The beautiful and famous village of Lindos on Rhodes has a museum in one of the ancient mansions inhabited by the Knights of St John, but visitors wishing to learn something of the contemporary history of Lindos would do better to head to the Arches restaurant in the main square instead and ask for its co-manager, Mihalis Mavrikos.

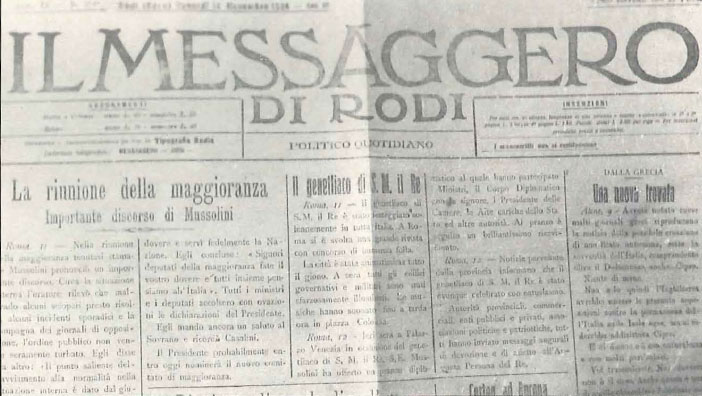

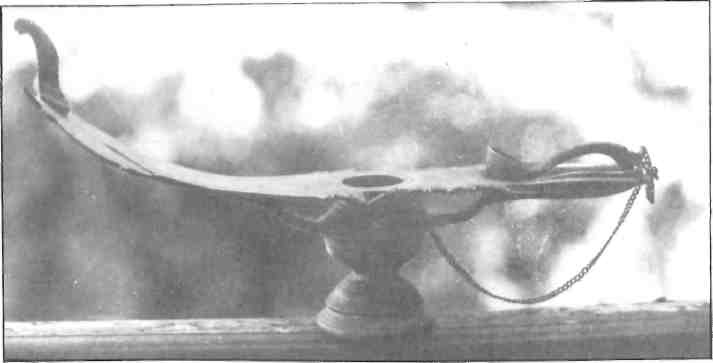

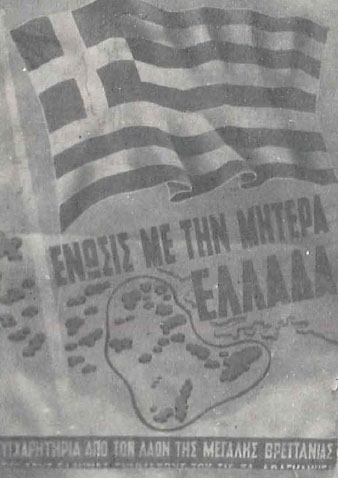

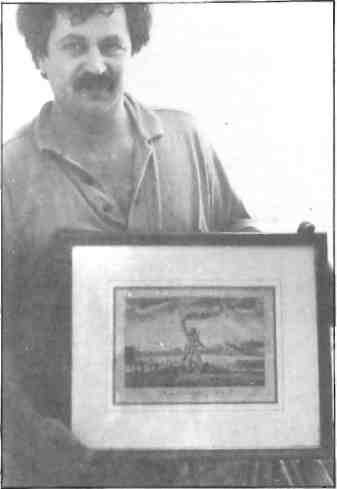

The 33-year-old Mavrikos not only has a master’s degree in international relations from the London School of Economics, but has spent the last ten years putting together a private collection of artefacts which tells the history of Lindos in the 20th century in a unique and comprehensive way. The collection includes photos, kitchen equipment, books, envelopes and stamps, official documents, letters, postcards, folk art, maps and newspapers dating from Lindos’ Turkish, Italian and Greek periods.

Although Mavrikos considers himself an amateur historian and has made no attempt to exploit his collection for personal gain, news of it has reached the mass media. Two years ago, Greek TV sent a camera team to film Mavrikos’ collection and interview him. The resulting show, titled Mama Lindos was broadcast in 1988. A German magazine has also done a similar kind of story, which will be published in a comprehensive feature on Rhodes in the autumn.

Mavrikos got interested in the history of Lindos when he was a child. “I was given two post cards from the Italian period by my grandmother. She had lived under the island’s Italian occupation which lasted from 1912 to 1943. One of the cards showed Lindos in those days. I was struck by the beauty of it and, in talking to her about her life, came to realize how important it was to preserve the past and keep it from being forgotten.”

Mavrikos began collecting seriously at 23, when he graduated from college and decided to return to Lindos. First he went to his own family, a large and illustrious Rhodian clan, and got them to dig around in old trunks and safes for memorabilia. Then he began asking friends and neighbors to do the same. He also used his own funds to buy items from private individuals or at commercial auctions in Athens.

“The collection just kept growing over the years,” says Mavrikos, who is unable to place a monetary value on it. “It filled one room, then another and another in my house, and its focus widened as well. To delve into the history of Lindos naturally leads one to the overall history of Rhodes and then on to the entire range of Dodecanese islands,since they shared so often a common fate. But that’s where I’ve had to draw a line – at the Dodecanese. One man can only do so much,” he laughs.

Proud as he is of his collection, Mavrikos is also disappointed that it is not being made available to the general public. “Since I don’t have the space or resources to open a gallery, my hope is that the municipality of Lindos will house the collection in its museum and charge a small entrance fee which will go towards its upkeep and funding staff. I don’t want a single drachma for myself,” he emphasizes.

“The problems is, the Archaeological Service has kept the Lindos Museum shut in recent years. It’s listed in all the guide books, but when tourists show up at the door, they find it locked up tight.”

The mayor of Lindos has made a personal appeal to the Archaeological Service and to Greece’s Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri, for help in opening the museum, but his letters to date have not been answered.

Officialdom’s cold shoulder has not caused Mavrikos to abandon his historic mission, however. “I still get a thrill from making important finds,” he confides. “Just a few months ago, for example, I came across a packet of hand-painted post cards from the Italian period, one of which shows a huge cross which used to stand on a mountaintop at Filerimos, until it was destroyed during World War II by the Italians who feared it showed the RAF the way to the military airport.”

The Italian post cards also depict such scenes as the arrival of General Ameglio and his 33rd infantry regiment in 1912, the parade of his troops through the heart of Rhodes city, and a military deer-hunting party in the mountains of Profitis Ilias.

It’s the human side of collecting that motivates Mavrikos to keep traveling around the Dodecanese islands each winter and to stay in touch with a network of friends in Turkey, Italy and England who search out artifacts for him.

“Two Lindian brothers came from Canada a few years ago,” Mavrikos says by way of elucidation. “They wept when they say a photo of their father taken in the 1920s in front of the family house.

“Later, one of the brothers asked me how I could live like this, in a house filled with all these memories. I had never thought of it like that,” Mavrikos admits, “that all these bits and pieces had memories attached to them, memories that had real meaning for people today.”

Mavrikos collection is presently stored in a corner house on the main square of Lindos, the former site of the Albergo Italia, cafe and Ristorante, during the Italian occupation of Rhodes.

“The Albergo was run by my grandfather Dimitris, who had also lived under the Turks and given me many kinds of memorabilia from those days post cards showing the Turkish quarter of Rhodes, newspapers from the period, a land deed dated 1897 with Turkish stamps, signed by the Mayor of Lindos.

“My mind stopped when I saw the deed. It was incredible to think about it – the history that I was holding in my hands, a piece of paper that many people would have thrown away. I felt like an archaeologist who has been digging for months and finally unearths something wonderful,” Mavrikos recalls.

Being the guardian of such rare and important historical artifacts gives additional urgency to Mavrikos’ desire to find a public showroom for his collection. “These are things our children must be able to see because, if they can’t, they will never know what the island was like in the past and how it was to live here,” he says.

Mavrikos hopes that a historical society or charitable foundation will materialize one day to either fund his museum or publish a book illustrating items from his fascinating and unique collection.