits, one leg tucked under the other with his right hand raised, like the Christ-child’s, in benediction. Though itself only 17 centimeters high, the great archaic bronze head of Zeus found in his sanctuary in Olympia is one of the most majestic renderings of the Father of the gods.

The liveliest room is separated into sections; each devoted to the depiction of the individual events: foot-racing, discus, javelin, wrestling, boxing, chariot-racing and that sort of Gorgeous George free-for-all called the pankration in which even getting kneed in the groin doesn’t seem to have counted as a foul.

Luckily, it is known that women, banned elsewhere, themselves held races at Olympia under the patronage of Hera, and in honor of this the British Museum has sent over the superb Bronze Running Girl, a lovely moment of grace in this overwhelmingly male enclave. And as a further sop to impatient feminists, there is the famous Attic red-figure hydria of Sappho receiving an early version of the Femina Prize for Poetry.

The catalogue of the exhibition is sumptuous and exhaustive but should perhaps be purchased after one’s visit, since, weighing in at two kilos, it is as heavy as a regulation discus.

The exhibition at the National Gallery is a bit of a grab bag, as if the curators had gone down to the cellar and rummaged around for anything that would evoke some image of ‘mind’ or ‘body’ and set it around ephemeral mementos of the 1896 Olympiad. The result is a kind of helter-skelter social portrait of Athens more or less at the turn of the century, but at other times, too. As such, it’s lots of fun.

There are wonderful old photos of the Games with men in stiff colors, boiled shirt-fronts and top hats standing around in arenas of beaten earth and against landscapes devoid of trees. There are also theatrical posters, musical programs, commemorative stamps, entrance tickets, diplomas, foxed photos of actresses in tragic poses, foxed photos of actors in comic poses, medals, ribbons and postcards; all the curious contents of grand-mother’s trunk – or more precisely, in this case – great-grandmother’s.

If ‘mind’ is as variously represented as a watercolor of the Athens Academy done in the 1850s and a photo of poet Yiannis Ritsos receiving the Lenin Prize in 1979, the conception of ‘body’ is taken quite literally and almost any expanse of exposed flesh will pass. Luckily, women are an integral part of the modern Olympics, so at this exhibition a large number of female figures provide aesthetic refreshment lacking from that exclusively jock show at the Archaeological Museum. Even so, a Tsarouchis sailor in his skivvie shorts somewhat overstretches the Aristoltelian ideal mens sana in corpore sano.

If this exhibition suggests a certain untidiness, there are solid historical reasons for its being so. The Olympic ideal did not spring neatly and in full attire from the head of Baron de Coubertin as Athena from that of Zeus. There were many false starts which had been occurring for decades before that great day in 1896.

A very interesting fact which the catalogue points out is that most ideas for staging the revival of ancient games were intimately connected with the great industrial exhibitions of the second half of the 19th century. To the people of that period the perfection sought for in ancient Greek culture and epitomized in its athletic contests supported their belief in technological progress.

The 1851 London International Exhibition which pupped the Crystal Palace began a wave of competitive industrial fairs in the West which culminated in the gigantic Chicago International Fair of 1893 and the Paris Expositions Universelles of 1889 and 1900.

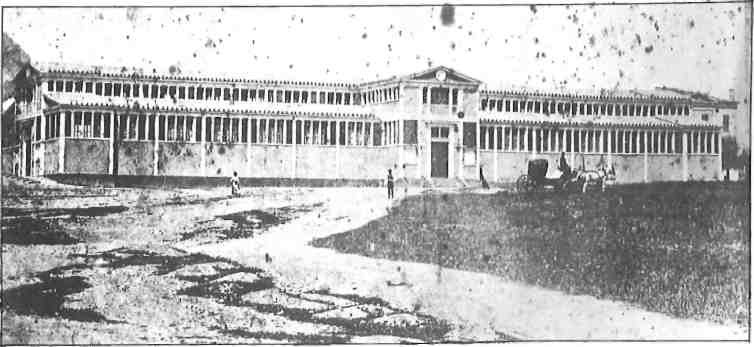

Though far more moderate, Athens, too, was bitten by the exhibition bug, and as early as 1856 the wealthy merchant Evanghelis Zappas had proposed to the government the creation of an institution which would promote Greek industry and agricultural products. Two years later the state decreed the foundation of the Olympia Expositions, granting land for their development which lay between the Royal Gardens and the Temple of Olympian Zeus. The proximity of the still-unexcavated Panathenaic Stadium was not lost on Zappas whose thirst to revive ancient athletic contests seems to have been from childhood an idee fixe as strong as his younger contemporary Heinrich Schliemann’s was to dig up the Homeric world.

The Olympia Exposition Hall, built in 1858 on the Amalias Avenue side of the present Zappeion Gardens, was one of the largest edifices in Athens. Raised as a temporary exposition structure like the later Eiffel Tower and the Trocadero, it did not achieve their more permanent immortality, though it did last 30 years, being pulled down only when the present Zappeion was completed in 1888.

For all of Zappas’ efforts, the athletic contests which accompanied the Olympia Exhibitions were only held three times. The venue chosen in 1859 in the Square of King Ludwig of Bavaria (now Kotzias Square in front of the Dimarcheion) was unfortunate. It allowed space for few spectators and the contests were a failure. The 1870 games were more successful because they took place on the site of the Panathenaic stadium, now unearthed though still unrestored, where wooden grandstands were temporarily set up.

The 1875 games were a disaster. Steeped in ancient history, the grand bourgeois members of the Organizing Committee, noticing how the ancient Olympics were from the start greatly favored by royal princes, banned the participation of the lower classes and allowed only “young gentlemen of suitable upbringing”. As such youths in 1875 Athens were few and far between, the bleachers were only occupied by members of their families.

Ironically, at the 1888 Olympia Exhibition when the Zappeion was finally opened and its original benefactor long since dead, no games took place at all. Like so many heroic undertakings in modern Greek history, tripped up by ensuing quarrels, achievement only came though foreign intervention, this time in the gentle and steadfast person of Baron Pierre de Coubertin.

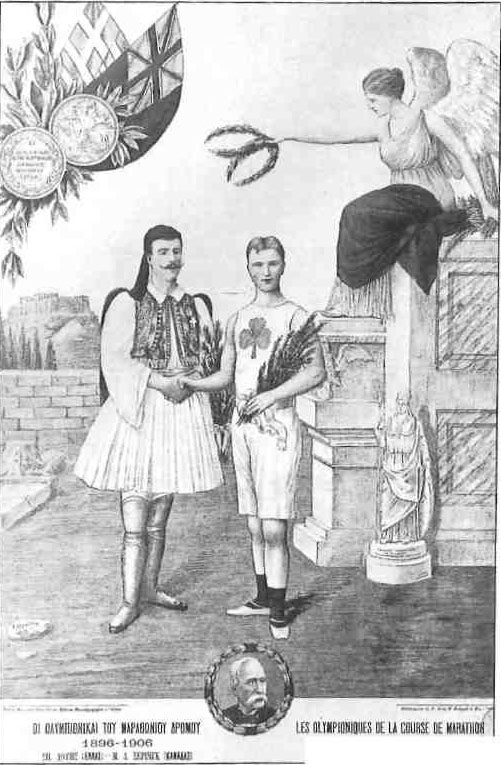

On the eve of victory, then, as ever, there was a mad last-minute rush to get things done. In less than a year the huge marble stadium was restored thanks to the munificence of the Alexandrian millionaire, George Averof. So all was ready on 5 April (24 March in Athens since Greece was still on the Old Calendar) at 3:15 pm when the Royal Family arrived at the packed stadium. Some discreet official had even thought to decorate the two great herms found during the recent excavations with strategically hung wreaths so as not to offend the fine sensibilities of Her Majesty, Queen Olga.

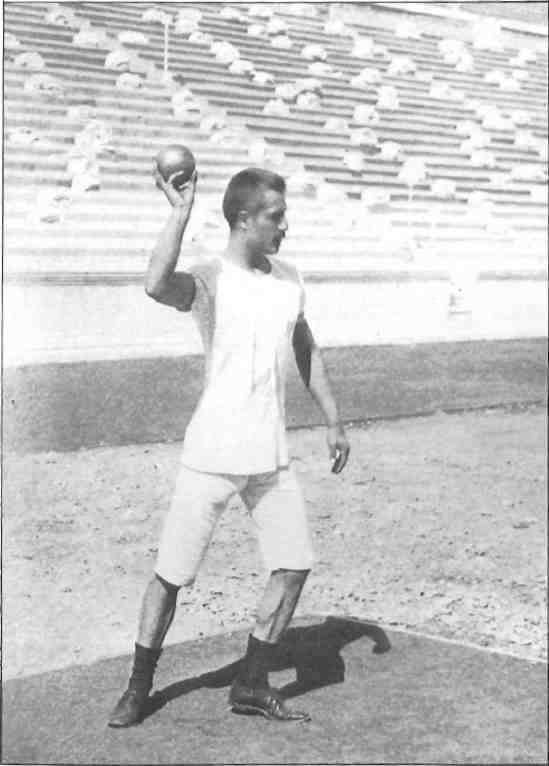

A statue of Averof, displayed not as a herm but in a frock coat, stands to the right of the stadium entrance just across from Dimitriadis’ fine bronze Discus-Thrower. A cast of this statue (another stands in Central Park, New York) is the focal point of the exhibition’s sculpture section which is very fine indeed. The 19th century academic style based on ancient Greek models has been so out of favor for so long, and in so many museums its examples are left unattended or dirty or pushed into corners or carried away to storage rooms, it’s a pleasure to see these works of Vitalis, Drossis and Vroutos buffed up, well-positioned and attractively lit.

For decades it was a central dilemma of Greek artists, living in a world of Western art where the battered ideal of neoclassical supremacy in sculpture was being overturned by new standards, to cultivate a modern sensitivity without turning against an admired and treasured past. Perhaps it is for this reason that these statues, all by Greek artists, have an integrity and inner life which had been lost in post-Canova, post-Thorwaldsen academic studios.

It may be a bit contrived, but as shown here the Olympic Games of 1896 themselves seem to have given Greek artists a renewed sense of vitality in the execution of the human body. There are many good examples of the work of Tobros on loan from the V. and E. Goulandris Museum on Andros. There is also a Rodinish group by Halepas and an unusually fine male toros by Apartis.

The exhibition of paintings is less satisfactory. This is, of course, partly due to the greater variety and higher quality of Greek painting for a century. Nicholas Gyzis himself did a lot of the art work for the Games and there are some very fine sketches of his on display. There is also Rizos’ charming “Athenian Evening” set against an idyllic Acropolis and full of the longeurs of fin-de-siecle French painting (but not Impressionist, of course!). There is also Parthenis’ wonderful art nouveau study in blue, “Women Bathing”, as deliriously cool as a dip in the Aegean. Fine as they are, the few works of Ghikas, Tsarouhis and Moralis haven’t much meaning here, and a word of friendly advice to the National Gallery on this matter: shred your ghastly Collection of Western Painting, and next summer put together a really fine exhibition of ‘The Generation of the 1930s’. Don’t charge the tourists this absurd 30 drachma fee but at least 500 drachmas. Give them something really exciting to see and talk about.

Finally, there is a room with two large TV screens where the visitor at a touch can choose from a databank film on every Olympiad since ’96, thrilling record-breaking moments, and video bios of most gold medal winners.