Major General Heiririch Kreipe was not having a lucky war. After two grim years on the Russian front, he was transferred to the command of the Irakleion district on Crete in the spring of 1944. The transfer was supposed to be a rest, but within weeks of his arrival he had been ignominiously snatched from under the noses of his own troops by a group of 11 Cretan Resistance fighters led by Major Patrick Leigh Fermor and Captain William Stanley Moss. After a grisly 19-day game of hide-and-seek with the occupying German forces, Kreipe was spirited off the island and taken to Cairo.

The kidnapping was a superb piece of morale-building theatre. Subsequent German atrocities in the Amari district were claimed by the enemy to be reprisals against those who had aided in the abduction. The evidence suggests otherwise.

What is beyond dispute is that the participants were and remain heroes to the Cretan people. Post-Cyprus revisionist historians, suspicious of all things British, have tried to devalue the operation. But a careful examination of the facts suggests that the atrocities would almost certainly have happened if the abduction had never taken place. The most romantic of novelists might have hesitated to create the two main characters involved. Patrick Leigh Fermor, whose evocations of Greece, the Caribbean and pre-war central Europe have made him one of the world’s great travel writers, has lived the kind of life most people can only dream about. At the age of 19, he walked across Europe from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople with little cash, his accommodation alternating between sumptuous schlosses and straw-covered outhouse floors. His friend, Sir Ian Moncreiffe, called him “a Byronic figure whose creative power is used to the full in splashing on to the canvas of his time the… colour of his own life.” He added that Leigh Fermor has a mind “as conscientious and thorough as it (is) fanciful.” Xan Fielding, another hero of the resistance, meeting him for the first time on Crete, commented on his “carnivalesque appearance” disguised as a Cretan, and added: “His conversation was appropriately as gay and witty as though we had just met each other, not in a sordid little Cretan shack, but at some splendid ball in Paris or London.” Even General Kreipe himself is quoted as telling Dilys Powell years later: “I liked Paddy.”

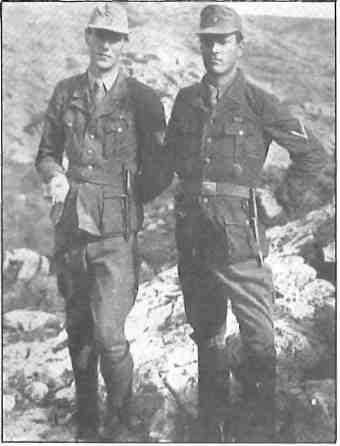

William Stanley Moss was hardly overshadowed by his charismatic collaborator. When war broke out, the 18-year-old Moss was in Stockholm, having left school not long before and gone to live in a log cabin on the coast of Latvia. He had found passage at last across the North Sea and joined the Coldstream Guards. Moncreiffe described him as: “Tall and devilishly languid, with that usual rather attractive droop of unaffected self-deprecation twisting the corners of his mouth”. After the war, Moss became a writer and married a Polish Countess.

In the continued absence of Leigh Fermor’s long awaited version of events, Moss’s “Met By Moonlight” is the only eye-witness version in print. The book was made into a film but Kreipe’s lawyers threatened legal action and neither book nor film was distributed in Germany. This is surprising because Moss seems to have liked Kreipe and his portrait is on the whole sympathetic.

These two John Buchan characters planned and successfully executed one of the most stylish and audacious missions of the war. Leigh Fermor, who dreamed up the idea of abducting a German general, was already in good training for the mission. During 18 months with the Cretan Resistance in the mountains, he had been responsible for spiriting the Italian General Carta off the island, though it is true he went willingly. Leigh Fermor had put up the idea to his superiors in Cairo on his arrival there soon after the Italian surrender and had been given the go-ahead. He met Moss two months later and the latter became second-in-command. The plan was to kidnap the German Divisional Commander and get him off the island at top speed, without bloodshed and without giving the Germans any pretext for reprisals against the local population. If things had gone entirely according to plan, the general would have been picked up from the south coast of Crete by the Royal Navy three days after his capture, leaving the Germans evidence from which it was hoped they would infer that the venture was the responsibility of a raiding party from the Middle East unconnected with the guerrilla forces on Crete. But it didn’t work out that way. By an appalling piece of luck, the Germans occupied the pick-up point, Sachtouria, on the night of the intended rendezvous. They had just learned of a gun-running operation there, so they burned down the village and garrisoned the ruins. The party decided to strike through the Amari mountains until they could find a point on the coast free of Germans.

The original target for the abduction was General Muller, commanding the 22nd Sebastopol (Bremen) Panzer Division. Subsequently executed as a war criminal, Muller had earned a fearsome reputation after a particularly bloody series of reprisals following an attack on a German post which led to the deaths of 100 enemy soldiers. The Cretans, among whom Leigh Fermor had been fighting for many months, longed for revenge, but there was always the problem of avoiding yet more slaughtered civilians and blazing villages. The plan, if successful, was to be bloodless. It would boost Cretan morale hugely and would remove Muller from the area. His replacement by Kreipe was a disappointment, but it was decided to proceed.

The Normandy landings were just two months away, and anything that caused the Germans confusion about when the second front would be launched was highly desirable. The Germans might well have wondered whether the operation was the prelude to an invasion. German morale generally would fall. As it turned out, the general’s aide-de-camp was arrested for incompetence, rumors circulated that Kreipe had engineered his own escape before an Allied invasion, and after the general was in Cairo, disgruntled search parties were still to be found in the inhospitable mountains of central Crete calling out “Kreipe! Kreipe!”.

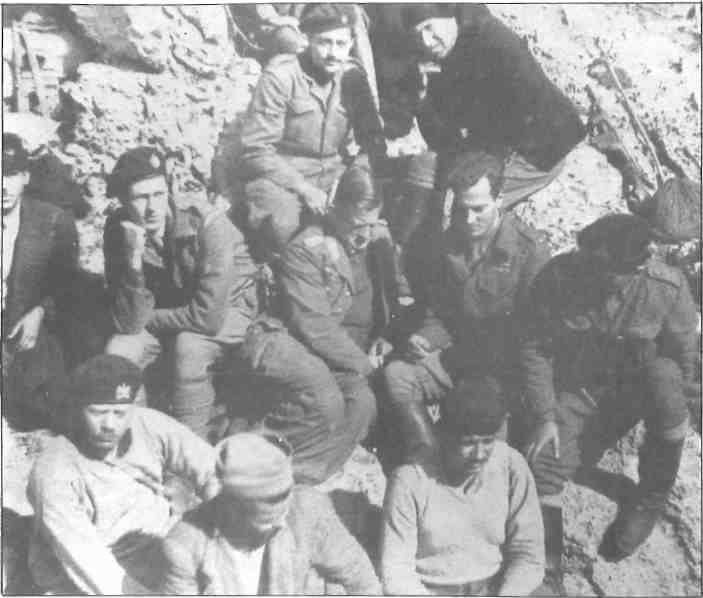

The 11 Cretan andartes who played a major role in the operation were handpicked by Leigh Fermor. They were close friends who had been with him on guerrilla operations and had proved their mettle. Since the operation is too often regarded as a two-man show with the Cretans as bit-part players, their names merit mention: Manolis Paterakis and George Tyrakis were the senior Cretans, tried and tested in action. They had accompanied Moss to Crete by boat after several parachute attempts had been aborted. Michael Akoumianakis had a house next to the Villa Ariadne at Knossos where Kreipe lived and was head of the Irakleion information network. He was assisted by a local student, Ilias Athanasakis. The oldest member of the party was Gregory Knarakis, a grandfather and veteran of many operations. Anthony Zoidakis was one of two policemen on the team. He was shot by the Germans a few months later. Anthony Papaleonidas also came back to Crete with Moss. The self-appointed cook of the party, he was “full of fun and story-telling”. Stratis Saviolakis, a local policeman, was able to spy out the land without causing suspicion. Dimitrios Tzatzas, a mountain guide to foreign troops, was quiet and reliable. Pavlos Zografistos had a house an hour’s march from Irakleion, where he accommodated the party while waiting for the operation to begin. When German soldiers came scrounging for food while the team was there, he dealt with the situation with cool courage. Nikos Komis, a shepherd from Thrapsana completed the party. Leigh Fermor has described them as “tough, experienced and fearless”.

General Kreipe lived in the Villa Adriadne, the house built by Sir Arthur Evans while he was excavating the Minoan palace at Knossos near Irakleion. The general was a career soldier rather than a hard line Nazi. He had won the Iron Cross at Verdun in World War I and the Knight’s Cross of the same order in this war. He was innocent of atrocities on Crete. The substitution of generals was fortunate for the whole party – they got on much better with Kreipe than they would have with Muller. One wonders whether the latter would have got off the island alive. Kreipe was battle-hardened and thus better able to endure the privations that would follow.

Every morning Kreipe set off in his staff car from the Villa Ariadne and drove to his HQ in the village of Archanes; every evening he drove back. Together with Micky Akoumianakis, Leigh Fermor, disguised as a Cretan, went to reconnoiter the route. It became clear that the villa was impregnable. It was surrounded by three rolls of barbed wire, sometimes electrified. The idea of using the general’s car surfaced at this point: wearing appropriate disguises and with pennants flying on the car, the team could drive through enemy checkpoints with ease, if not with comfort. Leigh Fermor seemed to enjoy taking risks for their own sake. An extract from a letter he wrote to Moss, waiting with some of the Cretans in a cave on Mount Ida, records: “I spent German Easter Sunday… with three German sergeants. We danced together and they embraced me drunkenly when we had to leave.” Micky had offered English cigarettes to the Germans, but managed to cover his gaffe by passing them off as captured booty bought on the black market. They also encountered the general himself in his car. They waved to him, and Kreipe, apparently pleased to get a friendly response from the local population, graciously acknowledged their greetings.

There was only one place suitable for the abduction, a ‘T’ junction where the driver would have to slow down and where ditches and embankments gave cover. The plan was for the English officers to dress as German military police to stop the car. “Paddy, much to his sorrow, was obliged to part with his moustache; but without it he looked so much the dashing Teuton that beside him one felt uncomfortably close to the genuine article. As for myself(Moss) …Paddy remarked that my appearance was that of an Englishman dressed as a German leaning against the bar at the Berkeley.”

The plan was put into effect on 26 April 1944, two nerve-wracking days after the date originally set. Kreipe would leave his HQ in Archanes around 8:30 pm each evening to be driven back to the Villa Ariadne. But the nonappearance of the general at the villa at the normal time would not immediately cause alarm because he sometimes stayed at Archanes to play bridge. The two Cretan intelligence-gatherers positioned themselves on a hillock 300 metres from the junction on the Archanes road. An electric bell was rigged up with a wire running from the junction to the lookout point, so the approach of the car could be signaled. Leigh Fermor and Moss, dressed as German police corporals, went to stand in the road with red lamps and traffic signs, signaling the car to stop. Kreipe usually sat in front beside the chauffeur. Leigh Fermor and Paterakis were to haul him out while Moss and Tyrakis dealt with the driver. Zoidakis, Komis, Knarakis and Papaleonidas were to handle any other occupants of the car. While the main participants were thus engaged, a secondary band of andartes was covering the roads converging on the junction, ready to hold up traffic during the kidnapping should it be necessary. Any occupant of the car other than the general was to be taken on foot to the rendezvous point on Mount Ida. Moss was to drive the car while Leigh Fermor sat beside him wearing the general’s hat. Paterakis, Saviolakis and Tyrakis would be in the back, keeping Kreipe hidden. Moss would drive past the Villa Ariadne, through Irakleion, then west along the coast. Near the mountain village of Anoyia the party would separate: Leigh Fermor and Tyrakis would take the car to where another road led to the south coast; the others would march south with the general towards the rendezvous point. An agent on Mount Ida would radio Cairo and the team would make its way to the south coast to be picked up by motor launch.

The first part of the plan went off smoothly enough. The car arrived about 9:30 pm, its two occupants, the general and his driver, were seized. The driver reached for his automatic and Moss had to cosh him. Within a minute of its departure from the junction, the car passed a German troop convoy coming the other way. The drive towards Irakleion was a heart-stopping one: the party had to bluff its way through no less than 22 checkpoints. At the first, the car slowed down to give the sentry a clear sight of the general’s pennants on the wings, then Moss accelerated away, expecting at any moment to hear a rifle shot. But the procedure worked and was repeated at subsequent control posts. They approached the Villa Ariadne, its gates open to receive the car. Moss blew the horn but didn’t slacken speed. The stickiest moment came during the drive through Irakleion. There was a garrison film-show in town and the streets were thick with troops. Moss sounded the horn imperiously and the soldiery scattered with hasty salutes. German habits of deference to authority were proving very useful. At the west gate the sentry stood firm in front of the car, which was compelled to stop. As the sentries approached the passenger side, Leigh Fermor called out that it was the general’s car and Moss put his foot down. Their luck held.

The general and the two British officers conversed in fractured French, the only language the three had in common. Kreipe was a classics scholar. He was fond of Horace and he and Leigh Fermor cemented relations later by capping quotations from the Odes. When the car party split up, Kreipe gave his word not to escape or shout for help if not treated as a prisoner. Paterakis reluctantly removed the handcuffs.

Later he took his promise back: “I rescind my parole. It no longer stands.” Leigh Fermor replied: “Fine, Herr General. We must look out.” The matter was not mentioned again, but both sides continued to behave as if the parole still stood.

While three of the party escorted the general to the village of Anoyia, Leigh Fermor, who could scarcely drive a car, drove on with Tyrakis towards the road leading to a submarine beach on the south coast. The car was abandoned at the junction. In it were left a commando beret and a packet of Player’s cigarettes, to reinforce the idea of a raiding party. Also left behind was a letter to the Germans, making the point again that the only Cretans to have been involved were regular members of the Greek Army who had come in with the raiding party.

The day after the abduction, a spotter plane dropped leaflets threatening the direst reprisals against the “rebel villages in the Irakleion district” if the general was not returned within three days. The threat was not carried out.

The party, reunited on Mount Ida, located an SOE radio operator, but the set broke down, so the only option was to send runners to agents in other parts of the island so Cairo could be notified to pick them up. Meanwhile the Germans, apparently not fooled, were closing in, while the party scaled Ida to descend its southern slopes before a ring of steel could be cast around the mountain. On 3 May, they learned that 200 Germans had occupied the beach they were to have been picked up from.

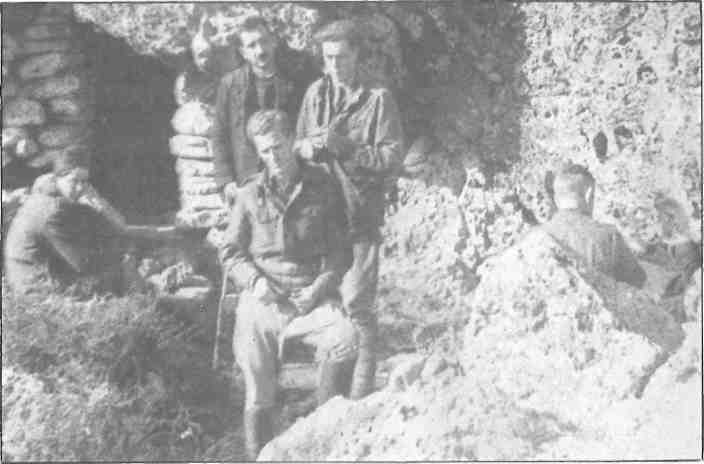

There followed many days of acute privations: night marches across some of the most difficult terrain in Europe, days hiding in damp ditches as the rain fell, concealment in tiny caves where sleep was impossible, cold, fatigue, sickness, hunger and constant anxiety. It was bad enough for two tough young commandos and a handful of hardy Cretans: for a captive with an injured leg, approaching 50, it must have been a nightmare.

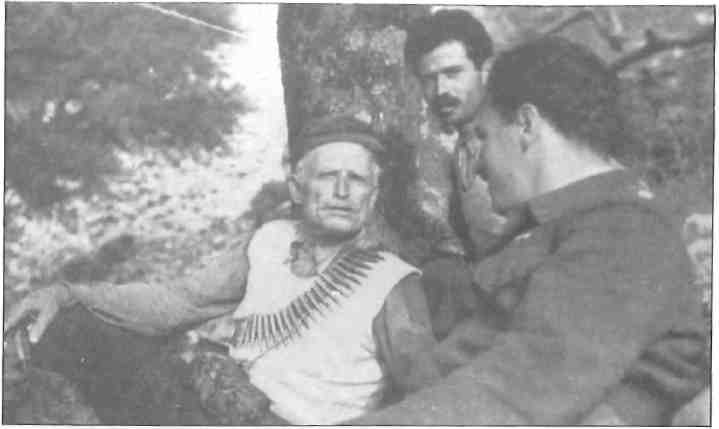

As time passed, a burgeoning friendship was observed between the general and Manolis Paterakis, a key man in the team and described by Leigh Fermor as “my guide, philosopher and friend for over two years”. (Kreipe and Paterakis greeted each other warmly on an astonishing television program first broadcast on 2 May 1972. In this program, a sort of Hellenic “This Is Your Life”, all the surviving abductors met Kreipe in an Athens TV studio. This risky venture was a great success, ending up in a private taverna banquet. For months afterwards, all the participants, when dining out, were inundated with jugs of wine from neighboring tables.)

Leigh Fermor went off to locate a radio, while Moss, Kreipe and the Cretans moved west, parallel to the south coast. An intended Allied rescue mission to the occupied beach was headed off. Leigh Fermor rejoined the party. German search patrols remained a constant threat, with more than one near miss. Scouts were sent to find a suitable, unoccupied embarkation point. Every member of the party suffered illness or injury along the way. The general had the misfortune to fall off his mule. At last a rendezvous was arranged on Rodakino beach. A forced march got them there in time and they were taken off without a hitch. Against all odds, they had succeeded. It was 15 May, 19 days after the abduction.

A month later, Moss was back on Crete. The British had honored him with the Military Cross, the Germans by putting a price on his head. Leigh Fermor was seriously ill for three months, but by October he was back, with a DSO: a similar bounty awaited any Cretan who turned him in.

Between 22 and 30 August 1944, the Germans went through Anoyia and the Amari villages with fire and sword. Leaflets dropped by plane gave as pretexts the harboring of ‘bandits’ and ‘Bolsheviks1; helping enemy troops, British spies and saboteurs, and the kidnapping of Kreipe, although the latter had happened four months earlier.

When Leigh Fermor returned to the region in October, he knew that the Germans had cited the abduction as a partial pretext for their atrocities and was not without apprehension. But the Cretans, resilient in the ruins of their villages, welcomed him back with open arms, dismissing out of hand the Germans’ claim that the abduction and the atrocities were connected. Since Leigh Fermor had a price on his head, it was natural for the Germans to try and discredit him, and indeed all the British . commandos, in the eyes of the Cretans. It must be significant that the Germans began their withdrawal to the area around Hania on 1 September, two days after the operation ended. The actions may well have been a preemptive strike, since these districts were on the Germans’ route to Hania. Previous reprisals had followed the event which was avenged with great speed. There had been serious clashes with German forces near Anoyia just 12 days before the reprisals began, with heavy enemy losses. The German policy had always been the ‘execution’ of ten Cretan civilians for every German soldier killed. The Amari was a regular hotbed of Resistance activity.

From the end of the war until the Cyprus troubles soured relations between Greece and Britain, the Greek attitude towards the abductors was unambivalent. Leigh Fermor was made an honorary citizen of Irakleion, his citation referring to his “scrupulous care… to avoid reprisals on the Cretan population”.

After the Cyprus troubles began, Greek propagandists used any stick that could be pressed into service with which to beat the British: the abduction had ‘provoked’ reprisals. In the light of the stubborn and mistaken British behavior over Cyprus, it is perhaps hard to blame the propagandists.

In October 1955, a British Embassy official visited Crete, having taken the precaution of arming himself with a letter of introduction from Leigh Fermor. Hostility against the British was great in the mountain villages and it was made clear to him on more than one occasion that had he not been a friend of Leigh Fermor, unpleasant consequences might have ensued. The letter, when used, was greeted with enthusiasm and became a passport to warm hospitality. It is clear that attempts to link atrocities to the abduction fell on deaf ears in Crete.

A citizen of Hania wrote to Dr. Gottfried Schramm, who is a leading expert on the Cretan occupation, asking him whether there was evidence of a link between the kidnapping and subsequent German operations. He replied that he could find none.

Forty-five years ago, news of this extraordinary exploit rang around the world. Crete remains proud of its sons, and adopted sons, who struck so shrewd a blow on behalf of a courageous and embattled people.