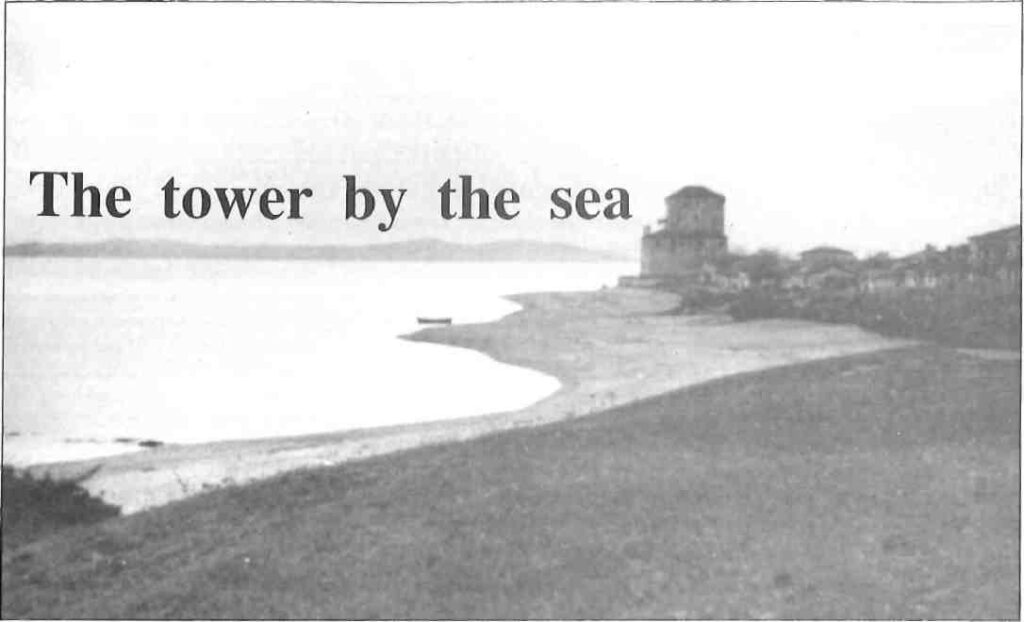

In recent years the great Byzantine tower rising from the beach at Ouranoupolis – still known by an ancient name, Prosforion – has undergone extensive repairs. So it may last another millennium. Built by the Emperor Andronikos II, the tower lies near the traditional frontier separating the monastic republic of Mount Athos from the rest of Greece. For much of the 20th century the tower was the home of writers Sydney and Joice Loch. They moved to the community in its formative years and are still remembered by many inhabitants.

Sydney Loch was born in London in 1889. At 17 he travelled to Australia and worked as a jackaroo at several sheep stations. He also tried his hand at pearling. In World War I he enlisted in the Australian Forces and participated in the Gallipoli landing. His first book, Straits Impregnable, is an account of that campaign. Contracting malaria, he convalesced for a long period in Egypt and then returned to Australia. There he met a high-spirited young woman, Joice NanKivell. Of Scottish and English origins, she had been born in Australia in 1893. There she had published a novel, The Cobweb Ladder, and a collection of bush stories, The Solitary Pedestrian. Sydney returned to London in 1918. Later that year, Joice followed on a troop ship, working as a journalist for the Melbourne Evening Herald. In 1919 they married.

In short order they set out for Ireland and lived in Dublin as freelance journalists during the last 18 months of the Sinn Fein War. They collaborated On a book, Ireland in Travail.

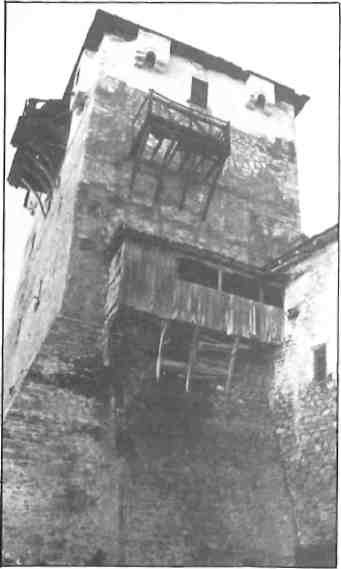

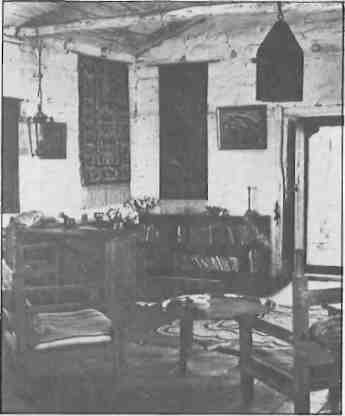

Though not Quakers, the Lochs enlisted in the Quaker Unit in Poland and from 1920-1922 served there as well as for a brief period in Russia. Then they came to Greece. By international agreement there was an exchange of populations following the war which drove the Greek army out of Anatolia in 1922. About a million and a half Greek refugees crossed the Aegean in exchange for a small number of people in northern Greece who considered themselves Turks. Many of the people moving into northern Greece had worked in Turkey as tradesmen or craftsmen and were now expected to earn their living by farming. The soil of Macedonia where they settled was poor and rocky and summers were dry. Much preparation of the land was necessary and therefore the Quakers had founded the American Farm School near Thessaloniki many years earlier. The Lochs came to work there in 1923. Sydney soon made the first of many visits to Mount Athos and both Lochs eventually fell under its mystical spell. The summer of that year they decided to live in tents on the small island of Amouliani just off the isthmus connecting Mount Athos to the mainland. About a mile away on the shoreline loomed an ancient Byzantine tower. Recently it had been deserted by the monks of Vatopedi Monastery and around it a new village was rising to house some of the refugees from Turkey. Many of its inhabitants were living in simple wooden huts or in tents. They lacked safe water, money and had no assistance in establishing their farms. The Lochs made arrangements to rent the tower and moved into a few rooms of the vast structure. The villagers helped them in constructing some simple furniture. Without really realizing it, the Lochs were becoming patrons, benefactors and physicians to the community. One of their first acts was to help destroy a wild pig which had been ruining the small rocky farms. Soon after they arrived, a young fisherman from the village crushed his hand between two fishing boats. With splints and bandages applied by the Lochs, he made a remarkable recovery. Within a short period, the Lochs began drawing other ‘patients’ both from the villages and monks from monasteries on the peninsula. Malaria was endemic to the area and the Lochs obtained an ample supply of atebrine to treat the disease. They also constructed a tank at the tower for raising gambuzia (a minnow-like fish that eats mosquito larvae) and gave numbers of these small creatures to people at monasteries situated near marshes. Joice often assisted in difficult births and together the couple treated many maladies of man.

The quietness of the tower provided a suitable atmosphere for writing. Sydney’s Three Predatory Women, a collection of short stories, was published in 1925. Joice’s The Fourteen Thumbs of St. Peter followed in 1927. For a number of years the village church was situated in a room on the top floor of the tower. The priest, assigned after settlement of refugees took place, had no salary. The Lochs provided him with a small sum each month.

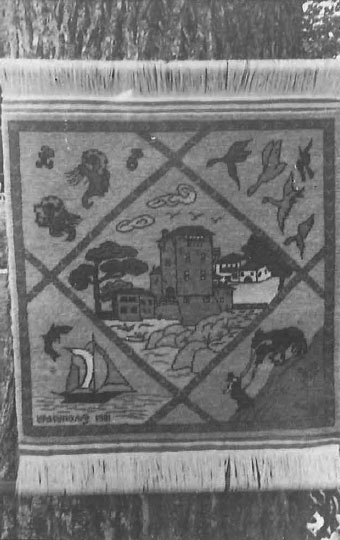

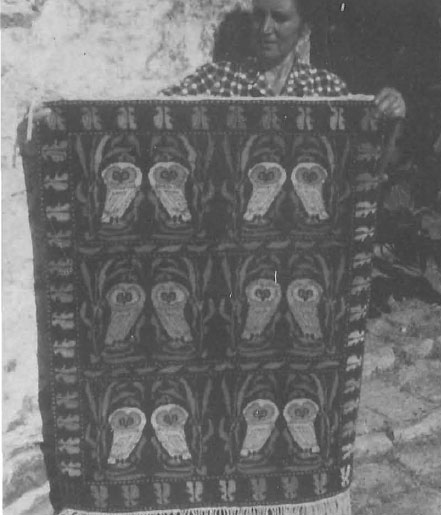

Some of the recent settlers at Ouranoupolis had worked in Turkey manufacturing carpets. They had become accustomed to artificial dyes and Turkish patterns. The Lochs encouraged dyeing wool with natural and natively available vegetable dyes as well as using local motifs. Sydney sketched some from nearby monasteries, and this local craft was encouraged. When first exhibited in a competition in Thessaloniki, one of their rugs won first prize. The local villagers became enthusiastic and within a short time the Lochs turned over the carpet industry to the village. Today, rugs of fine quality bearing Mount Athos motifs are still made in the village.

In 1932 a major earthquake shook the peninsula. Hardest hit was the village of lerissos to the north. Only hours before, a fleet of British warships had departed from Ouranoupolis, having left large crates of medical supplies with the Lochs for their dispensary. No road connected the two villages at the time. With the help of villagers the Lochs moved this equipment to devastated lerissos and began treating the injured. A day and a half later, the British fleet, hearing of the disaster, anchored offshore and provided food, clothing and other necessities. The Lochs and the fleet remained until the crisis had passed.

Sydney Loch explored the Holy Mountain of Athos frequently and became friends with abbots, monks and hermits. Since the mid-11th century women had been barred from the mountain. Many foreign travelers to and from the mountain were the Lochs guests.

During World War II, the Lochs left Greece and served under terrible conditions in the Quaker Unit in Poland and then Romania. They then returned to Thessaloniki and again began spending periods of time in the tower. This was 1945 at the height of the Civil War. The area was unstable and unsafe at the time because of intense guerrilla fighting. Sydney Loch worked from 1944-1951 for the British Military Liaison and at the American Farm School in Thessaloniki. By 1951, both Lochs were again living full time at the tower. Joice Loch’s Talks of Christophilos (1954) won a prize at the Children’s Spring Book Festival of the New York Herald Tribune. She used her prize money to pay for piping water down from unpolluted springs on a nearby hillside into the village of Ouranoupolis. She also purchased several Chiro sheep, donating most of them to local farmers to establish flocks. A visit from the Oxford Relief Committee inspecting the waterworks led to more interest in the sheep – and in turn more sheep were donated to the community. Animals, domestic and wild, played an important role in the lives of the Lochs. Turkish blue cats shared the tower with them. Many of the male kittens were given to the monasteries on Mount Athos to keep the rat and mouse population under control.

The Lochs were especially concerned that the increasing human population in the area just outside the confines of the monastic enclave was resulting in the decimation of wild animals. They nursed many injured ones and, when they were healthy, released them beyond the barrier of Mount Athos – a safe refuge. An injured baby owl with one eye became a favorite pet in the tower and lived with them for 12 years.

Sydney Loch died suddenly in 1954. He was working on the final draft of the manuscript of his book, Athos, the Holy Mountain. Joice completed the editing after his death and it was published in 1957.

Joice continued to live in the tower. Two of her long-term companions live in the village today. Her door was always open to travellers bound for the mountain. No fee was ever accepted. Although, as a woman, she was barred from entering the monastic enclave, she clearly fell under its spell. In 1959, she published another book for children, Again Christophilos, Her auto-biography, A Fringe of Blue, came out in 1968. Her Collected Poems followed in 1980.

Over a stretch of sea was the peninsula of Athos, and rising out of it a huge Byzantine tower, mystic, wonderful, gleaming blue-white in the full moonlight, or pink-stained white in the setting sun. A sentry on the land frontier of the Holy Territory. The tower fascinated us from the first moment we saw it.

Joice Loch

Infirm in her last years, Joice Loch remained in the tower until her death in 1982. She is buried in the village cemetery on the hill above Ouranoupolis. The remains of her husband, who had been buried at the cemetery of the American Farm School, were disinterred and placed beside her. The spirit of this remarkable couple remains very much alive in the village.

Conversations with Joice Loch by Tad Lonsdale

When we first came here, we found things in terrible condition. All arouind us refugees were dying from hunger and disease. Many of them had come from Caesarea, inland Turkey, and they had no idea how to live from the sea. The land here was granite-like and waterless. They found it impossible to farm. There were about 90 families, but many members had been lost or separated. They had no possessions. Many were suffering from malnutrition with big, bloated stomachs. Morale was low and they were desperate. They seized upon us to help them and wanted us to come and live in the tower.

The tower had then been abandoned by the monks, who, under governmental decree, gave the territory to the villagers. It was in a totally dishevelled state with mules and other animals using it as a stable. Sometimes the villagers themselves would pry loose some boards or some bricks for their own pitiful cement box houses.

For a while we could help the refugees with supplies from the Quakers and from work restoring the tower. We had to bring wood from Mount Athos and cut it into doorjambs, beams, floors, windows and furniture. We scrubbed, whitewashed and repaired the tower. Our friends began to visit and they too provided a market for the fisherman’s catch and whatever meager produce the villagers could grow. It was an awesome responsibility being the only people providing work, and as our own needs decreased we realized we had to find a way to make the people self-sufficient.

We learned that many of the refugees had been weavers back in Turkey. They made us some rugs but they were too bright and unmarketable. Then we hit on the idea to make only Byzantine designs. Sydney took photographs on Mount Athos of famous mosaics, frescoes, carvings and illuminated manuscripts. The monks were helpful and gave old copper designs to be copied. I transposed the designs to graph paper and we decided to make them in natural colors of sheep’s wool.

The villagers were horrified. They wanted to do them in their bright colors. But we insisted and commissioned the first lot. We sent them to be exhibited at the first International Trade Fair in Thessaloniki and they won the Grand Prix! The villagers were dumbfounded.

Soon orders began to pour in and we had a village industry going. But they wanted their colors and I was determined to do it by natural vegetable dyeing, Of course I knew nothing about it, but I experimented and finally through trial and error I found I could get 25 colors and shades from differnt boilings of different parts of the same plant! That rug went to the New York World’s Fair. King George used to collect my rugs at the Royal Palace in Tatoi and Hitler had one at Bertschesgarten.

The villagers set up the rug industry with a loan from the Agricultural Bank which provided looms, equipment and a workshop. Everything was fine until the War broke out and we didn’t get back here until 1949. And oh, my dears, what a horror! The communists had marked off the area. They’d shot many of the Resistance. Only Sydney was given a passport by both sides to pass safely through the borders. Others were only allowed to go ten miles. Those were terrible days. And we were heartbroken to return and see what had happened to the rugs. The villagers had gradually added acrylic dyes, mixed designs of different periods and sometimes even added a Turkish border!

You know, we’ve lived together so long we are like one family. We even have a family ghost, a friendly monk, whose bones are in a crypt in the tower. He often appeared from the balcony to wave at passing ships. But sometimes he was naughty, as when he teased the maid so often she went mad and danced naked about the tower. Regretfully, we had to exorcise the ghost, although when the maid also left he later returned.

You know, we had a vampire here who stole the bones of an unborn baby and put it in its father’s grave. I’ve delivered a hare instead of a baby, taken fish hooks out of eyeballs, sutured stumps left from dynamiting for fish, sewed up heads cracked in arguments.

Occasionally Sydney Loch, who was quietly puffing on his pipe, would interject, “Oh, Joice, I don’t remember it quite like that”