Photos by Hilary Sakellariadis

In the summer of 1841, a party of Athenians was attracted by the thought of mountain breezes and the pleasant pine forest, but the group was also hoping for a little fun with the eccentric Duchess of Plaisance, one of the notables of Othonian Athens. In his memoirs, the poet and diplomat Alexandres Rizos Rangavis describes setting off at sunrise from Athens with three companions. They had all heard of the duchess’s ambitious building plans, and hoped to have a look at her architect’s latest work, to poke a bit of fun at her behavior and enjoy a nice meal at her expense.

The carriage took two hours to reach the vicinity of the monastery in today’s Palaia Penteli. The travellers were longing for breakfast when they arrived, but they found the duchess was still asleep. The fresh air had given Rangavis and his friends a tremendous appetite, but when the duchess appeared she offered them nothing more than a healthful glass of Penteli water spiced with a few drops of lemon juice. Though they had great hopes of a midday meal, when the time came for lunch she explained to them that eating twice a day was unhealthy. So there was very little served, and Penteli water made up the greater part of the meal. Thus, they had to wait for dinner to ease their pangs of hunger.

Penteli was then so remote that Rangavis complained they could not even find a little honey to buy. They passed the day as best they could until dinner was served. But even then, one little hare was expected to feed ten hungry people, and the duchess’s dogs roamed threateningly around the table begging for scraps. A sliver of melon and a spoonful of sugar completed the meal.

At last it was time to leave and, always polite, their hostess accompanied her guests on horseback as they walked down to where their carriage waited. Needless to say, Rangavis and his friends stopped at Halandri, the first village they came to, and gobbled down bread and cheese.

The Duchess of Plaisance was tall and thin and given to dressing in flowing white robes. She had cut her graying hair and wrapped herself up in a white veil. Her dogs were famous for their size and the thickness of their coats. They accompanied her everywhere, some riding in her carriage, others running behind. Her many visitors were expected to wear white gloves if they hoped to please her. She was a grand but odd figure in Athenian society. Her only daughter, Eliza, had died while they were visiting Beirut in 1837, and unable to part from her, and perhaps fulfilling her daughter’s last wish not to be left behind, the duchess had Eliza embalmed, or rather preserved in spirits, and brought her body back to Athens.

Sophie dc Marbois was born in Philadelphia in 1785. Her maternal grand-father was William Moore, leader of the Pennsylvania Quakers. Her father, Francois Barbe Marbois, had been the French representative to the First Continental Congress, which met at Philadelphia in 1774. He had a distinguished diplomatic career and though he fell out of favor with Napoleon, he was rescued by his best friend, Charles-Francois Lebrun (1739-1824), the financial wizard whom the Emperor created Duke of Plaisance. His title came from the town ‘of Piacenza (or ancient Placentia) where Napoleon had crossed the Po during the 17% Italian campaign. Sophie married his son Anne-Charles Lebrun and their daughter, Eliza, was born in 1804. The marriage, however, was not a success, and after her father-in-law’s death, Sophie and her husband separated on grounds of incompatibility. They appear, however, to have maintained friendly relations: they exchanged letters and he may have visited her in Greece. He pursued a brilliant military career and died a few years after she did.

The duchess and her daughter were very close, and both were enamored of Capodistrias, attracted by his educational reforms and the romance of the Greek revolution. They soon became ardent philhellenes. Eliza donated her diamonds to the cause, and the duchess gave various sums of money, promising to support some of the destitute daughters of Greek revolutionary war heroes. The pair followed Capodistrias to Nauplia as soon as it was prudently possible, arriving triumphantly from Corfu aboard the brig Ares which Capodistrias had sent to meet them, commanded by a son of the great Admiral Miaoulis. The two adventurous ladies stayed in a small hotel in Nauplia, taking over most of its rooms and supplementing its furniture with their own.

The situation in Nauplia at the time was such that Capodistrias, who had brought his own furniture with him from Switzerland, gave orders to have it crated up again, lest he be thought too proud. The duchess soon fell out with him, finding him cold and arrogant.

She had meant to settle in Athens with Eliza, but her daughter’s death made all her plans meaningless. On her return to Athens in 1837, she set up house on Piraeus Street and placed Filiza’s coffin in a ground floor room, surrounding it with lighted candles and often visiting it to speak with her daughter. However, her energy was such that no matter how eccentric she became she could not stop organizing. Besides planning the education and care of the daughters of Greek revolutionary war heroes – she refused to help the poor, saying that she wanted to be generous but was not prepared to give charity – she engaged an architect to build her an elaborate townhouse in Athens, the Ilissia Palace, today the Byzantine Museum.

Together with her architect Stamatios ‘Cleanthes (traditionally named her architect), she visited Mount Penteli in 1840 to choose building materials. The ancient marble quarries had been left largely unworked throughout the 400 years of Ottoman domination until the Royal Palace of King Otto was begun in Athens in 1836. While visiting the quarries not far from Penteli Monastery, the duchess was inspired by the beauty of the surrounding countryside, and feeling the need for solitude in a country retreat, conceived the idea of creating a new ‘pleasaunce’ in Greece. She had her representative speak to the Igoumenos, or Father Superior, at once, with the purpose of buying monastic property.

Though almost all sources refer to Stamatios Cleanthes as the Duchess’s architect, recent research has revealed that Christian Hansen (1803-1883), a Danish architect resident in Athens at the time, may have been responsible for the design of the Duchess’s houses.

At the time the duchess was negotiating with the Igoumenos for her Penteli property, the monastery was very much in need of money to repair the damage incurred during the War of Independence. In 1839 the duchess wrote the following letter: “Having heard that the kaloyers of the Penteli monastery have debts and need to spend money for repairs on their buildings, I repeat the suggestion I made in person last year, that I acquire a certain extent of mountain land and water so that I may build our tomb (for myself and my daughter) and there build a castle (a country house) and plant gardens in this area which is so beneficial to my health…”

Internal politics and maneuvering over terms delayed the acceptance of her proposal, but with a good deal of pressure from the government (which was delighted by her promise to build roads and bridges), the land was finally sold to her. She agreed not to build walls around her property despite the bandit-infested area, but only around1 the garden of the ‘castello’ she intended to build. The borders of her land were to be marked by roads. The springs of running water were also to be left free to run down to Halandri, and to be available to the flocks of goats and sheep owned by the monastery. By 1841 work had started on the Rhododaphne Castello (named after the flowering oleander bushes in the area) and she had built the Maisonette, the smaller house where she stayed when visiting Penteli.

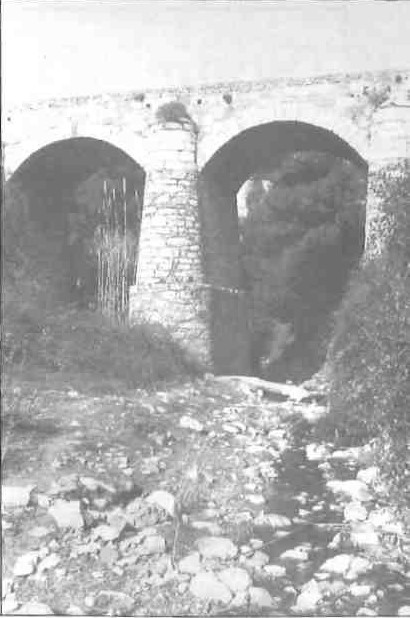

Many of the roads today between Nea Penteli and the old marble quarries and Palaia Penteli, as well as the main road between Halandri and Palaia Penteli, owe their existence to the duchess. A charming bridge in Melissia was built to facilitate the passage of marble blocks from the quarries to her Ilissia Palace in Athens. The bridge still exists today on a winding road that deviates from the main Penteli road and crosses over into Melissia, coming out on Halandriou Street. Some years ago there was a sign near the bridge, attributing it to Cleanthes. But Dimitris Kambouroglou, the biographer of the duchess, states that he*r roads and bridges were built by the engineer, Alexandras Yiorgantas. Today the “Bridge of the Five Arches”, as the sign in Melissia describes it, is as solid and attractive as it was 150 years ago, though the marble edgings on its parapet have disappeared. After crossing Halandriou, the road changes its name’ to Odos Palaio Latomeion, or Old Quarry Road. Here a jumble of winding streets leads one upwards alongside the ravine. The old church of Ayia Marina (near which the Marousiotes hid their famous miracle-working icon to preserve it from Turkish revenge during the revolution) is a dismal ruin today, but if one hunts one can find another small dirt road that winds down into the ravine, through the grove of plane trees, and across yet another small arched bridge, to lead up to the main Penteli road. Was this a section of the ancient winding road which the marble carts followed up and down the mountain?

In 1846 the duchess was kidnapped by bandits. Her kidnaper was the famous brigand, Bibissis, whose chief hangout was the Penteli cave with its Byzantine churches and spring of fresh water up near the ancient quarries. While driving up from Athens to visit her property, the duchess was waylaid by Bibissis, who had been hiding in the Ayia Marina ravine. He stopped her carriage and demanded money in return for her release. At first the duchess refused, and Bibissis threatened to kill her and her companions – her engineer Yiorgantas, and two or three others. As negotiations were going on, one of her companions escaped, or a foreman, coming down from the quarries to ask instructions, saw her predicament. In either case, someone went and warned the inhabitants of Halandri. They were very favorably disposed towards the duchess, who had built them a fountain and wash houses as well as the roads- which gave them access down to Athens and up to the monastery. Thus an armed band of men was soon formed, and together with some Marousiots, they set out to rescue the duchess. When Bibissis was warned of this, be let her go and escaped.

Poor Bibissis had an unfortunate end. The government paid another bandit to assassinate him, and his head was severed and brought back to Athens. They said of him that he never did anything wicked if he could avoid it, that he helped the poor, that the villagers respected him and that he had many friends in Athens.

A visitor driving up to Palaia Penteli today will notice first, on the right, before reaching the monastery, the huge, uncompleted stone building that stood at the entrance to the duchess’s property. Known as La Tourelle, this was intended as housing for her many workmen. It was started after her other buildings. Next to it is a small white house whose charming original design may still be seen despite later additions and alterations. The name “Plaisance” is engraved on a marble slab above the door. This was used primarily as a guest house. It seems the duchess would invite young married couples to stay in it. Somewhere in the meadow below these two buildings was a small lake she constructed called Thalassi, the little sea. Her biographer, Dimitris Kambouroglou, describes it lyrically, romanticizing the boat in which he spent hours floating about and dreaming. The daughter of a visiting philhellene, however, was very indignant to have made such an effort to get there, only to find it no more than ‘une grenouille de lac’!

The Maisonette, built in 1841, where she stayed whenever she visited Penteli, still stands entire at the top of the hill just beyond the monastery. It has been recently repainted and looks very handsome. An energetic visitor will want to walk around the garden to view its grand southern exposure.

The Rhododaphne Castello is beyond the square, a few blocks lower down and left, on the southern slope. It was built on a small plateau cut out of the mountainside, and thus it has a very cramped entrance for such an impressive dwelling. Gothic arches ornament it and windows pierce its severely neoclassical facade. The building is both romantic and serious, expressing the duchess’s yearning for a home that would reflect both her French back-ground and her tragic loss. It was never finished, remaining without roof or floors at the time of her death. The property eventually passed into the hands of the Greek government, and the castello was restored in 1957 by architect Aleko Baltatzis as a “gargonniere” for Prince Constantine. Though in a sad state of disrepair, the front courtyard of the castello is used for summer concerts and other cultural activities.

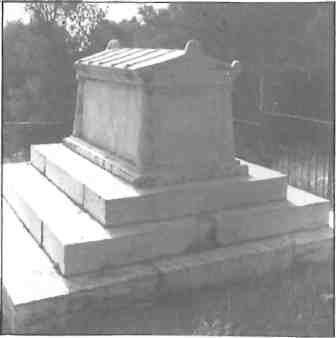

The duchess’s tomb lies just beyond the Maisonnette on the opposite side of the road. It was built after her death by the Skouzis family. Her close companion, Eleni Capsali, married George Skouzis in 1842, and he built the tomb and bought part of her property from her heirs. Her daughter’s name is not engraved on the tomb. The most macabre part of the whole story is that the duchess’s house on Piraeus Street burned down on 19 December 1847, and with it her daughter’s preciously preserved remains.

The explanation most commonly put forward for the fire was that it started from the candles surrounding Eliza’s coffin, one of which was accidently knocked over by a servant or by one of the duchess’s dogs. Whatever the cause, the house burned fiercely, particularly the room containing the coffin. The duchess lost all her possessions, and despite her appeals for help, no one could be found to save her daughter’s body. Perhaps the lead sarcophagus was too heavy? Thereafter she moved into the Ilissia Palace. Though her favorite residence was up on the slope of Penteli, her deteriorating health obliged her to remain in Athens, and she died there.

The duchess left no provisions for her tomb. She had once said that she would prefer not to be buried, but would like to be laid out in an airy open vault, with a bouquet of strong-smelling flowers on one side and a bottle of Bordeaux on the other, with some handsomely-paid shepherds keeping watch so that her body, in perpetuity, was not disturbed.