In the region of Karystos in Southern Euboea, there still exists an intriguing kind of building which has aroused the curiosity of generations of visitors and become the object of scientific investigation. These are the so-called ‘dragon houses’ of Styra and of Ohi, one of the highest mountains in the Aegean Islands. Mount Ohi, clearly visible from the east coast of Attica, commands the often tempestuous straits of Kabo d Oro separating Euboea from Andros. These dragon houses have been known since the 18th century when the English traveler John Hawkins took note of them in 1797. This was the period when Europeans traveling in Greece reached the most remote corners of the country and recorded information of great value today.

During the latter part of the next century the travels and publications of Ulrichs, Welcker, Girard, Baumeister, Weigand and Johnson, as well as the Greek scholars Gounaropoulos, Lambros and Sotiriadis, were the most important references and descriptions down to 1959 when systematic excavations were begun by Nikos Κ Moutsopoulos. The results of his devoted efforts were published in The Dragon Houses of Ohi which until now has been the basic reference source on the subject.

Equivalents of the term ‘dragon houses’ or drakospitia – ‘drago’ in the local Euboean dialect – are common to many parts of the Mediterranean and the Balkans, and they refer mainly to buildings of somewhat massive construction lying in areas difficult of access. Built mainly of megaliths, they have a mythical aura suggesting they were made by extraordinary beings. There is a fairy tale from the village of Platanisto south of Karystos called The Cave of the Dragon, fortunately preserved by the father of modern Greek folklore studies, Nicholas Politis, which very beautifully preserves a specifically Euboean version of a tale which refers to these strange structures and those who built them.

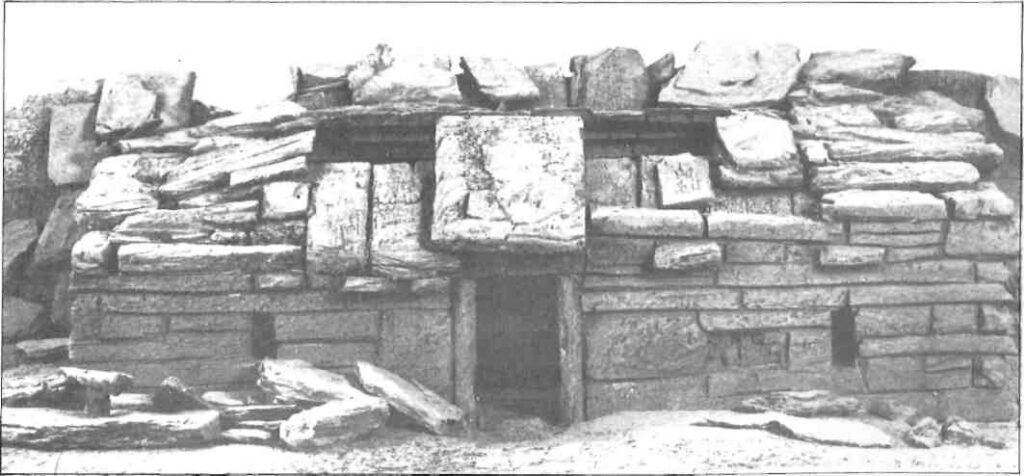

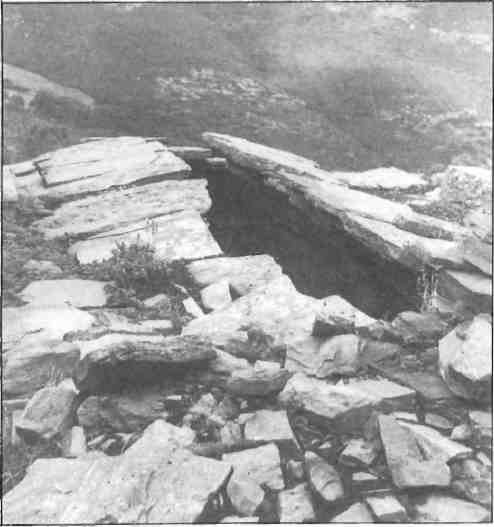

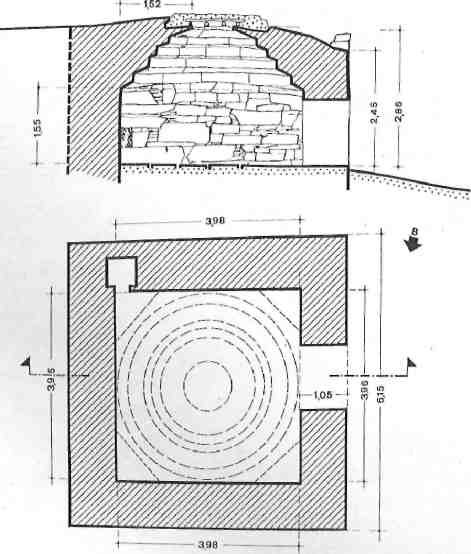

The sites of the dragon houses around Ohi are mountainous areas very difficult to reach. They are not strategic sites from which the surrounding areas could be controlled. Many of these structures are almost attached to the rocks close at hand, so there is no clear view in every direction. The area they occupy, rectangular or round, is often quite large. Some are five by ten metres in size. They are xyrolithia, dry-stone constructions made of local material without mortar, with thick walls comprising one or two rows of stones. The round structures feature a very ancient type of roofing similar to that found on Minoan and Mycenaean tombs. The lower courses of stone protrude a little and support upper rows which incline inwards until finally only a small aperture is left on top capped by a keystone.

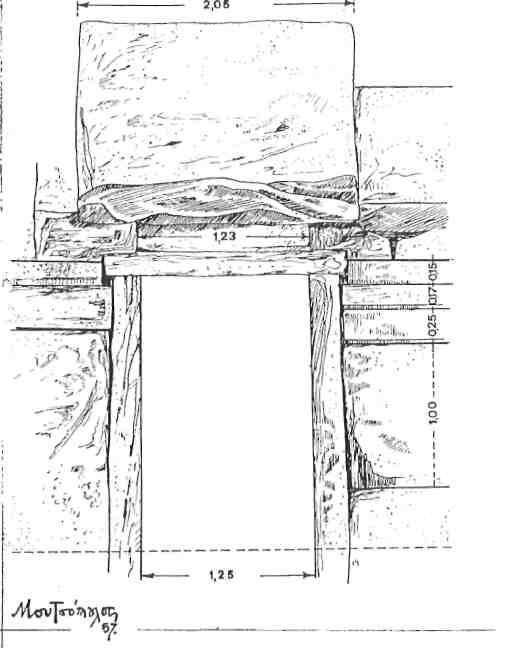

These buildings have a single entrance with a trapazoidal opening above the lintel to relieve architectural stress. The floors are made of flat stones which in some cases are well preserved. Some dragon houses may have had an upper floor, though this is not certain. The method of wall construction suggests links with strongholds dating from the Classical period or later, especially the fortresses of Phyle and Varnava in Attica which are of the fourth century BC. It is certain that the builders of the dragon houses of Ohi possessed great bodily strength in order to transport the large stones from areas all around and had a knowledge of statics, too.

Nevertheless, the dragon house type of structure and the method of construction have similarities with buildings of much more recent date in other areas, such as the mitata of Crete. These are to be found in the Lefka, or White, Mountains but mainly on Mount Ida in the area between Anoyia and the Idaean Cave, as well as on the nearby Nida plateau.

Some architectural elements, such as the ‘shelves’ which early travelers considered to be the pedestals of statues, or the ‘hearths’ found in the center or in a corner, and even the aperture in the roofs, morphologically connect the the dragon houses with the Cretan mitata. Due to these similarities, a theory has arisen that the dragon houses are recent structures built as cattle shelters.

Naturally, over the years, mistaken identification by over-zealous amateurs and the depredations caused by plunderers of antiquities have destroyed much of the evidence, but the archaeological remains, however few, must be closely studied to reach a more accurate understanding.

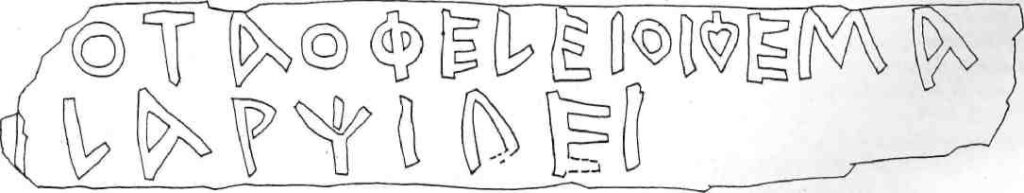

The position of the dragon houses at high altitudes, but closely protected by rocky bluffs, weakens the opinion that they were strongholds or control stations, whereas the theory that they are cattle byres of recent date is undermined by the ancient remains found both inside and immediately outside these structures. Indeed, the idea that they are ancient buildings is reinforced both by the antiquity of the architectural type, the method of wall construction, and the discovery of ancient remains and inscriptions.

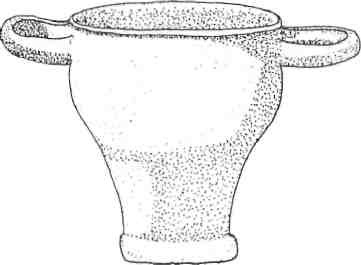

Chronologically speaking, the most ancient evidence is an archaic inscription written in the Chalkidic alphabet on a shell which was found in a deposit just outside one of the dragon houses. Numerous vessels of the skyfos type, with one or two handles, brought to light by the Moutsopoulos excavation, though local and difficult to date, may be compared with the few Attic samples found with them, which may be dated towards the end of the Classical or at the beginning of the Hellenistic period. Most significant in determining date are three types of Attic ware that have been found: jugs, two-handled skyfos and so-called ‘salt-cellars’. Together with the ceramic objects, the discoveries of a copper earring, an iron nail, beads of glass mixture, an arrow point and fragments of copper vessels, all help in identifying what the houses were. Dating from the two distinct periods, one in the early fifth century BC and the other from the fourth century BC, the pottery coincides with periods when contacts between Athens and Southern Euboea were known to be close. Although we have evidence that Athenian landowners settled around Chalkis at the beginning of the fifth century, very little is known of Karystos, though it seems that a community of people settled at the foot of Mount Ohi later in the century since Karystos was striking its own coins by the middle of the fourth century. The relationship with Athens at this time was more in the nature of an alliance than of conquest.

Karystos appears to have flourished in Roman times, too, for gold coins make their first appearance then and the city’s mines were in production. Of the fourth century AD Roman lamps that have come to light, one represents a cupid astride a dolphin, and coins minted during the reign of Hadrian have been found in the dragon houses of Styra, lying north of Karystos.

In one of the dragon houses of Ohi numerous single-handled cups found beneath the level of the floor suggest human use prior to the construction of the building. Consequently, the question arises whether the dragon houses date from close to or at a remote period from the deposition of the vessels that have been found. If one accepts the respect which those who constructed the buildings had for offerings that have come to light, then the answer is relatively simple. According to the inscriptions,the locations of these buildings cannot have been in use earlier than the archaic period and excavations corroborate this. The dragon houses then can be said to have been built between the sixth and fourth centuries BC. It is possible that offerings were originally deposited in some ‘rock shelters’ on top of which these ‘holy houses’ were later built. The evidence of lamps of the Roman, Graeco-Christian period attest to the very long duration of use these structures had, but one cannot accept the statement of Ulrichs, who called the dragon house “the earliest Greek temple”.

What then was the purpose of these buildings? The high quality and the character of the finds excludes them as guardhouses or shepherds’ dwellings. The animal remnants which have been found suggest answers that may be partly pieced together. For example, the inscriptions may be of a devotional nature, as are the ones in Styra farther north, which are thought to be offerings to the god Hermes or Zeus the Savior. The beads and earrings indicate a female presence in that rugged region, not the presence of a military station. The excellent quality of the pottery, both that of Attic provenance and the Roman lamps, too, casts doubt on the theory of Perrot-Chipiez and Ross, which suggests the involvement of semi-barbaric tribes as well as the guardhouse view of other scholars. The purpose of these buildings must have been of a more official character, although not of a funerary kind, as Thiersch has claimed, since there is no evidence of burials. Nor does it seem at all likely that the dragon houses were built by transhumants such as the Sarakatsani as others have suggested.

On the contrary, all the above evidence points towards the interpretation that the dragon houses were religious edifices honoring some ancient goddess, or some local worship similar to that which is known to have been practiced on Mount Hymettos. The rites probably took place both outside, and, in secret, within, as Pausanias has described in reference to practices elsewhere.

Besides the finds discovered inside the buildings, early travelers confirm the existence of an altar outside one of these houses and near the entrance – details already familiar from other ancient sanctuaries, as in the case of the Idaean Cave on Crete where the youthful god was originally worshiped and later replaced by the Cretan Zeus. The discovery of offerings relating to men (an arrowhead) as well as to women (necklaces) could indicate the worship of both a male and a female deity. The etymology of the term ‘Ohi’, mentioned by the scholar Stefanos Vyzantinos as deriving from the ancient ‘oheia’, meaning ‘sexual congress’, may indeed refer to the union of Zeus with Hera. Certainly the worship of Zeus would be appropriate to the presence of a high mountain, and why not in conjunction with his great consort?