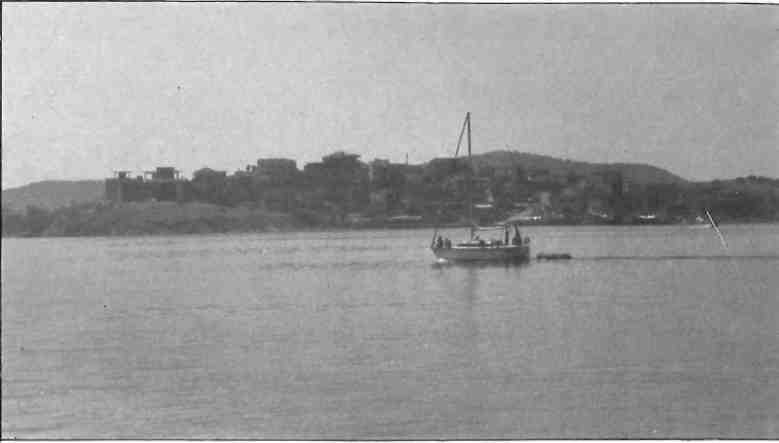

I caught my first glimpse of the tiny island village of Ammouliani as the bus from Thessaloniki careened around a bend in Halkidiki at a place called Tripiti.

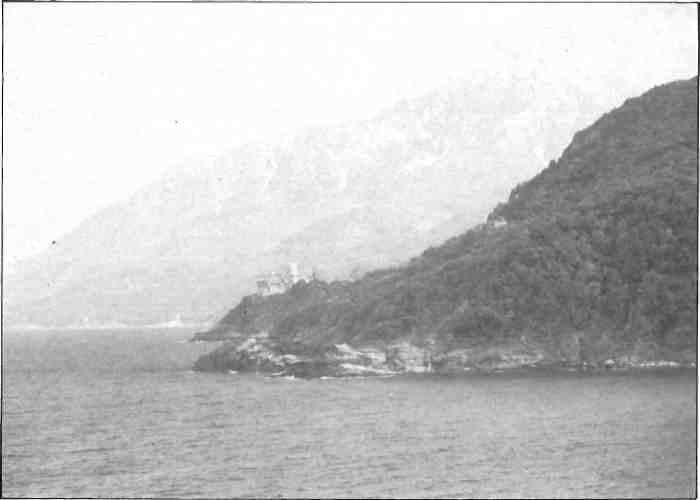

The name Tripiti comes from the Greek word for hole, and just prior to his leading the Persian army into Greece, Xerxes had a channel cut across the neck of Mount Athos for his ships to pass through. He then docked them in this northern corner of the Singitikos Gulf, just off the island of Ammouliani over which loom the heights of the Holy Mountain.

As the bus rocked to and fro, I could hardly have imagined what that sailing mirage of an island on the horizon would come to mean for me -then, a neophyte American anthropologist out on his first field study trip. It was 1972, and I would spend the next 16 months living on the island of Ammouliani with its Asia Minor refugees, suffering and celebrating all the vicissitudes of life in that lonely, isolated corner of remote Halkidiki.

It is difficult for lay people to appreciate the deep bonds of empathy that develop between an anthropologist and the people of the community he chooses to study from within.

There is no place to hide. You, the anthropologist, are clearly in the minority, the outsider, the total xenos, the alien dependent entirely upon the philoxenia – the hospitality – of your hosts. Do they want to be the objects of study? Do they understand why you are there? At times you too wonder why you’ve come, especially to a place like Ammouliani, with the winter coming on and the caiques no longer daring the passage to the mainland; when, as on Ammouliani a decade and a half ago, there was no electricity and precious few modern conveniences.

Herodotus, the ancient historian who recorded Xerxes1 great misadventure and his passage through Tripiti and sojourn at Ammouliani, was also the first true anthropologist. He provided the rationale upon which anthropology to this day is based. Unlike all the other social scientists, the anthropologist must infiltrate the alien country and find out for him/herself what and how these others think.

Herodotus expressed this in a single all-encompassing Greek verb: istoro -the cognate of the English word, history. I, alone, find out for myself: I am the story which I narrate. It was I, and I alone, who was there to witness these things which I now relate to you of these others. A bold concept, and one which continues to unite not just history and anthropology, but past with present: especially my own present, here in Xerxes’ hole!

But the people of Ammouliani were more than hospitable. They opened their homes to me and their hearts. They adopted me as if I were one of their native sons. Not only did I learn and record the secrets of their communal tragedy, how they lost their original patrida on the islands of the Sea of Marmara in Turkey following the defeat of the Greek army in Anatolia in 1922, but they shared their secret of survival with me as well.

While the story of the Great Catastrophe of 1922 was always alive with them, burnt indelibly into their memories, so too were their memories of resettlement. If they recalled the great loss and its incomparable shame and horror – the rout of the Greek army, the ensuing panic, the hordes of over a million refugees flooding every available Greek port in desperation, seeking lost family and friends – they also rejoiced in the bittersweet rewards of survival: of renewing life.

It is true that they lost their ancient homeland in Asia Minor; but, equally true, they built a new life in a new world. Greece had always been no more than a remote legend for them, a storybook land of gods and heroes. These simple fishermen and their wives and families, in all their humility, could clearly see that Greece, if she were to survive, depended on them, their own will to prevail, to resist the desolation of Hellenic culture threatened by the overwhelming Turkish onslaught.

There is a Greek song, released some years back, that admirably sums up their sentiment towards the history they lived through: “Romiosyne, Rorniosyne, den tha isihasis pia, ena chrono zeis irini kai trianda sti fotia! (Hellenism, Hellenism, you will never rest assured, for every year you live in peace you spend 30 in flames!)

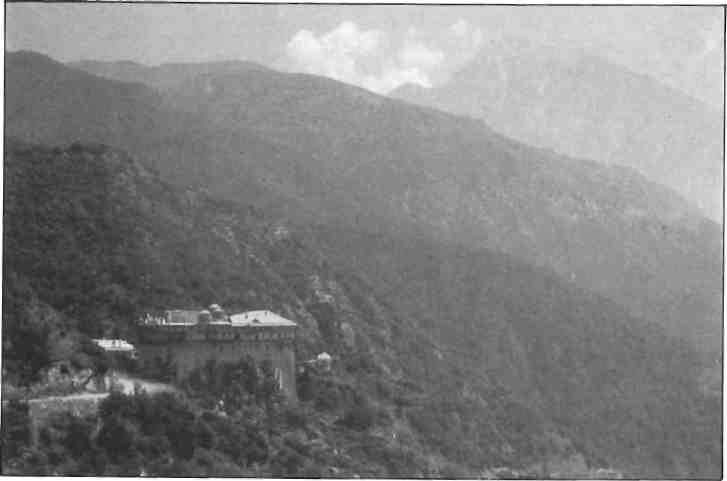

From out of these flames of destruction, these refugees of the Marmara islands built a refuge on tiny Ammouliani. The island was uninhabited when they came. It was attached to the monastery of Vatopedi on the Holy Mountain and it was all the bankrupt Greek government could afford to provide. They settled down in monkish seclusion – far from Athens, Thessaloniki, and their once beloved Byzantine capital, Constantinople.

They landed in the middle of nowhere. Joyce Nankivell Loch, a trained nurse and author of A Fringe of Blue, who, in 1926, settled across from Ammouliani at Ouranoupolis along with another group of refugees originally from the Princes1 Islands near Constantinople, related to me the horrifying hardships of the times.

‘They came with nothing but despair,” she once told me. “They were fishermen and they had no boats, no nets, nor any money to buy these things. They were sick with malaria. It was inconceivable how disconsolate they were – but it was even more inconceivable that they should still hope!”

Nor did they await a miracle at the threshold of the Holy Mountain. They took matters into their own hands. On this barren spot they would recreate their patrida: in fact, rebuild a facsimile of their lost homeland and continue its Asia Minor heritage in Greece. This was the secret of their survival, as I discovered during my months of research among them.

As they proved to me time and again, these refugees were a proud people. They chose purposefully to resettle in a place of their own rather than stay in Thessaloniki or Athens. They chose to remain together with their own kin, continuing their own communal customs, and to rebuild a community which they could call completely their own. They suffered as a result of their decision but they endured.

With no other resources but their native Asia Minor knack of building productive associations, they organized themselves into cooperatives, multiple family-based fishing companies, and set about exploiting the fertile sea that lay around their tiny, remote island. Soon they were manning their own crude fishing vessels, and, year by year, painfully building up a local economy of their own.

They started by bartering fish in the native Greek, inland agriculture villages of the area in exchange for the other essentials they needed to survive. And, eventually, with the slow accumulation of capital, they linked up with the markets in Thessaloniki and Athens. Of course, there were numerous setbacks in this painstaking process of self-propelled economic development but, decade by decade, the community advanced and eventually began to prosper. Thus they triumphed, maintaining their autonomy and their own traditional sense of community, against the overwhelming odds they faced as once destitute refugees.

Today, when I return to Ammouliani, like a prodigal son, arriving once again by bus past Tripiti, the island is no longer the remote place that I first remember. Nautical craft of every description, size and utility fill its neat harbor: car ferries, fishing trawlers, cruise ships and yachts. Electricity has come to the village and the fishermen are thriving off the burgeoning tourist trade which is growing by leaps and bounds in the area. Large hotels have sprung up in the vicinity and the island itself has become a favorite resort of the wealthy from Thessaloniki and is visited by myriad Italian, French and German tourists annually.

Nowhere are the scars of the past visible in the midst of this new prosperity; nowhere, that is, but in the memories of the refugees themselves who welcome home the once alien anthropologist, to whom they have entrusted their story of tribulation and triumph.

Professor Salamone’s story of Ammouliani, an account either life in a Greek fishing village and an Asia Minor refugee community, is published in English as In The Shadow of The Holy Mountain, The Genesis of a Rural Greek Community and Its Refugee Heritage , (1987), Columbia University Press; and in Greek as Ο Diogmos, (1989), The Free Press.