There are many ways of telling the story of a country. There are the facts, which are recorded in books, such as victories and defeats, the lives of great men, the reigns of kings, the clauses in peace treaties and the analysis of economic changes.

History can also be illustrated through crafts. When, in popular contexts, it is expressed with sentiment then we get to know intimately how people felt and thought about the times that came before them, and in the charming results we find the expression of values and of a tradition preserved with respect and love.

Can history, then, be recorded through 19th century stoneware dinner services? Of course it can, and an important part of it, too. Certainly one way to draw sustenance from a historical event is to find it emblazoned on one’s dinner plate.

Who began manufacturing history on dinnerware is anybody’s guess, but as far as modern Greece is concerned the French were early at it. When others were putting the ideals of Greek Independence into poetry the French were already putting them onto pottery. In brief, the best Greek Revolutionary ceramics are French and so it remained through the reign of George I early in this century.

Alas, pottery is perishable, and one doesn’t have to be a Greek nightclub addict to realize that smashability-by-night leads eventually to rarity-by-day in auction houses. There are individual French pieces of 19th century historical dinnerware that fetch 200,000 drachmas today.

A fine book on this subject is Angheliki Amandry’s The Greek Revolution in 19th Century French ceramics. She is a specialist and so is Vassilis Kyriazopoulos who is the founder of the folklore museums in Athens and Mykonos and the main source of information here.

From as early as the 17th century, it was the fashion in the days of discovery to decorate stoneware with the exotic landscapes and flowers, the architectural details and the leading personages of the lands and people the explorers came in contact with.

But it was only in the late 18th century that the passion for Hellenism began to take hold and it was intensified by the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821 and the shocking news of Byron’s death at Messolonghi three years later.

In Paris, the massacre on Chios inspired an exhibition of paintings on Greek themes which won fame for Gericault and Delacroix. The revenue earned from the Salon de Paris went to ransom Greek women and children held by the Turks. At the same time Chateaubriand published his Memorandum on Greece and Claude Foriel’s collection, Popular Songs of Greece, was followed by another by Nepomucene Lemercier. Meanwhile a Franco-Hellenic Committee was set up appealing to all Frenchmen to assist in Greece’s struggle for liberty. Concert and stage benefits were held and ladies of the French aristocracy went from door to door collecting money. In the mania for things Greek, Parisian dandies wore trousers of “Messolonghi Grey” and that tragic town gave its name to a popular new liqueur.

It is not surprising then, given the trend of the times, that potteries began manufacturing stoneware illustrating the events and leading personalities of the Revolution. These commemorative plates were enormously popular, and heroes like Kanaris, Kolokotronis, Markos Botsaris, Mavrokordatos and Ypsilantis literally became familiar household figures.

The leading manufacturers of dinner sets, illustrating what was known as the “Greek Affair”, were located at Choisy and Montereau near Paris and in Toulouse. The most popular sources for illustrations were the lithographs of Henri-Charles Loeillot-Hartwig, a German who spent most of his life in France.

The technique of illustrating on stoneware is know as transfer printing. After engraving the picture on a brass plate, the artist covers it with a special ink and prints it on thin paper. This illustrated paper is then attached to the ceramic item and baked in a kiln at a very high temperature. The transfer now takes place, as the ink pennetrates the stoneware. In the final stage the article is enamelled and fired again.

The greatest demand was for ordinary dinner plates, with a smaller quantity of serving platters, tureens, coffee and tea sets. The most usual scheme was black on a white ground but many came in colors. Although there was no number stamped on these pieces, making it impossible to calculate how many were manufactured, the seal of each factory determined its provenance.

Though some plates were octagonal, the great majority were round with the illustration set in the middle.

Klephts and armotoli, armed Souliots, riders, captured damsels, and scimitared Turks whacking fustanellaed Greeks were subjects most in demand although imaginary backgrounds of ancient temples and mythological scenes were popular, too.

The legend describing the scene, in French, appeared between the illustration and the decorative band at the bottom of the plate. This band came in a great variety of motifs. There were laurel wreaths, banners inscribed with the word ‘Liberie’, grapes and vine leaves, rabbits chased by dogs, fruits and nuts and floral designs.

Although the great majority of these plates were the standard designs mass-produced by the manufacturers, special orders for a certain scene or hero of the “Greek Affair” were filled. Among the collections of these rarities are those which Rene Puaux donated to the Antonouleion Museum at Pylos, the Ion Vorres collection at his summer home on Kea and that of Mr Vassilis Vitsaxis.

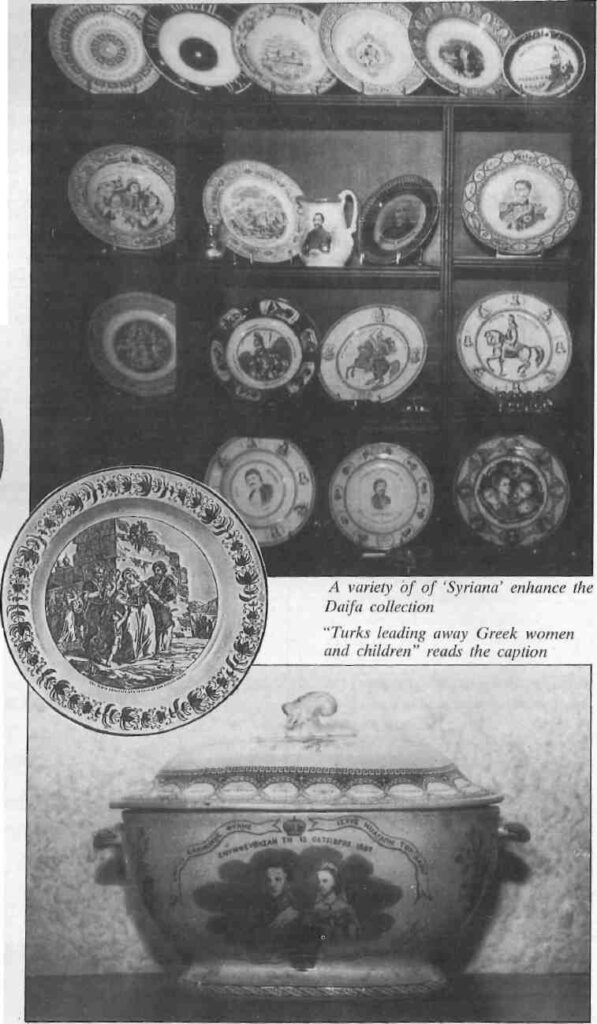

A whole other category of Hellenic stoneware is that devoted to the Greek royal family. Beginning with the accession of George I in 1863 this subject matter was popular down to our own day. Although the spirit of this art was as philhellenic and nationalistic as that of the earlier period, the clientele was more Greek than foreign and most of this stoneware was manufactured in England. Merchants brought these

items home in great numbers, and although there was a lively demand for them in Patras, Volos and Smyrna, the ware was collectively known as “Syriana” because the greatest number of orders came from the flourishing city of Ermoupolis on the island of Syros.

The earliest plates show George I, the young prince of Denmark, on his becoming King of the Hellenes at the age of 18. Four years later he fell in love with Sophia, the 16-year-old daughter of the Czar. Young, beautiful and infatuated with one another, the young couple returning to Athens from their marriage in Saint Petersburg so enraptured their subjects that seemingly endless stacks of plates were manufactured to commemorate the happy event. Inscribed in Greek with the words “Long live the King” and “They married on 13 October 1867”, plates depicting the royal couple bore prints in green, pink, black, blue and brown. The decorative bands were endless in variety but the most popular were wreaths of laurel with the names of the liberated areas of Greece and those still under Ottoman rule set into each leaf. A third, less common, scene is the royal couple at a more mature age, with a child between them, presumably the heir Constantine, Prince of Sparta.

In this heyday of plates commemorating ethnic events and aspirations, subject matter varied widely – from heads of Athena and Alexander the Great to those of Byron and Rigas Feraios, the poet-warrior; from allegorical scenes to the blowing up the Arkadi Monastery during the abortive Cretan Insurrection of 1866.

All these items were part of the decor of bourgeois interiors, set on stands and shelves as photographs were later. But, above all, they appeared at the dining table. “I would impatiently finish my soup,” Vassilis Kyriazopoulos recalls today, “so that with the last spoonfuls the horse of Kolokotronis or the face of Eleftherios Venizelos would be uncovered before my’ eyes at the bottom of the plate.”

The fashion for this kind of stonewear began to fade during the years between the world wars, and those converted to Venezelist liberalism gave their old ‘Syriana1 royalty plates to their servants as a part of their dowries.

Since World War II there have been a few brief revivals of this art. When Archbishop Makarios was exiled by the British to the Seychelles, His Eminence was portrayed against an exotic background of palm trees. King Constantine II and Queen Anna-Maria were popular on plates at the time of their marriage in the early 1960s. Later in the decade they were replaced by the portrait of the self-styled Savior of the Ethnos, George Papadopoulos.

There are passionate collectors of all these items today. Some plates are so rare that Mrs Lola Daifa, herself a collector, was offered a plate by a dealer so rare that he would only accept a two-room apartment in central Athens in exchange for it. In recent years, cheap reproductions of these plates have appeared on the market, and there is a danger that some are passed off as old, for they can be very cleverly antiqued.

In his superb home-museum in Paiania, Mr Ion Vorres, an affable host and passionate collector, tells how he acquired his extended accumulation of plates of all types and colors. At a time when people scorned or ignored them, he was picking up treasures for from 300 to 500 drachmas each. Today he has the largest collection of ‘Syriana* in existence, and many, such as the Arkadi Monastery platter, are very rare or unique. Altogether, the art constitutes a little known but exquisitely charming chapter in Greek traditional history.