At some point during the mid second century A.D., Aulus Gellius travelled from Rome to Athens “in quest of culture”. He was proud to be a guest of that eloquent Greek, Herod Atticus, who besides being one of the foremost sophists of his day, was also one of the wealthiest men in the Roman empire. Herod Atticus commonly received his guests and students at his villa in Kifissia, and in his book Attic Nights, Aulus Gellius records how they sat around the table talking after dinner, enjoying the respite from the heat of summer.· He describes the grounds of the villa, “the shade of its spacious groves, its long soft promenades, the cool location of its elegant baths with their abundance of sparkling water, and the charm of the villa as a whole, which was everywhere melodious with plashing waters and tuneful birds.”

The portrait bust of Herod Atticus in the National Archaeological Museum shows a slim man with fine features and a melancholy expression. It was found in 1961 in Kifissia near the little church of Panaghia Xydas on Tatoiou Street. Archaeologists also found a bust of Polydeukios (one of Herod’s students) and part of an arm made of black marble, possibly coming from a statue of Memnon, Herod’s Ethiopian admirer. The above, plus a horse’s head and some remains of buildings were all found on Rangavis Street, to the north of the church of Panaghia Xydas and a bit to the west of where the street crosses Strofyliou.

The antiquities enclosed behind glass in a funny little wooden building with a tiled roof on Platanos Square, practically in the center of the biggest Kifissia traffic-jam, are only about 650 metres southeast of the site mentioned above. They comprised a square tomb containing four sarcophagi, one of which was larger than the others and decorated with carvings. The tomb was built of large square blocks of Pentelic marble and is very similar to a tomb in Halandri, today part of the old church of Panaghia Marmariotissa. It is very likely that both these tombs were commissioned by Herod Atticus for members of his family or his close friends.

Herod Atticus (101/2-177/8 A.D.) was born in Marathon of an aristocratic Greek family claiming descent from the Aeacids. These were landowners and possibly involved in lending money as well. Herod Atticus’ grandfather, Hipparchus, fell out of favor with the emperor, Domitian, and first lost his land; then his life. Hipparchus may have been able to conceal some of his wealth from the Romans, because his son, Atticus, restored the family fortunes with suspicious ease. Keeping a low profile until emperors and times changed, Atticus discovered a treasure in one of his houses in Athens near the theatre of Dionysos. The current emperor was Nerva who was more favorably disposed towards Greece. Atticus, nonetheless, wrote cautiously to the emperor without giving too many details, saying, according to Philostratos, “O emperor, I have found a treasure in my house. What do you bid me to do about it?”

“Use what you have found,” replied Nerva. Whereupon Atticus wrote to him explaining that there was rather a lot of treasure, and the emperor answered, “Then misuse it, for it is yours.”

Thus, once more a wealthy man. Atticus gave his son Herod the best education that money could buy and launched him in the highest circles of the empire. When Herod overspent state funds as Administrator of the Free Cities of Asia while building an aqueduct for Alexandria Troia, and his enemies complained to the emperor Hadrian, Atticus wrote an arrogant letter to the latter, saying; “Do not, Ο emperor, allow yourself to be irritated on account of so trifling a sum. For the amount spent in excess… I hereby present to my son, and my son will present it to the town.”

Yet when Atticus died, he left his fortune tied up in a curious way, almost as though he meant to disinherit his son. He promised to pay each Athenian so much per year in perpetuity. Herod, however, offered the Athenians a lump sum in settlement, and they accepted. One can imagine their fury when they went to collect the money and found that Herod had charged them for debts owed to his family by their parents and grandparents. Not only did they get less than they had expected, but some got nothing at all. Others were even held up for debt in the market place.

The Athenians never forgave him for this trick, and when he built the Panathenaic stadium they said it was well named, since it was built with money belonging to all the Athenians.

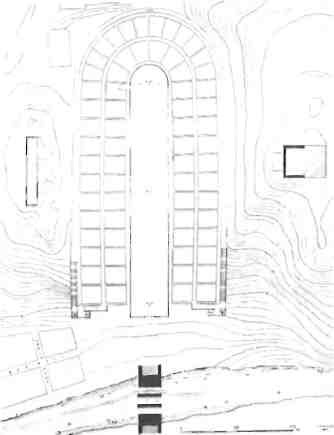

Herod Atticus studied and taught rhetoric and philosophy. He built great public monuments not only in Athens, but also in Olympia and Corinth. The stadium in Athens was built for the Panathenaic games of 143-144 A.D., and was entirely covered in white marble, amazing Pausanias who saw it soon after completion and who commented that Herod had used a whole year’s production of Pentelic marble to build it. It seems that Herod owned the marble quarries on Mount Penteli. He also appears to have been motivated by an urge to outdo the emperor Hadrian who was lavishing monumental buildings on Athens at the time.

Herod built his villa in Kifissia, or at least remodelled it, around 143 or 144, for his young bride, Rigilla. She was the daughter of Roman aristocrats and related to the emperor who succeeded Hadrian, Antoninus Pius. This was the couple’s favorite residence and where they received all the visiting notables of their day. When Rigilla died (160/1), Philostratos described Herod as feeling such despair that he altered the appearance of his house, using black hangings and dyes and Lesbian marble (“which is a gloomy and dark marble”) to make the paintings and decorations of the rooms black. Could this have taken place in the Kifissia house? In any case, Herod was soon reproached by one of his friends for losing his self-control and forgetting the golden mean. When Herod refused to listen, the friend went away in anger, and commented to slaves washing radishes for Herod’s dinner: “Herod insults Rigilla by eating white radishes in a black house.”

The threat of ridicule influenced Herod where good advice had not, and he removed the signs of mourning from his residence. But he built in his wife’s memory the Odeion that we know today as the theatre of Herod Atticus. Pausanias, who wrote about it in 173 and Philostratos, who described Herod Atticus in his Lives of the Sophists, found it especially magnificent and both mention the incredible roof of cedar that covered it. It was one of Herod’s last major projects and perhaps the most important and impressive.

Herod Atticus was always desperate in his grief – flinging himself to the ground and beating the earth when his daughter Elpiniki died – until once more rebuked for excessive behavior. It was either her death, or the death of another child, that made him so reckless with the Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Sirmium. The Athenians, still unforgiving and perhaps jealous and irritated by his arrogance, had accused Herod of tyranny (as after Rigilla’s death they had accused him of murdering her, an accusation that appears to have been completely unfounded). When called before the emperor’s tribunal, instead of giving his defense he spoke aggressively: when the pretorian prefect threatened him, he retorted, “My good man, an old man fears few things!”

He was disappointed in his son, Braduas, who was a spendthrift, an alcoholic, and, it seems, unable to learn the alphabet. Herod ordered that 24 boys be brought up with him, each one’s name starting with a different letter of the alphabet, so that his son would have to learn the letters while learning their names. When he died, Herod disinherited his son, leaving his money to other adopted heirs. His favorite students and foster sons also died young. He was particularly attached to Polydeuces and Memnon, and he put up statues of them everywhere. When he was censured for extravagance in this matter, he said, “What business is it of yours if I amuse myself with my poor marbles?”

His favorite place of residence, other than Kifissia, was Marathon, his home town, where he was born and where he died. Philostratos describes him as coming up to Athens to meet a visiting philosopher, wearing an Arcadian hat as was the fashion during the summer then. Did he come straight up from Rapentosa, past the sanctuary of Dionysos (whose ruins one can visit today within a humble wire enclosure on one’s way via Dionysos to Nea Makri) or did he take a more roundabout route up the head of the Avlona valley to Stamata?

Herod Atticus had various properties in Marathon. One of his busts, which can be seen in the Marathon museum, was found near the Tomb of the Athenians. Impressed by Egypt after a visit there, he even built an Egyptian temple at Marathon and this must explain the Egyptian statue in the museum there. Another of his properties was located up the Avlona valley, not very far from the Tomb of the Plataeans.

This isolated property was encircled by a stone wall, 500 metres in circumference, made of unworked stone without any cement. A gate (built of well-cut limestone blocks) marked the entrance to the property. It was about two-and-a-half metres high, three-and-a-half wide and surmounted by an arch with an inscribed cap stone.

The inscription announced the Gate of Immortal Concord, stating: “The space you are entering belongs to Herod”. On the other side it repeated, “Gate of Immortal Concord”, and dedicated the space to Rigilla. There were also two seated figures, today headless, one male and one female, perhaps representing Herod and his bride. One can still see a small section of the wall today on the right side of the Avlona valley, but it is now inside a military area.

The ruins of the gate, moreover, have been removed lock, stock and barrel by archaeologists and no trace whatsoever remains of the site they once occupied, somewhere to the left of the new road leading to the military compound. The stones themselves may be found lying in a melancholy row along the wall of a building on the grounds of the Marathon museum. One can just make out the inscription.

Old guide books often refer to this property as the Mandra tis Grias – a sheepfold or goat-pen belonging to an old lady. It’s amusing to find she and her giant goat-pen linger on in the name given to the area on the Greek Army Geographical Service map of Penteli, where the head of the Avlona valley is marked Gria. A farmer in the area told us that his grandfather remembered thousands of goats penned in the valley, belonging to an old lady.

This mysterious property may have been a park for hunting, or an untamed reserved for meditation. If one stands somewhere in this area and, looking up at the foothills of Penteli over which lie Kifissia and Athens, it is not hard to imagine Herod Atticus in his shady Arcadian hat sitting there – a man whose wealth did not ensure his happiness, who learned easily, but worked hard, studying even while he drank wine, or at night when he couldn’t sleep; a man who, embittered by the behavior of the Athenians, lived in self-imposed semi-exile at Marathon and Kifissia; a man who considered himself a failure because he couldn’t drive a canal through the isthmus at Corinth.

He died of consumption at Marathon in 177 or 178 and though he had asked to be buried there, the Athenians raised a tomb for him in Athens, near the Panathenaic Stadium on Mount Ardettus, and according to Philostratos, inscribed over him the following epitaph: Here lies all that remains of Herod, son of Atticus, of Marathon, but his glory is worldwide