By nine a.m., it was already hot on Laganas Beach, the sea as smooth as oil. A turtler strode up to the Turtle Information Station, unlocked the padlock and extracted the chain with a swift rattle. The station, made of unfinished wood, is stained a warm chestnut brown. Its straw-mat awnings shade the interested from the relentless Mediterranean sun while they ask questions about Zakynthos’ least understood visitors, Caretta caretta, the endangered sea turtles that visit the island’s beaches from June till August.

The turtler, Jason, unhooked and lowered three wooden flaps that form windows and when lowered display large blow-ups of the adult female loggerhead turtle and her hatchlings. A young boy dragged his father over, then begged him to buy a postcard of a hatchling entering the sea. The father protested mildly, but Jeremy’s curiosity triumphed.

Jason leaned out the window to talk with Jeremy, explaining that the single card of the hatchlings was sold out, but that Jeremy could get the poster of the hatchling, or buy the whole postcard set that tells the story of the nesting process. While Jason talked to Jeremy, the boy’s father’s reticence evaporated and he squatted down to look at the display posted at his son’s height. Turning he said, “Let’s get the whole set so you can tell your class back at school all about Greek turtles.” He went on to ask Jason for more details about his work there. Jason said he was a student from the University of Thessaloniki, though not, like many of the volunteers, a biology student. He started to explain about the Sea Turtle Protection Society of Greece, but Jeremy was impatient. The sand and sea were waiting. Dad introduced himself and said he’d be back in the afternoon. Jason encouraged him to return and urged him to read two brochures he’d just given him. The first one, Attention Beach Users, is essential reading and is widely distributed. The other is about the Sea Turtle Protection Society itself and is given to those who show a special interest: it includes an application blank for Supporting Membership.

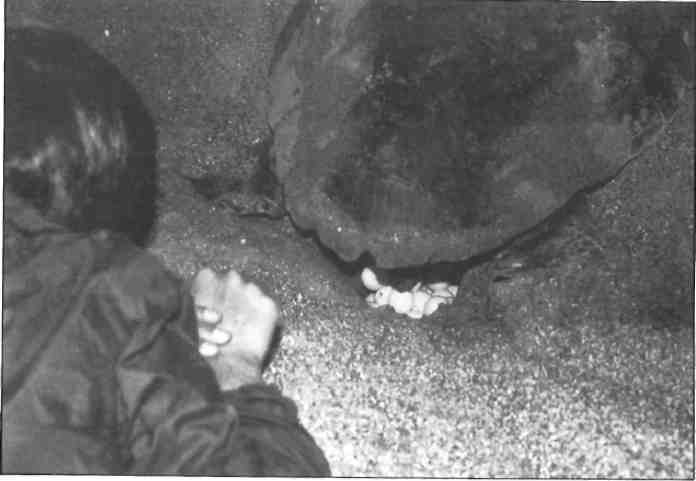

On this July morning, the first nests were just “bursting” open. The 55-day incubation period was up for the eggs laid at the beginning of the season, and it was very important that the turtlers patrol the beaches early in the morning to monitor the hatching activities. If they waited, the faint tracks of the young would be erased by beach users or the wind. An experienced turtler can count the number of tracks, and get a good idea of a nest’s productivity.

The turtlers also needed to determine whether any of the nests had been disturbed. Curious people sometimes try to probe around an unmarked nest to find a baby turtle, even help it to the water. Biologists believe that the hatchlings must find their own way to the sea, implanting in some yet unknown way their birthplace, so that they can return to these’ same beaches to nest.

Only too often, within metres of the nest, the early morning beach patrol finds dead, dehydrated hatchlings. Some are drawn inland by a bright light from a hotel; others get caught in a sandcastle moat that wasn’t leveled off. The earlier the turtlers get out on the beach to check the hatching activity, the better. Beach walkers seem to respect the markers that are set up at each new nest, and rarely does one find them disturbed. In fact, some early morning walkers like to attach themselves to the turtlers, follow along and learn. Most visitors don’t know that “emergencies” happen, and it is for this reason that nests are carefully marked, dated, and observed for the following ten days.

The morning patrol also has the discouraging task of looking for traces of illegal night behavior on the beach.

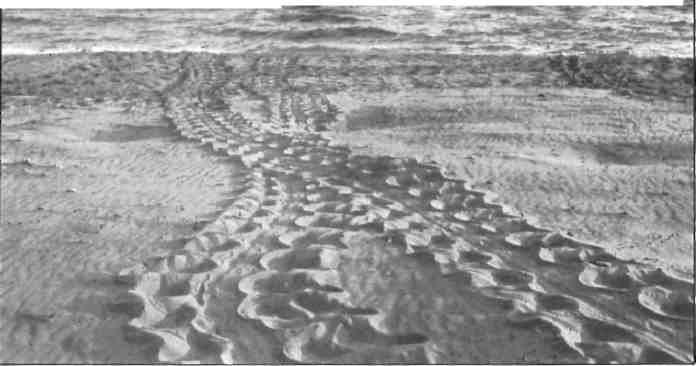

Thalia, Jason’s fellow volunteer, has walked the beach so many times that she feels she knows every sprig of dune grass, every piece of driftwood. She can spot the intruders’ tracks just about as easily as those of the turtles. Unfortunately the nighttime beach guarding system is not yet foolproof. On the day of Jeremy’s visit, Thalia once again found fresh horse hoof prints and at one point lots of new Moped tracks. The two kilometre beach has a number of entrances from the back road. Anyone living on Zakynthos soon learns that beach access is easy at night. This past year, Society volunteers undertook to share the guarding with the Prefect’s guards and there was some improvement. It takes Thalia about two hours in the morning to cover the beach, and that’s on a morning when few nests are “breaking”. A morning with ten nests can take up to three hours. This particular morning, she saw a jeep drive onto the beach, but it was too far away to get the license number. Guarding needs to be done on a 24-hour basis, and if all access is not restricted, any guarding system will be inadequate.

While Thalia filled in her observation report sheets, Jason distributed leaflets to swimmers and sunbathers. He tried to snare as many as possible of the stream of tourists pouring off buses. But among the visitors there are, too, the “regulars”, visitors who stop by the Station on their early evening beach stroll and who have “gotten into” turtles.

Jason and Thalia have often told other turtlers how many of these regulars have expressed their deep personal satisfaction with having learned so much on their vacation: Caretta caretta gave their trip meaning.

It is surprising that a small but steady number of people who are involved with the environment back home have chosen Zakynthos for their vacation specifically because of the turtles. Jason and Thalia agreed that it was a shame that the Society hadn’t yet found a way of conveying all this “tourist interest” to the Zakynthians. Two of them, along with the other 144 members of the society, were convinced that the more the visitors learned, either before or during their Zakynthos experience, the better they seemed to be able to accept the fact that the turtles -nesting females and hatchlings alike- need to be left alone.

In the late afternoon Jason was back on duty and true to his word, Jeremy’s father, Simon, came by to learn more about the society. Simon liked the word turtler, but he’d always thought it refer-red to the people who caught turtles, who went turtle hunting. He thought its new meaning was better and he wanted to know how the society had started and who its members were. Since Jason was a new member he said that it would be a good idea for Simon to talk with one of the founding members, two of whom would be by shortly. In the meantime, he could tell Simon about the toughest job of all, night monitoring of the beaches.

Monitoring includes tagging the nesting turtles or recording tag numbers if they are already tagged, measuring them, checking them for wounds, counting their eggs. Jason assured Simon that it is a taxing assignment. Zakynthian turtles are extraordinarily skittish. Turtlers have to wait for them to settle down and start laying before they can approach. For each nest, they may wait up to 40 minutes before tagging the mother. Nesting activity starts at about 11 p.m. and goes on till three or four in the morning. In addition to the tagging, turtlers have to convince curious intruders that their presence is illegal, that they are not permitted on the nesting beaches at night. After squirming around on their bellies for hours so as not to frighten the nesting females, the turtlers can really be pushed to their limit by a persistent illegal night beach visitor.

Simon, impressed by Jason’s dedication, asked how he could help. Jason said that maybe Simon could become a supporting member. At this moment Kostas came bounding into the station to do his stint, and Jason introduced him to Simon. Simon, intrigued by the self-assurance of the young volunteers, questioned Kostas about his involvement with the turtles. In turn, Simon’s sensitivity to the environmental problems impressed Kostas and Jason. They have found it hard to hear criticism that, while said in a polite voice, is all too constant, and often starts with prejudicial sniping at Greeks. Kostas and Jason, finding a kindred spirit in Simon, ask him about British environmental problems. The British tourist said there were many, and some of them never quite go away, like the problem of badger bashing.

While they talked, Kostas spied a boy of about nine dragging his mother towards the station. Quite obviously they had not come to the beach for a swim; the mother was wearing uncomfortable city shoes. The father walked obliquely away from the mother and son, exhibiting indifference. Kostas was quite sure they were Greek. The mother, trying to deter her son, said in a firm voice, “Yianni, that place is for foreigners, not for us Greeks.” Kostas, with a joyful chortle, boomed, “No, Kyria (Madame), this station is the essence of Greekness.” And as though speaking from a script, Yannis turned to his mother saying, “Ma, I told you, they’re our turtles.” Kostas turned towards Simon, translated and said smiling, “That’s really what the society is all about.”