Some museums, like wines, grow better with aging. Not only do they become richer in content but their material in time acquires greater preciousness. This is particulary true of collections which relate to a country’s traditions and its folklore. Certainly this is the case with the Museum of Greek Folk Art situated in Plaka, right in the heart of old Athens. The museum is celebrating its 70th anniversary this year.

Strolling up the pedestrian walkway of Kydathinaion Street, the unsuspecting passerby can have little idea of the treasures that lie just behind the plain, unprepossessing facade of a three-storey building standing opposite the church of Ayios Sotiris. The only hints are a small plaque bearing the museum’s name and some posters pasted up to the right of the entrance.

During visiting hours the main door is always wide open and the smiling faces of Kyrios Leonidas, one of the guards, and that of Kyria Kaiti at the small information booth, establish at once the friendly atmosphere of the place. This informal hospitality radiates from the museum’s dedicated director, Eleni Karastamati, and her hard-working young colleagues.

As an example of this informal cheerfulness, take a recent musical event, played live on traditional instruments, which included popular folk pieces from all over the country. Members of the audience joined in the singing as they ambled around and were offerd mezedes prepared by a country woman from central Greece and wine which flowed a gogo. From the old neighborhood lady who escapes here from lonely evenings at home, a pair of young Japanese tourists and a family accompanied by their children to people who reminisce together about their youth in a small village and the expert specialized in some field of anthropology the museum’s ‘open houses’ gain their kefi, their cheerful mood.

The Museum of Greek Folk Art came into being as a result of The Return to the Roots’ movement which swept through Athenian society around the time of World War I. Before that, Athenians looked back on their folk traditions either in shame or with contempt.

Among the leaders of this movement were the writer and poet Periklis Yiannopoulos, architect Aristotelis Zahos, and the pioneer folkorist, Angeliki Hadzimichali. Fortunately, the poet George Drossinis headed at this time an important department in the Ministry of Education and he initiated the reopening of the abandoned Tzisdaraki Mosque to displays of folk art. Its organization was given to Anna Apostolaki who, despite public indifference, safeguarded and augmented the collections put into her hands for 30 years.

It was only after World War IΙ, however, that the museum reached maturity, and for 25 years Popi Zora can be said to have been its soul. In short, she turned a warehouse into a museum.

“When I took over the directorship in 1953,” says Mrs Zora, now retired, “there was an enormous amount of bric-a-brac, most of it foreign. There was, for example, an Empire coffee set donated by a Danish collector, a small library of French literature and Coptic textiles.”

Starting with a hundred Cretan embroideries which Apostolaki had acquired on her native island in the 1930s, Zora decided to transform the material into a purely Greek collection and eliminate everything else.

“Apostolaki was an exceptional woman. Many of the museum items she had paid for with with her own money. At the time of her retirement I was graduating from the Faculty of Archaeology at the University of Athens and was dreaming of becoming a Byzantinist. But I decided to try everything to secure Apostolaki’s vacated position, and I succeeded.”

The mosque had at one time been used as a prison and that dismal atmosphere had never quite been dispelled. For two years Zora dusted and cleaned ,the items, put in running water and installed a bathroom. In 1959, the renovation was complete and the institution opened its doors to the public under its present name.

Because rural folk had come to despise folk art, gypsies would buy the contents of whole country houses by the oka — the standard weight of the time — and hawk them on the sidewalks of the Flea Market in Monastiraki. Rummaging through these heaps, Mrs Zora came up with treasures: costumes, embroideries, utensils, jewellery and furnishings.

Although the funds of the museum remained modest, Mrs Zora was able to add objects from more sophisticated markets. One of these was a boutique, in Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, owned by Joseph Soustiel, whose forebears had been wealthy Jewish merchants from Salonica.

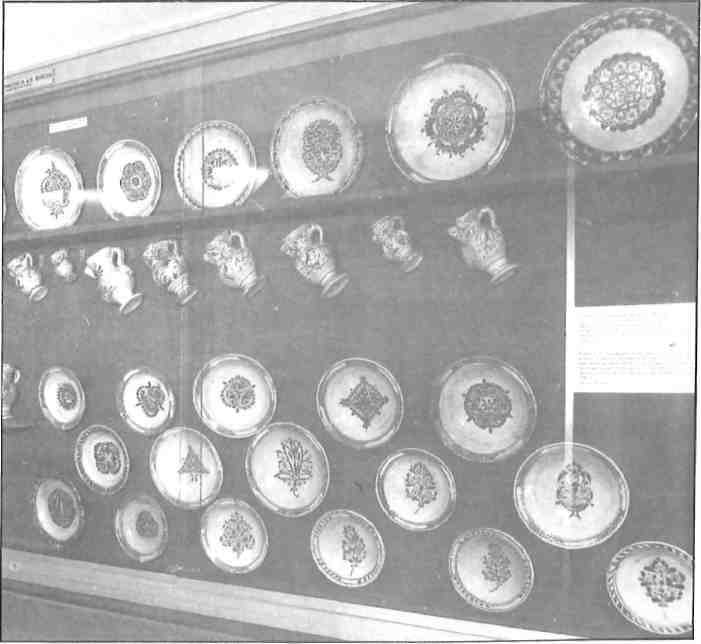

Another source of supply were the previously well-off families who had been forced to leave Egypt when Nasser came to power in 1956. About 200 magnificent national costumes were acquired at this time, as well as the unique Vassilis Kyriazopoulos collection, comprising 600 ceramic objects. In two decades Mrs Zora built up a total of 12,000 items.

While the mosque was picturesque, it no longer had the space to show these. large quantities of objects. The exhibits became cramped and the personnel felt suffocated. After years of house-hunting and flirting with the idea of acquiring some fine old neoclassical house, the decision was made to move into the present premises. This utilitarian building had been built as a nightclub with offices above, but its layout had possibilities and above all it was spacious: 1200 square metres compared to the 150 square metres of exhibition space in the mosque.

In 1972 the new museum was inaugurated. In it a workshop for restoration and conservation had been set up employing specialists, and teaching students the science of preserving popular art and folklore. This led to the first mobile exhibition of crafts which went around to nine countries, mainly in Europe.

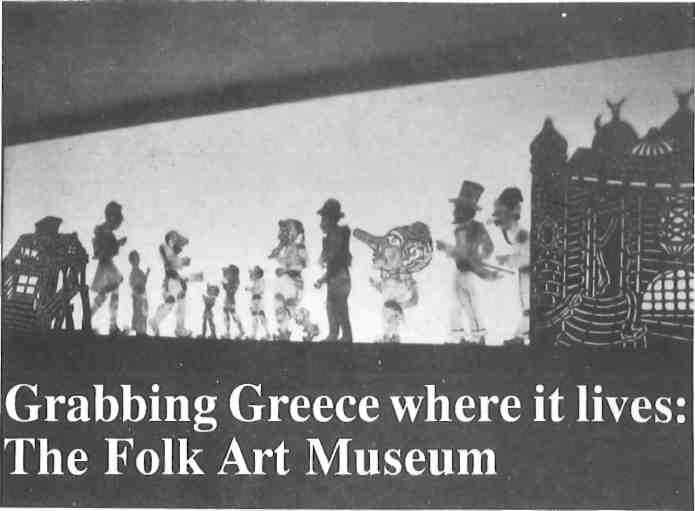

In 1981 the first Karaghiozis shadow theatre perfomances took place at the museum and then travelled all about the country. Today, a specialized library contains 3000 books, and a photographic archive has been set up along with documentary videos of traditional festivals.

The third woman in the museum’s life and its present director, Eleni Karakatsani, is young and eager and she is the one who has given the institution its modern, up-to-date air. “The idea of presenting items one by one, as pieces of art, and displaying only well-conserved examples while setting aside used or damaged ones is not the contemporary concept of museology,” she explains.

“Today, each item is presented in its overall environment, in its context of use. In this way it comes alive, appeals to the visitor and is educational all at the same time.”

The museum’s most recent renovations have introduced both didactic flavor and a certain aesthetic charm. In the basement there is ample lecture and projection space. The ground floor is given over ot the museum’s remarkable collection of embroideries from all over Greece, particularly the islands.

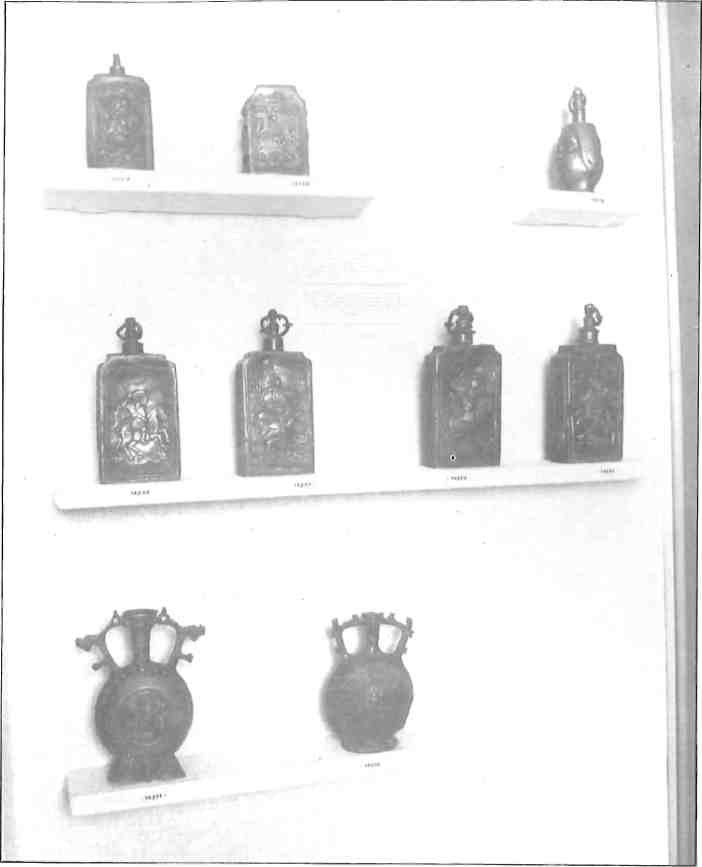

On the mezzanine is a collection of ceramics recently donated by Efi Micheli, masquerade costumes, wood carvings, as well as the puppets and construction materials from the Karaghiozis shadow theatre.

The floor above contains more embroideries and many frescoes and paintings by Theophilos (1867-1934), the most celebrated of Greek naif artists.

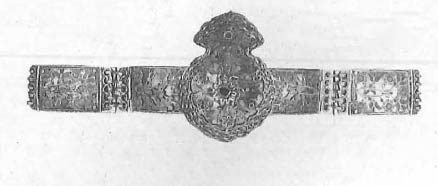

The second floor is devoted mostly to jewellery and ornamentation of gold, silver and precious stones. Some are ecclesiastical, some decorative. Photographs beside the exhibits help to explain them, The texts describing the various techniques of casting, filigree, enamelling, embossing, et cetera, are detailed and concise at the same time. There are headdresses, crosses, amulets, buckles, belts, breast ornaments and talismans. There are, as well, special sections devoted to ex votos and to weaponry.

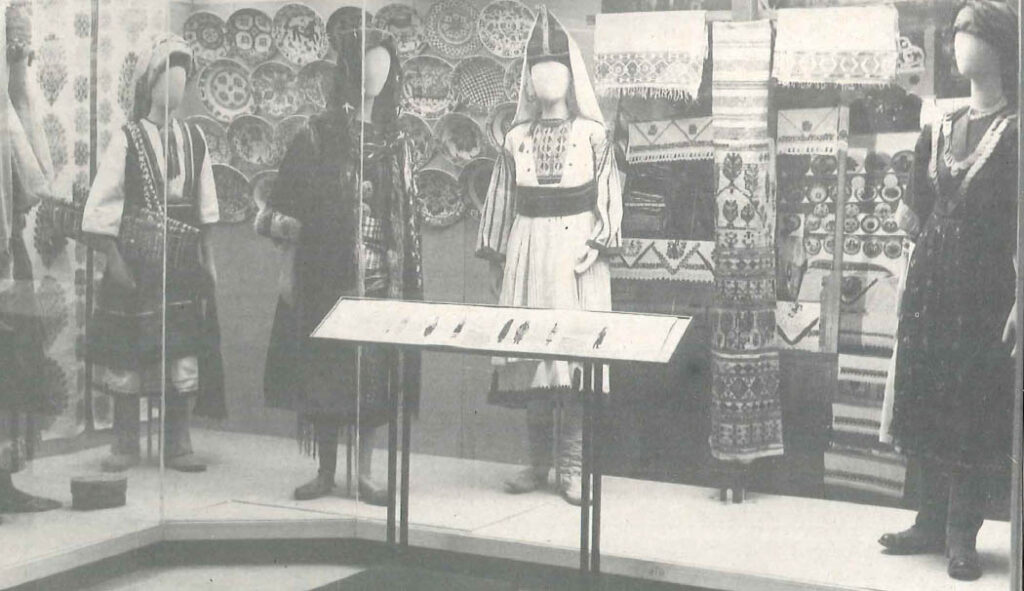

On the top floor are vitrines displaying mannequins of men and women in full regalia, with maps identifying the provenance of the costumes and explanatory texts in Greek and English. In a corner on this floor a group of ladies may by found practicing the art of stitchery. Once a week, in collaboration with the Centre of Asia Minor Embroidery, Vasso Argentou leads a class in this handicraft free of charge.

Because visitors, and especially children, who have all been brought up with television, have a strong audiovisual bent Mrs Karastamati employs recorded popular folk music and takes the greatest pains to project the most attractive displays.

Since 1983, the museum has systematically introduced programs directed towards children and students as well as foreigners. For children, seasonal events are organized, especially at Christmas and Easter, with songs and music and dance, along with educational aids to help them understand their traditions better. There are even special programs for the blind.

One of the most festive and popular events in recent times was the reenactment of a traditional marriage in all its details. Accompanied by music and dance, song and serving up of special local dishes, the ceremony was explained and its symbolism pointed out.

Mrs Karastamati is not only planning to expand museum space but envisions creating a traditional, early 19th century Athenian neighborhood with buildings in Plaka which the Ministry of Culture has offered. These include a Turkish bath, or hamam, and a three-storey pre-Revolutionary building.

Meanwhile, constant efforts are being made to augment the collections. One way to achieve this is to foster exchanges with other museums. In this way the 600-piece collection of jewellery donated by Angheliki Hadzimichali was acquired from the Byzantine Museum.

“Our staff is overworked and make huge personal sacrifices,” says Mrs Karastamati. “All of them have studied the history of art or archaeology and have completed advanced studies abroad. But real expertise in folklore only comes with practice.” Echoing every museum director and curator in the world, she adds, “We need more hands and more money.”