The temple site of ancient Rhamnous lies on the rocky terrace of a ridge overlooking the Gulf of Euboea. The coastline of the island of Euboea and its mountains, from Dirfy to Ohi 80 kilometres to the south, snow-capped in winter, are clearly visible across the narrow straits.

Rhamnous means “place of spiny buckhorn”, though little of the tenacious shrub is found here today. A forest fire devastated the landscape some ten years ago from the ridgeline all the way down to the sea, blackening hundreds of hectares of woodland. Today the area has grown green again and blooms with wild flowers in April.

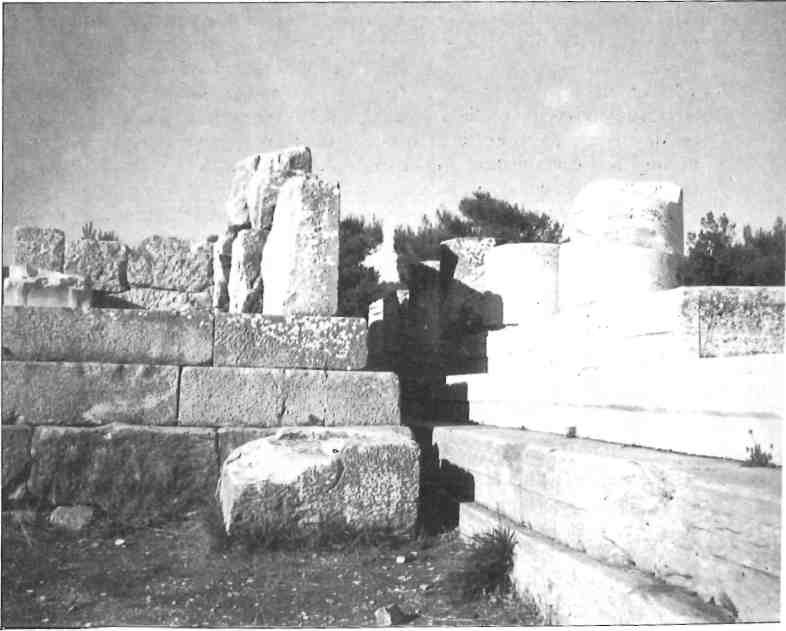

The approach to the site follows the course of the ancient road leading down into the city. The temple site itself occupies the terrace on the left. This is the Sanctuary of Nemesis, consisting of two temples facing east, side by side, with less than a metre separating them. The smaller temple to the left was built in the sixth century B.C. It was dedicated to the goddess Themis, who helped Deucalion and Pyrrha to reestablish the human race after the flood. The temple is architecturally simple, with two Doric columns supporting the front porch, and no exterior colonnade. Two marble thrones, recently returned from the National Museum, stand on the porch flanking the door. All that remains of the walls are large stones of beautifully fitted polygonal masonry.

Just to the right of Themis’ is the larger temple of Nemesis, goddess of just and inexorable punishment. Nemesis was thought to be especially harsh in retribution to those guilty of hubris, that overweening pride so offensive to the gods.

The ancient Greeks had long observed that pride goeth before a fall, and Nemesis was the personification of this oft-demonstrated principle. The fifth century B.C. provided perhaps the most dramatic fulfillment of Nemesis’ powers. Work on her temple ceased upon the outbreak of hostilities between Athens and Sparta in 432 B.C*, the beginning of the disastrous Peloponnesian War. Athens’ excesses in pursuing her imperial aspirations had roused the suspicion and finally, the fear of the Spartans and their allies. The two great city-states and their allies rent Greece, and Athens, in the course of 30 long years, fell from the height of glory. At the war’s end her empire was dismantled, her fleet destroyed and a Spartan garrison billeted on the Acropolis. This drastic change in fortune was not lost on the Greeks. After all, they’d seen Nemesis in action before on a greater scale when Greece had humbled mighty Persia. In the years following the spectacle of the Persian king’s catastrophic failure to add Greece to his empire, certain influential citizens must have felt that no expense should be spared in placating so powerful a deity, whose chastisement of the proud had so recently saved Greece.

A great architect was commissioned to raise Nemesis’ temple at Rhamnous. His name is lost but his other works appear to include the temple of Ares in the Athenian Agora, the temple of Hephaistos, or Theseion, above the Agora (whose cornice-blocks, incidentally, were discovered to be interchangeable with those of the Ares temple), and the dramatically situated temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion.

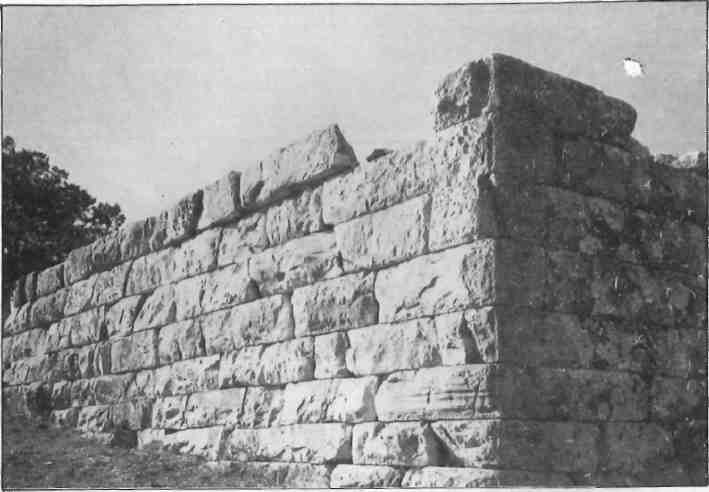

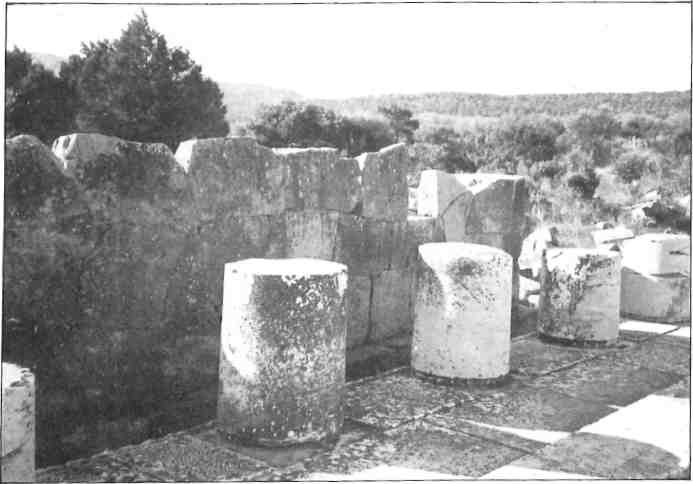

The Nemesis temple, like the others attributed to this anonymous master, is Doric, the most forceful and austere of classical architectural orders. What remains today is a fine, three-stepped stone platform. The floor, or stylobate, is of old, glossy marble delightfully marred with carved graffiti of various dates and provenance.

Of the columns, only the lowest drums are standing on the south side of the temple. The number of columns is unusual – a departure from the Doric formula of twice the number of columns on a side as on an end, plus one. Thus Doric temples usually have six columns at each end, 13 on the sides. The Parthenon has eight on the ends, 17 on the sides. The Nemesis temple, however, had six columns front and back, but only 12 on each side, demonstrating the architect’s willingness to experiment with proportion within the framework of post-and-lintel temple architecture.

To the 20th century mind, used to the rapid succession of bold and sweeping trends, such conservatism may seem staid, but it is important to remember that refinement, not revolution, was the field of play for the classical architect. He felt that his art was primarily the further perfection of the relationship of the vertical to the horizontal, of post to lintel.

A chain-link fence now separates the sanctuary from the rest of the site, which is under excavation, and not accessible to the public. It is reached by continuing on the path of the ancient road which slopes downhill towards the sea. The remains of grave monuments border the road, reminiscent, being on the approach to the city, of the Outer Kerameikos and Eridanos cemeteries in Athens, though in an inferior state of preservation or restoration. The purpose, of course, was the same – to remind both citizens and visitors of the glorious past, represented by the illustrious dead.

These cemeteries too are reminiscent of the implacability of Nemesis in her punishment of those whose arrogance leads to immoderation. On visiting the Eridanos cemetery, walking along the Street of Tombs lined with the magnificent monuments of Attica’s notables, or peering through the fence down the road into Rhamnous, one reflects naturally on the toll taken by the constant internecine bickering of ambitious states in classical antiquity. A heavy price was paid for a city’s hubris – the lives of the innocent in plague or famine; the lives of her best men in battle.

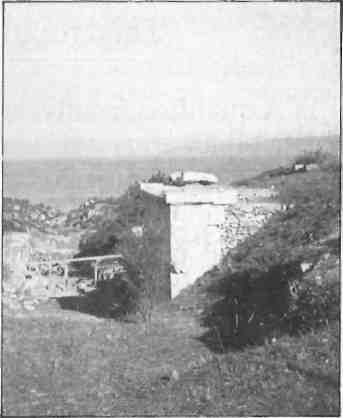

About 350 metres down the ancient road from the temple of Nemesis is the fortified acropolis, which stands by the sea on a rocky hill about 50 meters high. Elements of marble walls of Hellenistic masonry survive in its five defensive towers. The confines are on two terraces where the remains of houses of Classical and Roman periods may also be seen. The main purpose of the citadel apparently was to control the straits. The ruins have been called Ovrio Kastro, Castle of the Jews, for centuries by villagers in the district who believed that the fortress was built by wandering Jews, or gypsies.

On the right side of the road, as one descends towards the sea, may be seen vestiges of a small temple of Dionysios and a theatre that was probably the place of assembly for the citizens of the town.

Ancient Rhamnous was divided into an upper and lower town and possessed an active harbor, the source of this ancient deme’s prosperity and influence. Excavation has confirmed Rhamnous’ position in historical accounts as one of the more populous and extensive of the demes of Attica.

The earliest archaeological work done at Rhamnous was conducted by the Greek Archaeological Society between 1890 and 1894. The Society returned in 1922 for a single season. The French School of Archaeology has since excavated here extensively, especially in the area of the town itself.

The proximity of Rhamnous to Athens makes it an attractive destination for those seeking a day’s respite from the close-order drill of Athens and her suburbs. We recommend packing a picnic lunch and driving north on the coast road to Marathon. Those who have not yet paid respects to those glorious dead who at Marathon in 490 B.C. helped “turn the Mede” may wish to visit the tombs of the Athenians and Plataeans that lie on the east and west sides of the road, respectively. They are found on the site of the battlefield at Marathon, very close to the road, making their consolidation with an excursion to Rhamnous easy indeed.

Continuing past Marathon, look to the right for the turn-off to Souli. This road passes through pastureland where horses graze, and then suddenly becomes potted with some very substantial holes. Be alert for this development as it occurs unexpectedly, and ‘can be teeth-rattling. This problem persists only for a few hundred metres, after which the road is excellent, a lovely progress though irrigated fields. Presently, the road makes a 90 degree turn to the left. From here, Rhamnous is only four or five kilometres away. There is only one sign for Rhamnous itself on the left just two kilometres from the site. Look for a sandy parking area on the right and the gate to the sanctuary. Admission is free.

Nemesis: in pursuit of the inescapable

by Sloane Elliott

Among the most appealing aspects of Rhamnous are the resonance of its name, the charm of its location and the fact that it has a sanctuary dedicated to Nemesis.

Had it been Hera or Athena or even Aphrodite who was once worshiped on this hillside terrace, we would be less moved. For now those goddesses are gone, victims of man’s spiritual fickleness, but Nemesis is still right here with us – in us. She is, to her immortal good fortune, a psychological fact and that is why even the word ‘nemesis’ alone may still send a tremor through our skeptical hearts.

Right in historical times she was transformed from an object of ancient worship into a subject of modern morality. The sanctuaries of the ancient world are crowded today with the wraiths of deities no longer believed in – unless package tourists, mistaking them for guides, ask them the way to the nearest restroom. But Rhamnous is special, full of the old bewitchments and our state-of-the-art anxieties.

The cult statue of Nemesis at Rhamnous was very grand and everyone who saw it made a big thing of it. A bit of her face in the British Museum (not enough for Melina to make a fuss over) attests to its great size, and lots of fragments in the National Archaeological Museum here confirm its fine workmanship. The story of its making is interesting because it tells us why we feel about Nemesis as we do. Many cult statues gained sanctity by their origins in myth, or by the supposed acts of the very gods involved, with xoana falling, as manna does, from heaven. But the statue of Nemesis was created in the odor of dissanctity which implies that her godhead was already being ‘violated’ by morality in the early age of reason.

Pausanias and others confirm that the statue in question came into being in the following way. When Datis, Darius’ general, crossed the Aegean with his Persian army to chastise Athens for having taken part in the Ionian Revolt, he subdued Paros among other Cycladic islands along the way. There he found a great slab of marble which he took along with him for the purpose of setting up a trophy on which he meant to inscribe the details of his great victory over the Athenians. But, as every schoolchild knows, things turned out quite differently, and after the Battle of Marathon the victorious Athenians were amazed to see this tremendous slab lying abandoned on the plain. It must have been an impressive sight for if we follow the calculations of Professor George Despinis it must have stood at least half as high as one of the monoliths at Stonehenge.

When and how this stone was transported, whether by land or sea, the ten-kilometre distance from the soros of Marathon to the sanctuary at Rhamnous is unknown. Nor do we know where it was sculpted. Pausanias says the creator was Phidias himself; most agree today that it was his pupil Agor-akritos. Most scholars also agree that it was finished and in place by the beginning of the Peloponnesian War and that the elaborate pedestal along with its frieze was completed during the Peace of Nikias.

It would be a tidy thought if one imagined that this colossal statue was erected at Rhamnous simply because of its imposing site so close to one of the great military upsets in history. But in fact Nemesis had been connected with Rhamnous long before the Persian Empire came into being, probably before anyone had any conception of hubris.

Who was Nemesis? There are so many traditions surrounding her, often contradictory, that one can only be awed by the fertility of the human imagination before the ‘age of reason’.

According to the Cypria, a lost epic of the Homeric cycle, Zeus became infatuated with her on Cyprus. A strenuous pursuit followed, because she kept changing her shape, until, in the form of a swan, she reached Rhamnous where Zeus finally had, as they say, his way with her. Then, others say, she went to Sparta where she gave birth to Helen who was at once kidnapped by Leto, the Lacedemonian queen. In any case, a central section of the statue’s pedestal, according to Pausanias, showed Leto presenting her foster daughter to her real mother Nemesis.

But it is persistently repeated in myth that Helen emerged from an egg dropped from the moon, so it’s not surprising that Nemesis is said to be an aspect of the Moon goddess in Attic garb while Leto.is the same in her Spartan epiphany. Of course the Attic version would be favored here. Nemesis had other Eastern connections, too, and was worshipped as Adrasteia, the Inescapable One, up and down the Anatolian coast of the Aegean, and especially at Smyrna. There, coins were minted showing two Nemeses, but let us not get into that when the pursuit of just one is so challenging.

To have Helen the daughter of Nemesis sounds like the primitive male attempting to describe a femme-fatale, and in fact these abducted girls seem suspiciously like long-established goddesses now stolen by men to give their new-fangled patrilinear societies legitimacy.

Modern interpretations of Nemesis are almost as diverse and colorful as ancient ones. George Thomson, who tends to find Karl Marx lurking under every prehistoric stone, has made a long and convincing study of deities related to very early agricultural, communitarian societies. Though he does not mention Nemesis specifically, he speaks at length of the Moirai, the goddesses who parcel things like land and livestock out fairly. Many scholars have identified Nemesis with these: hence the early definition of nemesis as “distribution of what is due” or “allotment”. Archaeologists stress these argicultural origins of Nemesis at Rhamnous.

How Nemesis was transformed from a myth into a moral principle is itself an intriguing glimpse of man’s emergent self-consciousness. E.R. Dodds, who is attracted to Freud as Thomson is to Marx, opens another vein of thought.

In following out the evolution of man’s idea of himself in the period between the Heroic Age and the early Classical, he sees a transition from a shame culture to a guilt culture, with old beliefs not so much changing as man’s reaction to them.

In the earlier period there was a feeling of divine hostility – not that the gods were evil but that they resented any human happiness, as an infringement on their rights. May this indicate the gods on the defensive against the growing rationality of man?

Dodds sees phthonos, or divine jealousy, as a source of religious anxiety which is then moralized as nemesis, righteous indignation. But man’s success also produces koros, or complaisancy, which in turn generates hubris, or arrogance, and that is when nemesis is aroused. The arrogance once was felt to be so widespread that it was called themis, or established usage, in the Homeric Hymn to Delian Apollo. It is interesting that it is Themis, how personified, who is honored in the little temple so close to that of Nemesis at Rhamnous.

So, Nemesis, as the psychological awareness of human arrogance and the existential anxiety which it produces, has no trouble keeping intimate company with man through the ages. Today, she may be up in the atmosphere looking into ozone holes or down in Amazonia checking out those ingenious new saws that can cut down trees 50 times faster than former ones. The ancient Greeks were always admired for the suitability of the locations they chose for the temples they raised to their particular gods, and that of Nemesis at Rhamnous is no exception. It is perhaps the loveliest spot left in Attica today, and just the perfect place to ponder that Nemesis frowns on species that are too successful and endanger ecological balances, encourages caution, abhors complaisancy and demands decisions, for otherwise her vengeance, they say, is terrible.