At first blush, the word “work-camp” seems to be a contradiction in terms. Camping is perceived by most of us as essentially a leisure pursuit that has very little to do with hard work- …once you get the tent up.

In the context, however, of the Intercultural Programs run by the American Field Service/Hellas, the term work camp means precisely what is says. These camps provide an opportunity for young people from all over Europe to live in often primitive conditions and work together on a specific conservation or restoration project which, last summer, ranged from repairing decaying windows in a village school to laying a traditional Byzantine pavement at an island monastery.

Camp coordinator, Eleni Gazi, first thought up the scheme four years ago after taking part in a work camp in northern Spain. Despite problems relating to poor administration and organization, she was very impressed by the experience of living with people of different nationalities and working to-wards a common goal. “The enthusiasm was tremendous. Nowadays, many young people are bored by the concept of a lazy vacation. They want to make a contribution to the environment as well as enjoy themselves,” says Gazi. The success.of the 1988 summer work camps in Greece undoubtedly bears out her theory. The first task, two years ago, was to obtain sufficient funds for the pilot project (the construction of an access path and a dry-stone wall near the shoreline of ). One hundred thousand drachmas were raised at an amateur concert at the Town Hall in Kifissia and, after applying to the Worldwide Fund for Nature and the European Commission, there was sufficient money to invest in essential tools and equipment. With the further support of the Elliniki Etairia, which provided tents and offered a suitable site near Lake Prespa at the Nature Observation Station, the first Greek work camp opened in July of 1987.

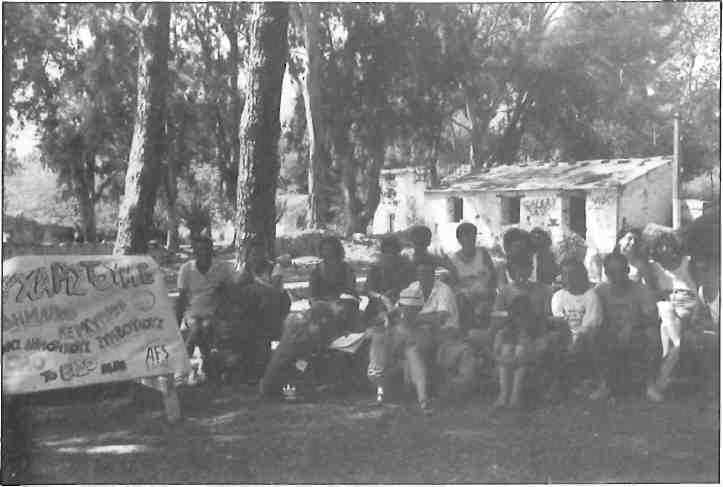

Although one of the chief aims of the work camp program is to make a contribution to the environment, equally important is the cultural exchange between participants and the promotion of a greater understanding of Greece, the country and its people. Camp workers are therefore requested to represent their own countries in a series of impromptu shows and presentations in the evenings, while lectures and day trips are arranged in order to introduce participants to Greek culture, landscape and traditions. These events are always highly successful and provide a welcome contrast to the five-hour daily work sessions which can be grueling, particularly for those who are not used to laboring in temperatures of around 30 degrees centigrade.

The success of the Prespa work camp, in which 11 campers from four different countries participated, inspired Eleni Gazi to expand her project to encompass three different camps of 20 members each, through the months of July and August 1988.

The first camp, at in Epirus, involved reconstruction and repair of the Paschalios School, part of a three-year conservation project designed to transform the derelict 19th century school building into a cultural and social center for the villagers of Kapessovo. With the cooperation of local architect Eleni Pangratiou and the Kentro Erevnon Zagoriou it was possible to determine what needed to be done in the first phase of rescuing the school building and its surroundings.

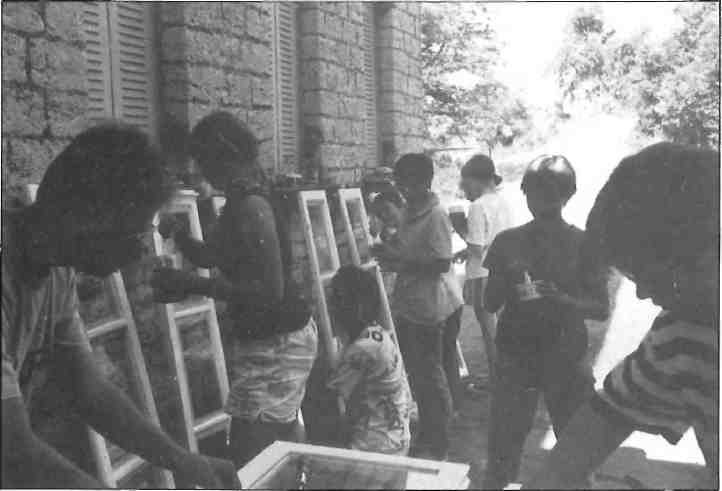

Initial work involved the repair of an old stone-paved path, rebuilding the original garden wall and clearing decades of undergrowth, as well as the more urgent task of restoring rotting window and door frames. Rudimentary dormitories were established in the classrooms and evenings were spent in the local taverna where, inevitably, native Greek hospitality and curiosity led to the establishment of warm friendships between the campers and village community.

Apart from learning about regional customs and traditional songs and dances, the participants also explored the surrounding region of Epirus in a series of excursions that took them through the Vikos Gorge, out to the ancient site of Dodoni and into the provincial capital of Ioannina.

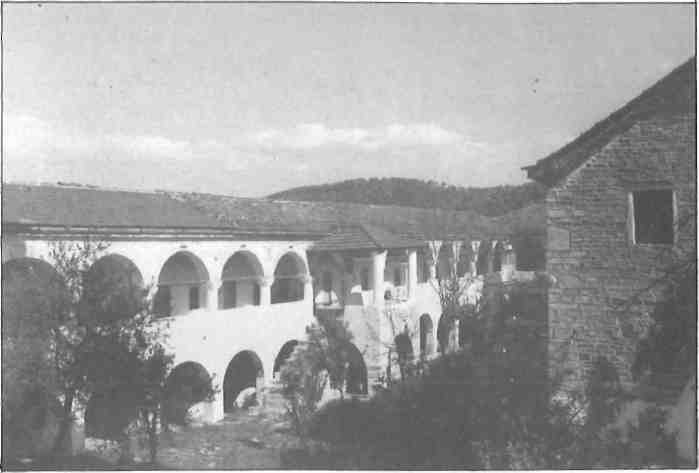

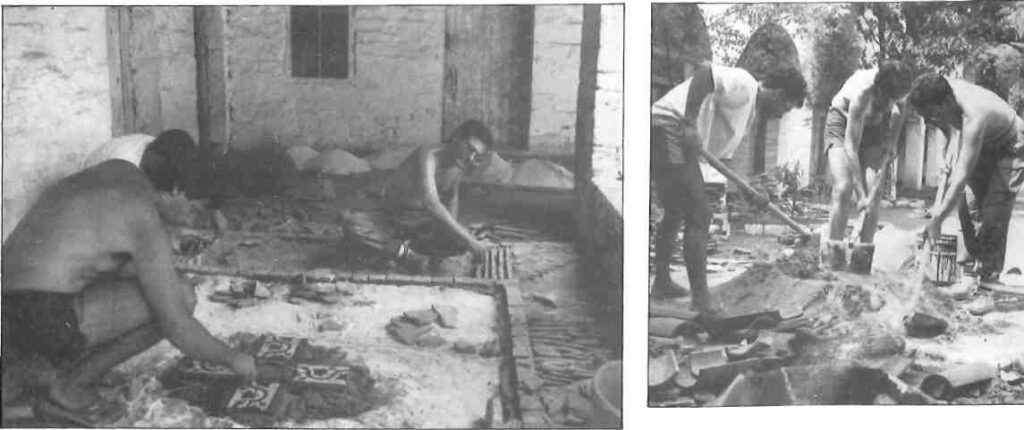

In contrast to the warmth and hospitality of Zagori, the second camp, which followed for 18 days in August, was located in a deserted monastery on the tiny island of Trikeri off the coast of Mount Pelion. Here all the campers’ enthusiasm and humor were needed to cope with primitive living conditions, drought and intense heat. Abandoned earlier this century, the Trikeri Monastery has been kept going largely through the dedicated efforts of Mrs Lena Koukiadi and a few friends. They needed help, however, with the physically demanding tasks of clearing tons of rubble from the central courtyard; repairing doors and windows and laying new pavement.

Under the guidance of architect Dimitris Galanos from Volos, the campers learned the technique of laying traditional Byzantine brick paving. Elsewhere, cells were transformed with whitewash, and paths were cleared of undergrowth. Excursions included visits to a neighboring monastery on a deserted island and a mainland tour of the city of Volos and the villages of Mount Pelion. Greek historian Thanos Veremis, who lectured at all three camps, gave talks on Greek culture and religion.

Despite many problems and a chronic shortage of water, Trikeri was undoubtedly the most successful of the three camps. Asked why, Ms Gazi explained, “We had a marvelous group of people from ten different European countries. They were not only particularly united as a team but also extremely cooperative as individuals.

Perhaps this unsolicited testimonial from a young participant from Iceland best expresses the unique spirit of Trikeri: “When I decided to come to Trikeri I was not sure what to expect, but the last two weeks have been far more wonderful that I ever dared hope. It proved once and for all that however different our countries and nations are, we are really the same in heart. I will always remember Trikeri.

The final work camp of the season, located on the Ionian island of Vido was sponsored by the neighboring municipality of the town of Corfu and here the task was to create a fire-break and cleat the forest of dense undergrowth.

Originally used as a harbor fortress by the British in the early 19th century, Vido was later designated a prison. The stone buildings are now derelict and the superb gardens, created by the British over a century ago, are sadly overgrown and neglected. With the ever-present risk of fire, the municipality enthusiastically welcomed the work camp initiative in helping with their fire-prevention program and were extremely generous in their support.

Now that the work camp project has been successfully established in Greece, Ms Gazi is looking towards the future. “This summer we shall have participants from the United States as well as from Europe and our projects will include conservation work in another village at Zagori as well as the restoration of the 19th century gardens at Vido.”

There is little doubt the 1989 work camp program will provide yet another example of United Nations activity at its best.