He was born in Peking in 1924 of English and American parents and his upbringing was half the east-coast American world of Henry James, and half England, where he was sent to Stowe. He won an honors degree in Classics and American Literature at Harvard; he was just old enough to serve as a reconnaissance scout with the US Army in the Po Valley campaign.

But, very soon afterwards, Greece became his chosen field and remained so for the rest of his life. A fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens launched him on a wild and solitary hunt for Peloponnesian Crusader ruins and the resulting book, Castles of the Morea, (long overdue for reprinting) has remained a classic. These travels led him into steep mountain ranges in the throes of civil war where, often in great danger, he became friends of the combatants on both sides; his knowledge of the fierce realities of Greek mountain life became the raw material for The Flight of Ikaros (Weidenfeld and Nicolson and, in 1984, Penguin Books). It is the most brilliant and penetrating book on the bitter and often tragic aspects of Greek rustic life to come out since the war. He was uniquely fitted for such a task by his physical stamina, his classical and historical studies, his outstanding command of Modern Greek and its dialects, by the vigor and range of his style; psychological grasp, poetical flair and feelings of pity led him straight to the heart of his chosen world.

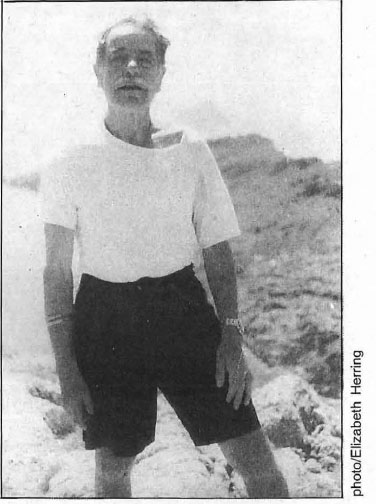

With his fine looks, clear glance, and the shaggy goatsherd’s cape with a bamboo flute in the pocket – his excellent ear for music was matched by a knack for songs – he always brought a tang of curds and woodsmoke back with him to Athens. All this turned him into a scholar gypsy, and everyone loved him. In spite of his gifts, his transparent integrity sometimes seemed to disarm him for life and he was plagued since early adulthood by epilepsy – seizures which could last a minute or more: it was one such untimely visitation that caused his death last month.

His marriage to Nancy Roosevelt, a daughter of E.E. Cummings, ended in estrangement and, through the absence of their children in America, much sorrow. I think he was happiest sleeping out on brushwood among the sierras of the Megarid where a goatherd godbrother pastured his flocks; or in talking all night in Athens with Greek literary friends or with Louis MacNeice, Robert Lowell and Professor E.R. Dodds.

His Athenian habitat prompted him to write Athens (J.M. Dent in The Cities of the World Series, 1967) a brilliantly original, resilient and iconoclastic dismantling of all accepted ideas about modern Greece, which set shock waves in motion. Another book on the same place, Athens Alive (Hermes Publications, Athens, 1979) is an assembly of historical texts from the fourth century AD to the eve of World War Two. Recondite and largely unknown, they range from Hellenistic papyri, Burgundian chronicles and Turkish firmans to the dispatches of Hemingway, all of them heavily annotated by Kevin to illustrate the age-old interference in Greek matters by foreign powers, especially in recent times.

These feelings – and allotting blame for the colonels’ dictatorship and for other wrongs to Greece – preoccupied him. He was active in forbidden movements against the military junta and, in 1975, he wrote a long, remarkable and moving poem about its violent ending, in which he took part, full of passionate intensity. The poem, of Waste Land length, called First Will and Testament, condemned Western leaders with the vehemence of Byron excoriating Castlereagh and, in 1975, he renounced his American citizenship and became Greek. He was the first foreigner to do so and the change was very important to him. His increasingly radical feelings never came under a party denomination: they were a kind of Tolstoyan aspiration, perhaps akin to Orwell’s pursuit of common decency. I think he was perhaps sometimes astray and very occasionally unfair, but never anything less than deeply convinced. Several things – the failed marriage, the distance from children, the troubles of Greece – had made the last two decades less happy than the others.

But, just before the end, everything had begun to change. He had fallen in love with a fellow-writer and poet, remarriage was planned, and he was preparing for publication his first novel. He was intensely happy. The fact that these prospects glowed removes all suspicion of suicide from his death. All this makes his sudden departure sadder still, and the disappearance of so brilliantly gifted a writer a greater loss to Greece and to us.

On 1 September, after a day of rock climbing, playing moiroloyia on his floyera, and discussing his novel, he set off to swim from the southernmost cape of Kythira to Avgo island: some six miles there and back. A sudden storm blew up a seven Beaufort-scale wind; night fell, and after a long search in darkness, with helicopters flown at dawn from Crete, hope was finally abandoned.

He vanished, 42 years to the day after first setting foot in Greece, heading for an islet full of sea-caves and gulls in a legendary reach of the Aegean.