Saturday, 18 August 1917, is a day that will always be remembered by the older inhabitants of Thessaloniki. The memory of it, too, must linger long in the minds of veterans of the British Salonica Force – should, by chance, any be still alive – who were there at the time. They may not be able to recall the date itself, but they will never forget the fire that occurred on that day, when nearly a square mile of the city burned down in the course of a few hours.

To Greeks it was an event in their history, but to the majority of the British – except those directly concerned – the catastrophe was, to a large extent, masked by the import of current war news. The Times, usually renowned for its coverage, could only afford a few lines on the subject. This lack of observance by the national press meant that Britain as a whole was unaware of the amount of Anglo-Hellenic understanding that was engendered by the involvement its soldiers and sailors readily accepted in the situation.

H. Collinson Owen was, at the time, editor of The Balkan News, and Official Correspondent in the Near East. Collinson Owen was the only member of the British Press who had devoted his whole time to the Macedonian Front, and it is through his eyes that we are able – through his book Salonica and After – to get a clear picture of the disaster and how the Force reacted.

It was a very hot day and the wind from the Vardar was blowing a gale, and had been doing so for two or three days. Owen, told of the fire by his maid during the Saturday afternoon, went up on his flat roof to look. From here, he had a view of practically the entire city and its surroundings; away up the hill in the northwestern corner of Turkish Town, a big blaze was in progress. The wind was blowing strongly and steadily in his direction. The fire looked, and seemed, a remote thing and people just stood on their roofs, free from concern, and enjoyed the spectacle.

The general impression among the populace not involved was that the fire would not spread far, that is from the half-wooden houses of the Turks and Jews in the native quarters – certainly not to the ‘better class’ parts of the city.

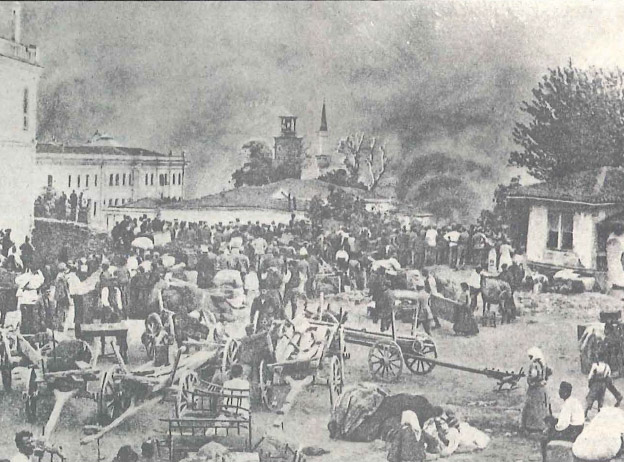

Egnatia Street was jammed with refugees carrying all sorts of things. The narrow streets were a slow-moving mass of pack donkeys and hamals carrying enormous loads. Greek boy scouts were doing excellent work; soldiers of all nations were standing around unorganized; ancient wooden fire engines spat out ineffectual trickles of water; and people with beds, wardrobes, mirrors, pots and pans and their most valued possesions – machines for sewing – were desperately struggling through the crowds.

There was a reluctance among the inhabitants to leave their homes until the last possible moment, and those living only a short distance from the conflagration appeared convinced that the fire would either not reach them or would pass by. As it was the Jewish Sabbath, many of the big shops were closed, and jewellers and others did not attempt to try and save their stocks until a late hour.

At first, the Allied Forces hesitated. It was not easy to say in whose hands lay the material and moral responsibility for tackling the fire. With the outbreak attaining alarming proportions so suddenly, everyone was taken off guard: then it became apparent that it was everybody’s business.

A company of Durhams arrived to form a cordon, then further Allied patrols came up. A little later, dynamite was tried, but the flame leaped over the breaches made in buildings. It was thought that the Egnatia Street, being about 30 feet wide, might serve as a barrier and cut off the native quarter from the more modern half of the city. But the flames cleared the street without hesitating when the time came.

The hot wind blowing behind created a huge forced draught, and flames leaped ahead of the main fire to other buildings already tinder-dry. It was soon very obvious that the whole of the city, with the exception of the long suburb stretching along the sea eastwards, was in danger.

,At about nine o’clock, the wooden roof* of the bazaar, which led from Egnatia Street down towards the waterfront, caught fire. It was the beginning of the end for the commercial quarter.

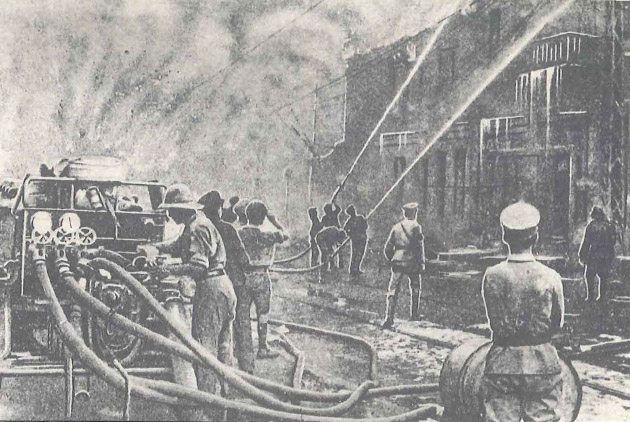

Several hours earlier, two new British motor fire engines had entered the fray. They had arrived from England a few days previously and were not completely ready for service. Both engines did splendid work, and at one time as much as 4000 feet of hose was coupled to one of them.

The driver of one engine remained at his post without sleep from eight pm on Saturday until six the following Tuesday morning. One engine was in action for 17 days and the other for ten, there being many sporadic outbreaks, with parts of the city smouldering for a fortnight.

The multitude of refugees was driven into the last parallel of streets that lay near the quay: then it was realized that even these would go up in flames. The refugees flowed to the farthest limit, into the docks. It was here that they sat in their thousands, squatting hopelessly on their beds and bundles; babies whimpering; parents and children just gazing vacantly before them.

Then a magic change came over the scene. The British Army received an order to help. From all directions the transport service poured everything it could muster in the form of lorries and motor vans into the town. Their order was simply to take up the refugees and what they had saved and hurry them out of danger. The men behaved with the utmost, care and consideration. The vehicles were loaded at a tremendous pace, and as soon as they were full they would be off along the Monastir Road to deposit their charges in a camp and return for more. In all, 80,000 homeless people were dealt with.

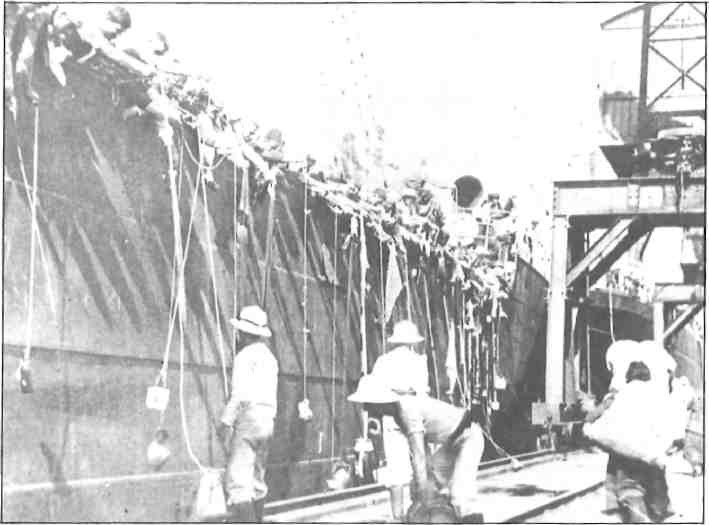

The Navy, too, did its share. Lighters were run into the sea wall, packed with a medley of bodies and taken off to various ships in the harbor. The sailors, like their counterparts in the Army, carried children and old people on board and carefully deposited them.

For the record, the fire began at 3 pm on 18 August, and the fiercest of the burning was not over until 32 hours later. It was believed that it all began in a little wooden house on Olympos Street, where refugees who were cooking spilled some oil. The Salonica Fire is said to have been the greatest in insurance history up to that time.

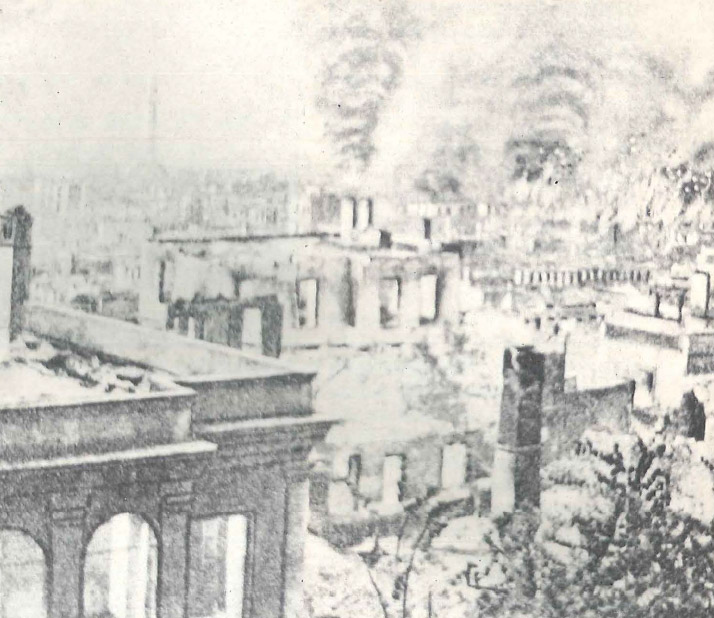

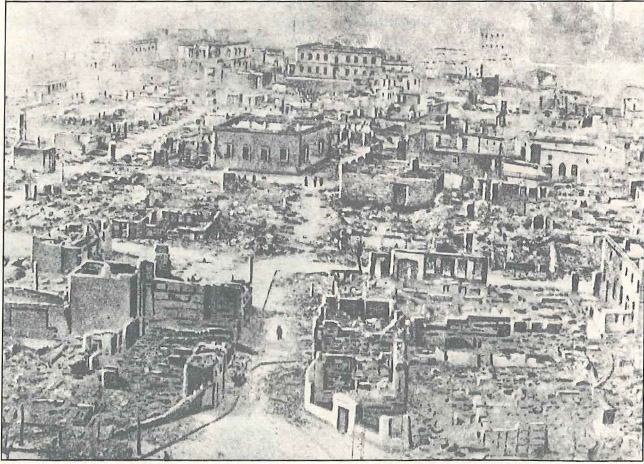

The area of destruction was close to a square mile, and 9500 houses and commercial buildings of all kinds burned down. The damage was estimated to have been more than £80,000,000 of which nine tenths was insured, British companies being far the most heavily involved.

The greatest loss was the magnificent Byzantine Church of St. Demetrios, dating back to the fifth century. The famous church of St. Sophia, dating back to the sixth century, was saved, partly due to its wide courtyard.

There were 55,000 Jewish refugees, 12,000 Greeks and 10,000 Moslems. The difficulties of finding shelter for all these souls at once was very great. Many were accommodated in camps organized by the Allies, of which three were set up at Karaissi, Dudular and Kalamaria. The British gave 1300 tents and provided shelter for over 7000 people. There were many warm tributes paid to the British during and after the fire.

Typical is one which appeared in the Greek journal Fos:

“The refugees were led on the night of frightfu lness and destruction with indescribable affection far from the flames and found themselves under the protection of an elect race whose name is spoken with gratitude by those who have been so greatly tried … The life of these ardent apostles of humanity and goodness amongst us has been unstained and clean, and the Greek appreciation of it has been sincere and warm … “

“Although there has been but little time in which so difficult an installation could be effected, nevertheless British energy, which is the marvellous and amazing quality of this great race, was able to gather humanely, shelter and feed a great number of refugees. The houses in which the refugees are sheltered are well-roofed and the tents placed in perfect line, with English exactitude. There lives an entire population which yesterday was happy, but today is ruined and living on charity of powerful friends.”

Such eloquent praise must have made the British Tommy blush as he read the translation in The Balkan News. But there can be little doubt that he earned it.

The whole episode is ample evidence of the Anglo-Hellenic relationship that existed at the time. The British Army, while being subjected to the rigors of Macedonian winters and torrid summers, often in difficult circumstances, still found time for compassion. Likewise the Greek people, in their hour of disaster, although beset with their own problems, were not slow in recognizing the gesture.

Note: The picture postcards, no doubt brought back from the war by a soldier who had been involved in the incident, were found mounted in a dusty frame by the author in a flea market in Bath.