What do you call a man who at the age of 36 has himself circumcised the more safely to visit Mecca; who learns Russian in six weeks, four languages in a year and 17 in all; who recruits the Archbishop of Athens to find him a wife; and who spends 20 years making a fortune in order to verify the historical truth of a picture his father showed him when he was seven? Genius, lunatic, visionary, charlatan: Heinrich Schliemann has been called all these and more.

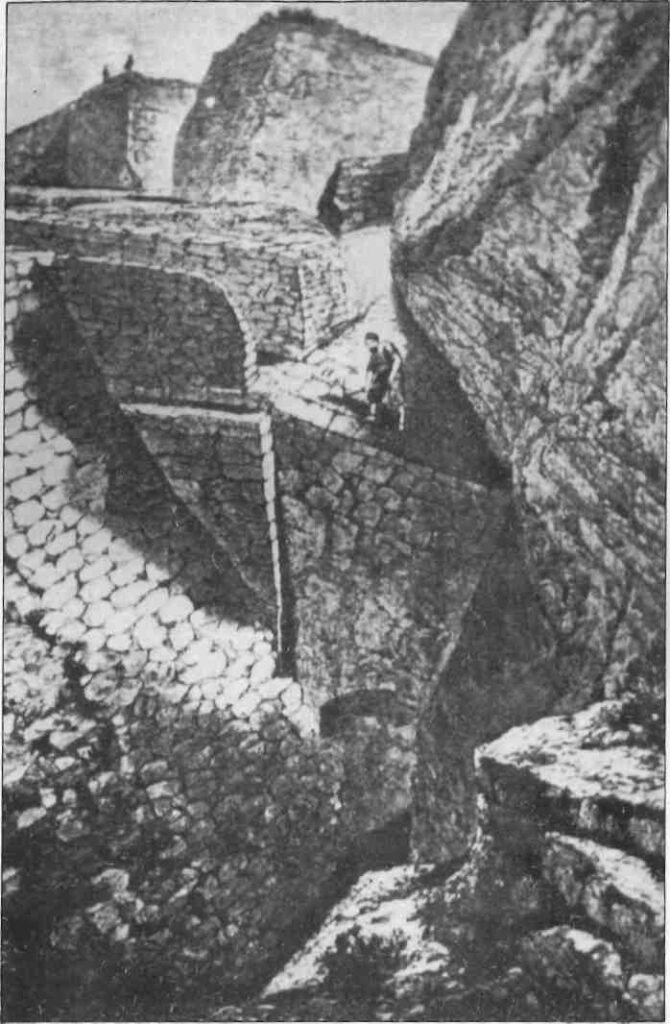

As an archaeologist, he discovered Troy and vindicated Homer, to the chagrin of armchair classicists: he demonstrated the great power and wealth of ancient Mycenae; and at Tiryns he showed that a fortress scholars dismissed as Byzantine had stood for three and a half millennia. Schliemann turned the world of archaeology on its ear – and the classicists fought back, accusing him of every sin in the demonology of scholarship, from faulty working methods to flawed logic to outright fraud. He was one of those extraordinary polymath amateurs that the second half of the nineteenth century threw up in such profusion – perhaps the greatest of them all.

Schliemann was the son of a drunk-en and dissolute pastor in a small North German town, who had an affair with the housemaid during his son’s childhood and was later suspended from his parish after having been accused -wrongly – of embezzling church funds. Books change history. The seven-year-old Heinrich saw an artist’s impression of the walls of Troy in a history book. His father said Troy had totally disappeared, but the boy reasoned that such mighty stone ramparts must still exist, even if buried by earth. He resolved to dig and find them one day. How he and Sophia, his Greek mail order bride, set out with a fierce and single-minded passion to fulfill the childish aspiration is one of the great adventure stories of science.

Leaving school at 14, Schliemann was sent to work as a grocer’s assistant. For five years he worked from five in the morning till 11 at night with no chance to study. Only a drunken customer who drank potato-spirit as he recited Homer kept the dream of proving the historical accuracy of the Iliad alive. Weak, sickly and tubercular, Schliemann decided to improve his health by taking a long sea voyage, intending to seek his fortune in Venezuela. After a nine-hour ordeal off the Dutch coast in a tiny storm-tossed ship he was thrown up on a sandbank, naked, semi-conscious and with two smashed front teeth. He was always to maintain that the immersion dramatically improved his constitution, so that thenceforth he bathed daily in the sea, summer and winter.

After a spell in an Amsterdam hospital, Schliemann took a job as a book keeper. He learned English by attending the English church twice on Sundays and repeating the words of the vicar under his breath: His memory was phenomenal. In time, he could recite 20 pages of English prose word-for-word after reading them through three times. He committed the whole of Scott’s Ivanhoe to memory. Many years later, on a train journey, he startled his daughter, who was reading that novel, by reeling off page after page of it. In his twenty-first year, Schliemann learned four languages. Taking a job as a bookkeeper with the firm of Β. Η. Schroeder, he learned Russian in six weeks (in order to communicate with Schroeder’s Russian customers) with no teacher but a grammar, a dictionary and a translation of Fenelon’s Telemaque. Sent to St. Petersburg as an agent, Schliemann was given permission to trade on his own account. He quickly amassed a fortune and acquired a Russian bride, a beautiful but passive creature, wholly unsympathetic to his ardent enthusiasm. He had sought out Minna, his childhood sweetheart, as soon as he was financially independent, only to learn that she had just married. Extravagant in every emotion, Schliemann was prostrate with grief and took to his bed for several weeks.

In 1851, Schliemann was in California, searching for the grave of his younger brother who had made a fortune in the Gold Rush but hadn’t lived to enjoy it. Schliemann’s visit was eventful. He nearly died of yellow fever, opened a bank, (almost in passing amassing another fortune of $350,000) and, awakening one night to find the building next to his hotel on fire, he climbed to the safety of Telegraph Hill to watch the fire consume San Francisco. Back in Russia in 1852, he traded arms during the Crimean War, later seeking to justify himself by pointing to the noble goal for which he was accumulating his wealth.

While building his fortune during the following 15 years, Schliemann still managed to travel widely in Europe and Asia, but his most remarkable journey was to Mecca. A man with the restless curiosity of the polymath, he had long wanted to witness the Moslem ceremony of purification at Islam’s holiest site. The word “impossible” wasn’t in his vocabulary, in any language.

Schliemann travelled to Arabia, committed the Koran to memory, had himself circumcised, bathed three times a day in the sea in order to heal the wound and sunbathed naked to darken his body. He then made his way to Mecca, clad in the white robe of the penitent and entered Mohammed’s holy mosque. Reaching the Kaaba, the holy of holies, he received the supreme blessing, prayed and chanted his allegiance to Islam and was anointed with holy water from the Zamzam Well. Schliemann for many years kept this sacrilegious act secret for fear of fanatics seeking retribution.

While in the US, Schliemann had divorced his Russian wife. He wrote to his friend and former tutor, Vimbos, now an Archbishop, asking him to choose a suitable wife, of pure Greek stock, intelligent but unsophisticated and as lovely as Helen of Troy. From the photographs of Vimbos’ poor female relations, Schliemann chose Sophia Engastromenos. He was 47; she 17. Hearing her recite from the Iliad in school moved him to tears and confirmed his provisional view. After a far-from-calm courtship, made no easier by his being besieged by Athenians urging upon him the merits of their respective daughters, the two were married. Schliemann, seeing himself as Professor Higgins to her Eliza Dolittle, encountered instead a will as strong as his own, a wife resentful of his remorseless attempts to educate her. But mutual respect and esteem grew into love, and they conquered the world of archaeology walking side-by-side as equal partners.

From 1866 to 1871, Schliemann studied in Paris and turned himself into an archaeologist. He visited Troy in 1868 and dug on Ithaca, his book Ithaca, The Peloponnese and Troy earning him a doctorate from the University of Rostock. It was to Paris that he brought his young bride in 1869 and that year and the next were spent fretting over the failure of the Turkish government to grant a firman permitting Schliemann to dig for Troy on the hill of Hissarlik in Asia Minor. Arriving in Greece in February of 1870, he toured some of the Cycladic islands, but, bored and irritated, resolved on 5 April to set off for Hissarlik the following day, without permission or preparation. Sophia, ordered to pack at once, refused point-blank to accompany him. Next day he sailed for Constantinople alone.

After careful study of Homer’s text, Schliemann was sure in his own mind that Troy was at Hissarlik, not at Bunarbashi, the site favored by most of the scholars who did not consider the Iliad to be folk-mythology. He dug his first trench with two helpers. The next day he signed up another 19. But realiz-ing, after his first quixotic impulse, that he could achieve nothing without proper preparation, he was back in Greece by 22 April.

In January 1871, infuriated by bureaucratic chicanery over his firman, Schliemann returned to Paris, then under Prussian siege. Sneaking through enemy lines at night, he witnessed at firsthand the awful privations of the wartorn capital. The Schliemanns set put for Constantinople in September 1871 and this time got their firman though with the stipulation that everything found would belong to the Turkish government.

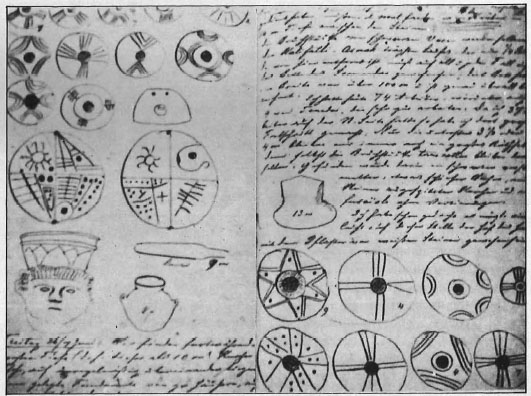

Digging then started in earnest. In the next two years, seven separate Troys were unearthed. But Schliemann’s methods were sometimes erratic and unscholarly, he published overconfident claims prematurely and he reeled beneath a violent academic barrage. He meant 1873 to be his last season at Troy.

One morning in June, on the penultimate day of the dig, Schliemann, working with Sophia, spotted something – a large copper artifact with another object gleaming near it. The workmen were told that it was the archaeologist’s birthday and given the day off. While Schliemann dug out gold, silver and copper artifacts, heedless of the fortification wall louring over him and threatening to collapse at any moment, Sophia smuggled the precious cargo back to the house in a large red shawl. Afterwards, they locked themselves in for a good gloat. They had painstakingly dug out more than 10,000 objects that morning: one diadem alone consisted of 16,353 separate pieces of gold. Somehow they smuggled the finds back to Athens under the nose of the Ottoman overseer; how, we shall never know, since they never told anyone or recorded how it was done.

To Sophia’s great mortification, Schliemann eventually presented the collection to the German nation. Most of it disappeared during the Battle of Berlin at the end of World War II.

Schliemann’s Midas touch was again demonstrated at Mycenae where he began to dig in 1874. Alone among scholars, he interpreted Pausanias as saying that the royal graves of Mycenae were inside the Cyclopean Walls. The main dig began in 1876 and attracted many distinguished visitors: the Emperor of Brazil was feasted in the Treasury of Atreus. In November, Schliemann struck gold again and proved his point about the royal tombs. To the right of the Lion Gate inside the walls, a royal grave circle was excavated with five shaft graves. Among the treasures found was the famous gold mask that Schliemann initially believed had covered the face of Agamemnon -well-preserved in the grave, eyes and mouth intact with 32 teeth, although the nose and hair were gone.

On his honeymoon, Schliemann had promised to build a palace for Sophia in Athens. Just ten years later, the great house on Panepistimiou St was completed. A ball was held to show off the mansion to the fashionable of Athens, including several cabinet ministers, but the next day there arrived a demand from the Council of Ministers that Schliemann either cover or remove the nude statues on the roof so as not to affront public decency. Schliemann was angry, Sophia amused. Together they plotted the discomfiture of the puritans. Servants were sent to recruit seamstresses, who worked late into the night. The following morning the statues were covered – in ballerinas’ tutus fashioned of the most hideous materials in violently clashing colors.

Schliemann passed among the laughing throngs that jammed the street explaining, in confidence, that he had been acting on orders from the Council of Ministers. A Council meeting was held that same morning, and Schliemann was requested to remove the offending garments. This he did in person, gleefully waving each dress in triumph above the crowd below.

Schliemann possessed every virtue except consistency and moderation (if they be virtues.) He himself wrote: “It is the unfortunate fate of our family to be of fiery nature and to feel very deeply:.. Intense desire, hopeless passion, can drive us to despair and madness.”

His biographer, Ludwig, notes, “the imaginative impulse in an inveterate realist; the calculating shrewdness in the visionary.”

The man who sent his shirts to London from Greece by ship to be laundered would quibble with a tradesman over ten drachmas. Perhaps the rich have to do that to stay rich: they are the natural prey of the rest of us.

Schliemann possessed an unquenchable vitality and intensity, a restlessly energetic, egotistical temperament, perpetually kindling to new enthusiasms. It is impossible to imagine him bored, pottering about the house in carpet slippers. “Troubles and excitements I have in plenty,” he once wrote, “but troubles and excitements I must have if I am to live.”

Dramatically he lived; dramatically he died. He was in Naples. He had gone just before Christmas to look at the antiquities. A severe ear complaint flared up and he called in a doctor, who, unfortunately was an amateur archaeologist. Together they made a foolhardy trip in foul weather to Pompeii to inspect the newest digs.

The next day he awoke in agony, set off to walk to the doctor’s and collapsed in the street. An ambulance was called which took him to a hospital from which he was turned away, having neither money nor papers on him. Finally, the police discovered his doctor’s address on a scrap of paper in his pocket. He was returned to his hotel suite, where the next day, while eight famous Italian doctors were debating whether to operate, he took things – as ever – into his own hands by dying.