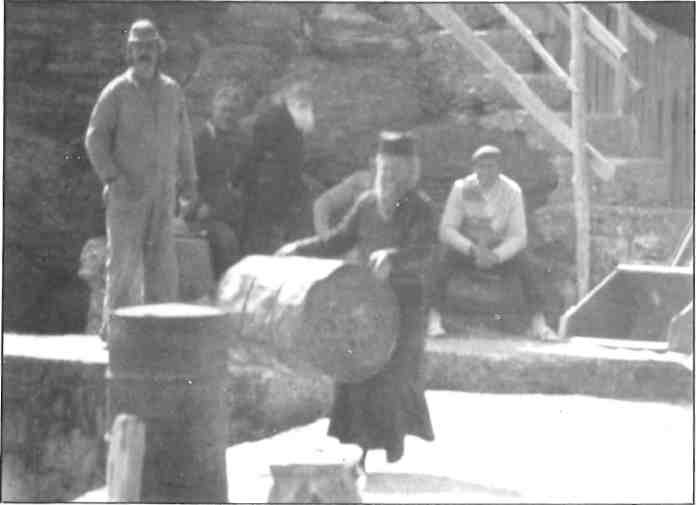

The winds sweep the visitor ashore at the sacred harbor of Dafni. Here he is met with the hustle and bustle of merchants, woodcutters, pilgrims, tourists, sailors, and monks – all hard at work. All manner of cargo and luggage is off-loaded and exchanged for other goods for export: walnuts, lumber, olives and olive oil, crates of icons and incense, products of the Holy Mountain’s numerous monastic industries. Faces all round gleam with sweat – swarthy complexions burnt by sun and salt spray.

My first impression is of entering a teeming workshop: can this be the Holy mountain of Athos – the spiritual home of hermits and of the other-worldly ‘Fathers1 of Christian Orthodoxy: the great mystic theologians of the Christian East? Is this the place from where, in the 14th century, St. Gregory Palamas (1296 – 1359), father of the revolutionary “Prayer of the Heart”, led the revolt of Orthodox Byzantium against the invading theology of Thomas Aquinas and the Roman Catholic Church? Is this Athos truly a place of miracles and of great souls afire?

My reflections intermingle with the myriad worldly activities of the solitary harbor of Dafni and yet, come to rest on the looming heights above this little port town. Here, rising up to 6500 feet above sea level, are the rich, dense forests of the Holy Mountain, the precipitous heights that lead its “black angels” deep into solitude and the abandonment of the ordinary world.

It was on these craggy heights, before AD 850 and the establishment of monasticism per se, that the first hermits were drawn to practice the “eremitic” or solitary life of prayer, renouncing all forms of secular or even religious communalism.

The busy port town is the last emblem of Greece’s outward-looking, gregarious persona: here, at busy little Dafni, the visitor passes through the first gate into the recesses of the Greek soul.

Mount Athos, located in the region of Halkidiki, a four-and-a-half hour bus ride from Thessaloniki, occupies almost the entire expanse of the Akti Peninsula, some 35 miles in length. Under its own jurisdiction, with a status akin to that of the Vatican, the Holy Mountain draws its monks from all over the Orthodox world – Serbs, Bulgarians, Russians and other nationalities, as well as Greeks. They are now, according to the Holy Mountain’s Constitutional Charter of 1926, all Greek citizens. It was this provision which allowed the Greek government to expropriate some monastic territory to house the Asia Minor refugees who flooded the country (almost 1.5 million) after the Greeks lost the Greco-Turkish War of 1919 – 22.

The tiny island of Amouliani (where I’ve lived, on and off, for years as an anthropologist) and the villages of Nea Rhoda and Ouranoupolis nearby all came into existence at that time. Their refugee settlers now operate all the ships and caiques that service the Holy Mountain with its considerable commercial traffic.

It was on board a Dafni-bound caique 20 years ago that a visiting Athenian theologian concluded:

“There is indeed a Greek soul!”

“So souls, too, will now be issued passports!” an old monk aboard wryly retorted, an oblique reference to the then current dictatorship of Colonel Papadopoulos which had been harassing the Holy Mountain. His eyes flashed as he receded back into silence.

The journey to Dafni is generally a pleasant one, 40 minutes from Ouranoupolis, “City of the Sky”, the last lay town on the peninsula before the approach of the monastic community’s foreboding forests. These forests stand as a landward barrier, dark and impenetrable – or nearly so.

There is a story of a German woman who crossed into Athos, where no female is allowed, from Ouranoupolis. She entered where the only female footsteps ever reported were those of the Ever-Virgin Mother of God, the Most Holy Theotokos, as she wanders in Her holy garden of Athos, dedicated to Her exclusively of all females.

The German woman was discovered unconscious, as the story goes, nearly dead of exposure in a monastery vineyard after having wandered into the maze of Athos’ forests. She had reached only as far as the first of Athos’ 20 great monasteries – Hilandri (the Serbian monastery) – before she dropped in exhaustion.

“Lucky the wild boars didn’t get to her and the weather was still warm!” an old monk exclaims as he recounts for me the uncommon tale.

But Holy Athos is not misogynist. Quite the contrary. If women have not been permitted here since 1060, it is because this greatest of Orthodox Christian monastic enclaves aspires to the virginity of the Holy Virgin Mother of God Herself; they chant to Her who holds the key to human immortality, daily at midnight services, on Sundays and holy days; She is the key to theosis – to the metamorphosis of “Man into God, and God into Man”, as St. Athanasios the Great formulated it.

On the Holy Mountain not even female animals are kept and bred, again of the pledge of chastity each monk must take to the Virgin Mother: “She is my mother, sister, wife and daughter.” She is the “mantle” upon which all creation rests, the monks chant, the Platitera Ton Ouranon, since She contains the seed of God the Father, God the Son, Creator of the entire universe – and so, it is She who gives birth to all the world, the sons and daughters alike of all redeemed mankind.

The German woman was sheltered and nourished back to health by astonished monks who perceived her survival as one of a million tiny and greater miracles which happen daily on the Holy Mountain.

They bade her farewell at Holy Dafni as she again embarked for the outside world. Rumors swiftly spread that although she must not be seen again on Athos, she had become Orthodox; she had slipped in only because of her zeal for the “True Faith” (which is the literal meaning of “Orthodoxy”); she had become a monk herself, they gossiped!

“Bah,” another monk tells me. “Women could never enter here at Dafni. Even if dressed as a man, we monks can smell a woman right off!”

But women did enter the Holy Mountain at Dafni once – by force. During the Greek Civil War (1944 – 49), when Halkidiki was a leftist guerrilla stronghold, the communists sent a patrol of women soldiers to search for political, anti-communist refugees.

“They came ashore with bandoliers, with rifles and other arms,” the same monk recalls. “They searched through the monasteries, prying here and there… They dressed like men, but they were even worse than the male guerrillas. Totally unrepentant! They never found who it was they were looking for, but they warned that they would return again if they found cause.”

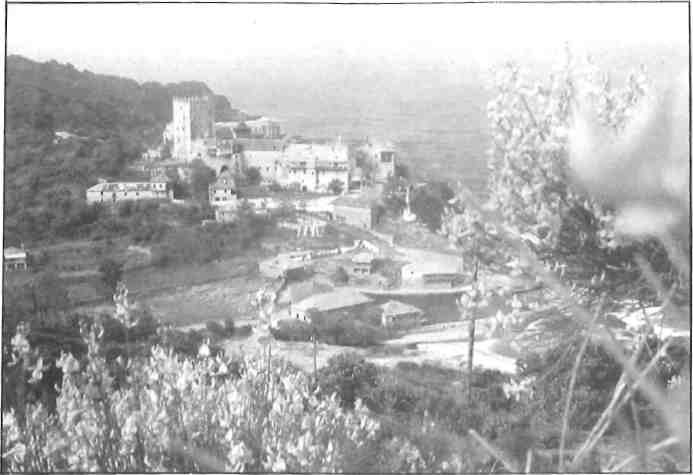

Beyond Dafni, then, one sheds the mantle of the world and approaches Heaven’s gate. The next way station is Karyes, a medieval town, which, totally unchanged in almost a thousand years, awaits the pilgrim. With unpaved roads, enormous gardens, great stone buildings, and no electricity, Karyes extends outward to blend into a rolling valley overgrown with rich vegetation of immense variety.

Karyes is the administrative capital of the Holy Mountain. Here the visitor presents his passport, acquired in Thessaloniki or Athens; to the authorities, and must await a personal interview with the Hegemon, or Spiritual Father, of the Holy Mountain.

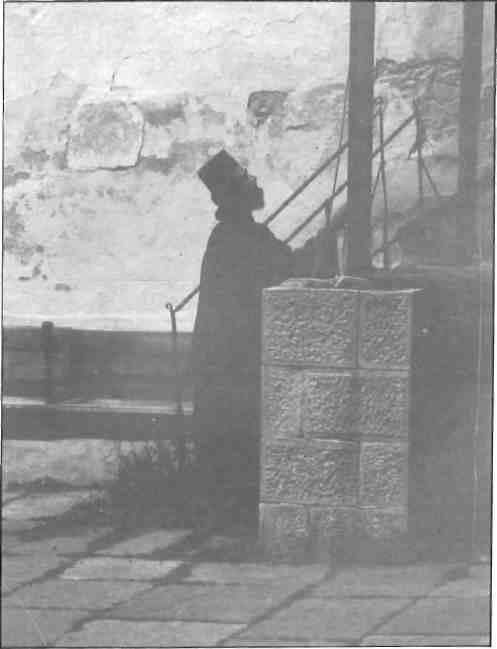

Sometimes a man is tied up in Karyes for days awaiting an audience. Again he sees the busy monks at work everywhere.’ Some are out in their vineyards or gardens, the sleeves of their soiled black cassocks rolled back, pruning or hoeing or chopping underbrush, gathering wood. There are monk carpenters here, with little shops, icon makers, and worldly merchants who, even if not monks themselves, and with families on the outside, become extremely pious from living and working here.

There are tavernas for buying food and drink to sustain one, and housed in such a taverna along the main road leading from Dafni, unpaved and scattered with boulders, I watch the rickety bus rattle in daily from Dafni, filled to overflowing with male visitors. Others arrive on foot along the same road, or are carried by donkey guides over the mountain ridge which separates these two Athonite urban centers.

I enter a great hall in the Palace of the Hegemon and Γ am asked to wait by a stubble-bearded, non-clerical attendant. Many of the locals are employed here as servants and workmen. The monks of Athos have dwindled to just over a thousand; its numerous estates require hundreds of hired hands to altend to its thousands of square hectares of fertile, productive land. Besides the 20 great monasteries, there are a dozen “sketes”, or monastic refuges, and many hermitages where more reclusive souls seek greater solitude.

Waiting and abandoned, I sit alone to contemplate what I might be asked and what responses I should provide His Eminence. Suddenly I am called. I enter a great room. The Hegemon of the Holy Mountain sits at his large mahogany desk. Great icons resplendent in precious metals and stones cover the walls. On my side of the desk are two young, bearded monks in fine, clean, black monastic robes. His Eminence bids me present my passport.

“Ah, you are not Greek,” he notes sternly in Greek.

“Yes, I am American.”

“And what would you be interested in here?” he asks.

“I have come to see the “thisavrous”, the precious treasures,” I foolishly answer.

“Treasures?” he chides.

“Yes,” and I repeat my formula: “thisavrous”.

“Here, my son, the only treasures are those of the heart! Do you not seek solitude and prayer?” he asks incredulously.

A young monk motions to me and I move closer to him as the Hegemon reexamines my papers. The young monk bends over close to my ear and whispers in Greek: “One must answer, Νa proskinoso: Ί have come to worship.” This is the proper response.

When the Hegemon looks up again quizzically, I answer, “I have come to worship, Your Excellency!” He is delighted by my informed response and stamping my special visa bids me look after my soul.

“You are free to travel wherever you please on the Holy Mountain,” he proclaims, “for two weeks’ time.” End of audience. I bow and, when he extends his hand, I kiss it dutifully and depart.

A young Yugoslavian travelling companion awaits me outside. “Well, how did it go?” he asks.

“I am to tend to my soul!” I answer.

Here, on Athos, just as the monks bend their backs to cultivate the rich garden of the Most Holy Virgin, so also do they labor to procure the fruits of the soul: for it is here, as they say, that “heaven rests on earth’s back.”

It is here that one sees how, in the world, the other-worldly philosophy of Orthodoxy takes root. Monasticism is not easy. It is a struggle with the inertia of worldly matters. It is a discipline of mind and body and spirit. Even if one seeks solitude, one must labor in the Virgin’s garden, just as She labored to give worldly form to the Son of God. The lessons of Orthodoxy take root through pilgrimage and prayer, through ordinary labors and extraordinary labors to mold the flesh – not to flee it – into the image of God… Theosis. I am pleased that I am becoming an initiate into the mysteries of the heart!

And if my formulaic response to the Hegemon is born of the world’s foolishness, what an array of worldly treasures, in fact, intermingles here with the true treasures of spirit. For Athos is a genuine treasure trove of sacred objects and holy relics. Many of these are of great antiquity – each individual artifact often of inestimable value – the gifts of Byzantine emperors and empresses and of the czars of Holy Russia, of Slavic princes, the donations of the great patriarchs of Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria – even of the Popes of Rome.

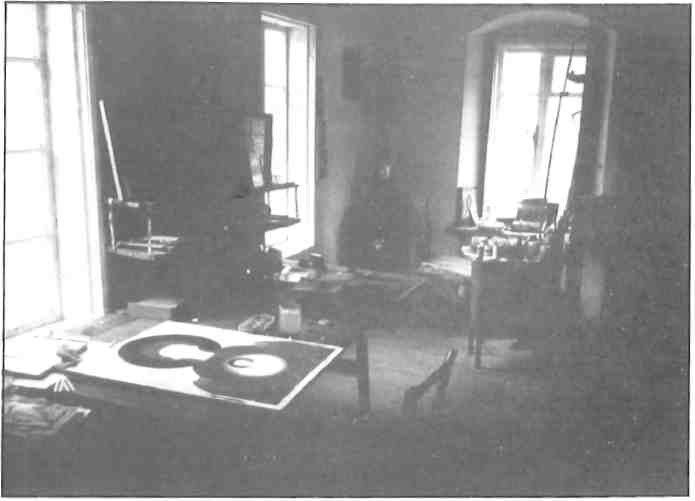

Athos is famous for its own school of iconography which still flourishes today. After the fall of Constantinople in 1452 to the Turks, Athos became the center of sacred Orthodox Christian painting – or iconography. Among its celebrated icono-graphers is Manuel Panselinos, whose startling, original frescoes decorate the Church of the Protaton, the central cathedral of the Holy Mountain at Karyes, as well as the cathedral of the monastery of Vatopedi (built shortly after the Great Lavra in the tenth century). With the end of Imperial Byzantine patronage, mosaic works were replaced by those of fresco: but several monasteries still retain rare and beautiful examples of one of Byzantium’s highest art forms – at the monasteries of the Great Lavra, Vatopedi, Stavronikita, Xenophontos, and elsewhere.

The 16th century was perhaps the most important period for iconographic art on Athos with the coming of what is called the Cretan School. The Cretan School began in Greece at the great monastic enclave of Meteora and, led by one Theophanes, reached Athos later, where it took root and flourished, creating some of the best examples of its imaginative and colorful style. Vatopedi, Lavra, Dionysiou, and St. Paul’s all preserve masterpieces by Theophanes and his disciples.

All the greater and lesser estates are adorned by wall paintings and panel icons, many glowing with gold and silver and jewels, illuminated by the light of beeswax candles and by the red and gold oil lamps adorning the myriad churches and chapels. The eye is dazzled and drawn to the sacred figures of austere saints and martyrs and to images gleaned from Orthodox dogma: the life of Christ and of the Virgin; of the Holy Apostles and Evangelists.

At first, these glowing figures, these great and precious works of art, are disorienting, but then the soul settles into itself and joins them in this visual exaltation of God’s glory and of the mortal, material sacrifice of His Son. It is an article of Orthodox theology that all this outward beauty is only an emblem of the glory to come: iconography is “a window on the spiritual world,” according to St. John Damascene; it is a work of the Holy Spirit which, the Greek theologians expound, guides the soul on its pilgrimage of spiritual metamorphosis. This world and that are inextricable intertwined -matter is sanctified by the Holy Spirit and mankind is invited to the banquet table of the Holy Angels in the here and now.

Nowhere is this doctrine of mortal glorification more perfectly explicated than in the great spiritual guide of Orthodoxy, the Philokalia, written by St. Nikodimos the Hagiorite (1749 – 1809), one of the most prolific scholars of Athos. “Philokalis” means literally “love of beauty”, which is also love of

the true good, for “kalos”, the Greek word for beauty, also means the “true” and the “good” as well as the beautiful.

The Philokalia was collated by St. Nikodmos as a compilation of the mystical teachings of the greatest Orthodox holy men, beginning with the early Christian era; a guide to the life of prayer and “spiritual athleticism”. It contains, in particular, the most profound teachings on the centrality of the ‘Jesus Prayer’ – the mystical “Prayer of the Heart”. Since its first publication in Venice in 1782, the Philokalia has become a cornerstone of Orthodox Christian teaching. It has been translated from Greek into Italian, German, French, English, Slavonic and Russian. Perhaps no other single work of piety has so deeply affected the Orthodox world and given more definitive form to the radical doctrine of Christian repentance and love.

My companion and I spend a week, on foot, travelling to Greek monasteries and sketes, or dependencies (some larger than the monasteries which spawned them), and stop at a few hermitages to break bread with welcoming solitaries. Of the 20 monasteries, 17 are Greek, one is Russian, one Bulgarian, and one Serbian. Of the sketes, one is Bulgarian, two are Romanian, two Russian, and seven Greek. The hermits generally cluster in the vicinity of a common church, or kyriakon – from the Greek word for Sunday – since it is only on the Sabbath that they leave their haunts for communion in the liturgy.

The weather is turning bad; it is late autumn. The monks warn us that we may be trapped here indefinitely, awaiting a caique. So the young Yugoslav and I part ways: after all, I will return to nearby Amouliani.

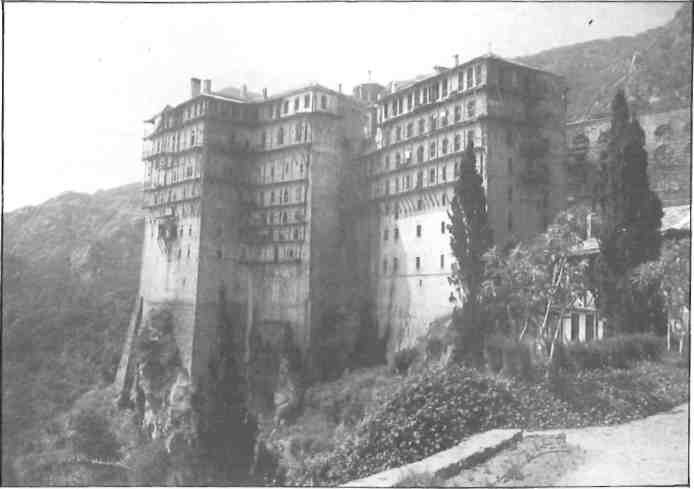

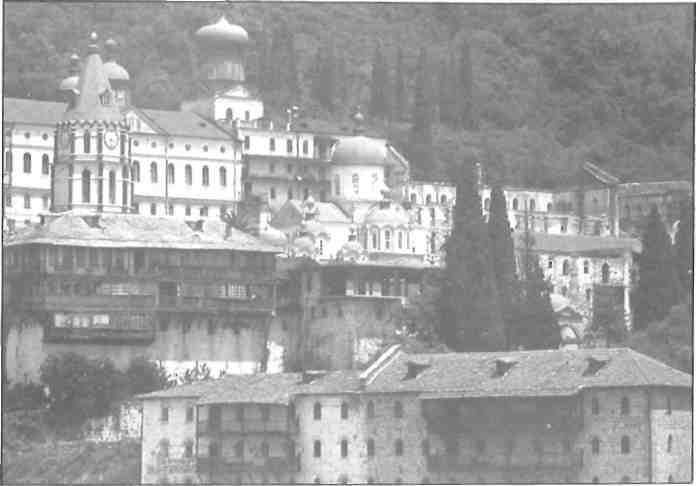

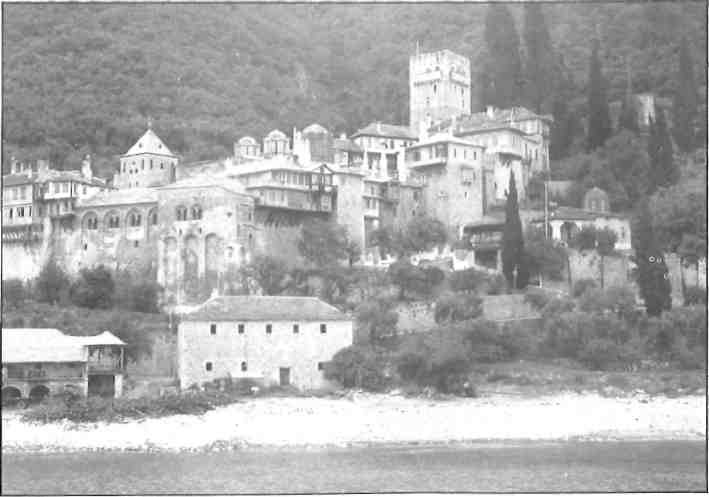

Continuing my pilgrimage, I arrive at St. Panteleimon, a Russian monastery established before 1400, situated above a seaward cliff on the western shore of the Athos peninsula.

Like all the Athonite monastic estates, St. Panteleimon’s is a quadrangle of buildings surrounding a central church or katholikon. This monastery has undergone centuries of additions. At the height of its architectural glory, in the 19th century, St. Panteleimon’s was greatly embellished by the Russian czars.

Their appreciation for monasticism was influenced by Tolstoy and other eminent Russian writers who, in turn, were influenced by the Slavonic and Russian translations of St. Nikodimos’ Philokalia. It was especially Dostoievsky’s Brothers Karamazov, with its portrayal of Alyosha and the saintly monastic, Father Zossima, which inspired the czars to patronize the Holy Mountain so lavishly.

A small band of monks, all Russian, now dwindled to only eight or nine, inhabits the giant monastery which easily housed a thousand souls before the October Revolution of 1918. The Russian monastery follows the cenobitic rule, or typikon, laid down by St. Athanasios the Athonite, founder of the Holy Mountain’s first and largest monastery, the Great Lavra, established in 963.

Orthodox Christian monasticism differs from that of the West in that there are no special orders of mendicants or teachers. Orthodox monasticism focuses entirely on the inner life of solitude, continuous prayer, and personal ‘glorification’. The cenobium is a communal rule where all the monks share in common the property of the monastery, dining together and submitting themselves to the authority of an abbot who leads them in their personal struggle towards holiness.

The Russian abbot, a starsy, is now ancient; and although he is friendly, we cannot communicate, since he and his Russian monks, although residents of the Holy Mountain for over half a century, still barely know Greek. From this fact alone, it is clear that they have maintained the sternest asceticism and seclusion – even from the numerous surrounding Greek monasteries, sketes and hermitages.

I join them at their communal meal, after midnight services, where the Russian monks appear mysteriously, as if from nowhere, abandoning their solitude to pray and commune together as a symbol of their shared brotherhood in the life of Christ. They focus their attention on their meager portions of vegetable stew and bread: the monks of Athos are vegetarian – allowed cheese, fish and olive oil only on special feast days. They eat in silence in their abandoned trapeza, or refectory, while one of their number reads from the lives of the Saints in Old Slavonic, texts dating back to the conversion of Russia at the end of the first millennium. Luckily, their cook is a Greek monk who whispers to me that he can offer me an extra portion of stew if I so desire.

Left alone in a large, communal boarding room with a fireplace, the only Russian monks with whom I come into contact are those who gather for prayer at midnight. A solitary knock on my door rouses me to join them in the monastery’s magnificent cathedral, but by the time I reach the great oaken door, the mysterious Russian monk has already departed. The Greek monk and I become soul mates as I frequent the kitchen to eat my promised extra portions and chat with him as he offers me tsipouro, a potent licorice-flavored eau de vie manufactured on Athos.

He is a gruff old fellow who insists I not kiss his hand – a common act of devotion here. He insists that he is not a holy man. He has come here, he explains, to “chase after holiness’1, and he is apparently deeply skeptical of his ability to transcend his former life as a sailor. He tells me of the ships he travelled on, like many Greeks of humble origins, from Tokyo to Buenos Aires, to New York. Now, without a suitable pension or close relatives to look after him, he has come to Athos seeking shelter and a resolution to his life of wandering.

One day, while I roam about St. Panteleimon’s dusky, abandoned corridors, passing empty monks’ cells once occupied by generations of struggling, solitary ascetics, I come across the Russian abbot. He is gazing intently, from the top storey, out across the open expanse of the Singitikos Gulf. Recognizing me, he smiles gently and bids me join him. He is visibly excited and clasps my hands.

“Look,” he says in broken Greek. “It is from here that the Patriarch will come!”

He is awaiting a miracle. I pity his poor, deranged delusions. He expects the Patriarch of Moscow after over half a century to come to reclaim the great, silent Russian monastery and to bring a new generation of younger ascetics to revitalize the dying institution and, thus, begin the redemption of Holy Russia: to wrest his fallen, atheist motherland from the hands of the terrible Bolsheviks.

“Miracles!” he whispers in his thick, barely intelligible Russian accent. “Miracles are the answer to prayer!” And he quotes St. Paul: “Pray unceasingly!”

I am troubled by this pathetic old man, by the abandonment of this once great center of Russian spirituality and pillar of Holy Orthodoxy. Is Athos nothing more than a deranged visage of the past, a medieval monument of decaying churches, a symbol of the decline of spirituality in our self important, haughty age of materialism? Why have I come here? I am now trapped by the bad weather, languishing day after day in isolation. Even the Greek monk is nowhere to be found. I am left all alone to ponder the irreversibility of history – the steady decline of faith and he end of the age of miracles.

Night after night I respond to the solitary knock on my chamber door, motivating myself to join these ravaged old men in their constant ritual of prayer and fasting, of continual repentance on behalf of a world that has renounced their faith in the miraculous. 1 slip deeper into my own sullen refusal to succumb to the delusions of Athos’ forlorn piety. Nothing but a miracle will save me, I fear, from the cynicism that is creeping upon me.

After countless days of hapless introspection, I begin to despair. When will I be rescued from the Holy Mountain – from the purgatory of these inflamed hermits?

Suddenly, one day, I awake to clear skies. It is already late in the day. I wrestle to free myself from the lethargy of my wait and quickly dress to go out to see if there is any hope of departure.

As I approach the little wharf of the Russian monastery, I am shocked to see the abbot in his finest priestly vestments together with the assembly of Russian monks. They are carrying Imperial Russian standards adorned in gold and purple in the old Byzantine style. They are carrying censers and bejeweled crosses and holding aloft a great, ancient icon of the Virgin Mother. Have the abbot’s personal delusions now spread to others as well? Have they all fallen victim to hysteria?

“Look,” the Greek monk greets me, “We await the great Patriarch of Moscow!”

And, sure enough, as if appearing from a cloud of salt spray, approaching our shore is a flotilla of caiques and Greek patrol boats. Flying aloft from their masts, along with the blue and white cross of the Greek flag, are innumerable Byzantine banners just like those carried by the Russian monks! There, at the prow of the lead boat, beneath the standard of the double-headed eagle – once the Imperial Russian emblem – stands a giant of a man in bright scarlet robes with a long, flowing white beard; and, encircling him, also in scarlet robes, grasping against the wind tall crimson Russian caps, stand a group of younger prelates with golden, youthful beards. It is indeed Patriarch Pimen of Moscow, coming to reclaim the Monastery of St. Panteleimon – hastening to initiate the repentance of Holy Russia and a new age of Athonite miracles.

I was able to depart with the patriarch. On our voyage back to Ouranoupolis, and then on to Amouliani for me, I reflected upon the lessons which the Holy Mountain still offers a world in rebellion against piety and faith. Would the Soviet regime one day truly repent and allow a return to Orthodoxy? Would Athos survive as the heart of Orthodox Christianity?

Athos’ lessons are those which quietly penetrate the pilgrim’s life, strengthening one’s resolution to pursue the difficult course towards spiritual awakening in an age bereft of miracles.