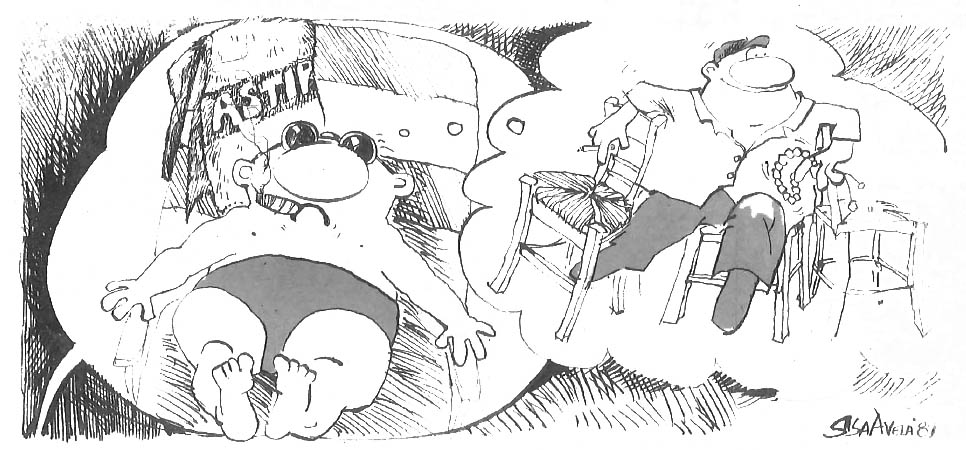

“Now tell me what makes you think you’re on the verge of a nervous breakdown.”

The man sighed, mopped his brow with the handkerchief he had screwed up into a ball in his left hand and made a helpless gesture with his right.

“It was the swimming pool,” he said, ” there were a lot of other things too, but it was the swimming pool that pushed me to the edge. It wasn’t the cost, mind you, although that was pretty steep. It was the constant hassling with the contractor, the workmen, the plumber, the electrician and everybody else involved. I was against it from the start because I knew what we would be letting ourselves in for, but my wife was adamant.”

“As soon as she heard they were putting a swimming pool on the grounds of the Villa Galini, she handed . me a piece of paper with a name and a telephone number scribbled on it and said to me: ‘Bibiko, (that’s her pet name for me), this is the name and phone number of the pissinas who’s building the prime minister’s swimming pool. Get in touch with him and get him to build one for us, too. Twelve metres by six will do us nicely and I know just the spot in the garden where it can go’.”

“I said to her, ‘For one thing, a man who builds swimming pools is not called a pissinas and for another, after all we’ve been through with contractors, carpenters, plumbers, electricians, painters, landscape gardeners and the rest of them so we can live in relative comfort in this little six-bedroom villa of ours in Politeia, don’t you think we need to recuperate for a couple of years at least before going through the whole rigmarole again for a swimming pool?'”

“She said a simple ‘no’, and added, ‘We’ve eaten the donkey, we might as well eat the tail’.”

“So we went ahead with the swimming pool and every time there was a hitch – and there were a million of them – she would call me wherever I happened to be and ask me to handle it.

She would even call me when I was attending a cabinet meeting. She would tell the secretary it was a matter of life and death and then she would say to me, ‘Bibiko darling, be a peach and ask the prime minister if he’s putting a diving board at the deep end of his pool.’ Can you believe it? Isn’t that enough to push anybody to the edge?”

The psychiatrist nodded. “You said there were other things besides the pool, what were they?” he asked.

“I haven’t finished with the pool yet,” the man said.

“You remember the heat wave we had this summer? Well, after all the hassles had been resolved, the pool was finally ready and we were all thankful we would have something to cool off in during the heat. We inaugurated the pool with a party that was written up by all the society columnists in the magazines with color pictures – they called it the ‘highlight of the season”

“I remember,” the psychiatrist broke in, adding pointedly: “I wasn’t invited.”

“I know,” the man said, “it’s a pity we forgot you. You would have found many eager clients among our friends but I’ll be sending them to you anyway, so no harm done. To get back to the pool, on the day after the party, the heat was really unbearable and as soon as I got home from the office, I changed into my bathing trunks and made a beeline for the water. Just before I dived in , my eye caught some suspicious looking objects floating on the surface with bits of tissue paper all around. My wife was lying on the grass by the pool throwing a fit and I realized something was very seriously wrong.”

“To cut a long story short , the underground pipe feeding fresh water to the pool had broken and so had the sewer pipe above it so that the water going to the pool was carrying with it the unmentionables I just mentioned.

It took another two months to get that fixed and now I’m in litigation with five separate individuals trying to recover some of the small fortune that the entire pool project has cost me so far.”

The psychiatrist was becoming bored with the whole story and was thinking to himself: ‘If you can afford a pool, you should be able to cope with the hassles that go with it.’ Then aloud: “Can we go on to the other things that are bugging you?”

“Oh, all right. There’s nothing specific mind. you, but it all piles up. Like the quarrel I have with the family every year when it’s time to take our summer vacation. I want to go to my home village in Ano Kathikia and stay in my parents’ home and breathe the pure mountain air, but my wife and children won’t hear of it. It’s either the Astir Palace, Vouliagmeni or the Astir Palace at Elounda in Crete or the Astir Palace in Corfu where we mingle with shipowners and the people I see every day in Athens; either I get bored stiff or I hear rumors about various changes in the administration that might be affecting my future and I break out in cold sweats.”

“Then it’s the car. My wife won’t use the car and driver my position in the government entitles me to. She says the chauffeur is a garrulous, bolshie type who lectures her on socialist theory and doesn’t use deodorant, and she wouldn’t be satisfied with one of those small, nippy Autobianchis or whatever. No, it had to be a two-litre BMW with a metallic finish and automatic transmission, and every time it goes in for servicing it costs half my month’s salary.”

“Then it’s problems with our domestic staff. After all the trouble I go to, using my influence with friends in the immigration department to have their work permits renewed, my Egyptian and the two Filipino maids do nothing but quarrel among themselves and my wife is sure one or all of them are robbing us blind, although she can’t prove it.”

“Then it’s my daughter, who refuses to have piano and ballet lessons, as well as private lessons in French, English and German, that don’t leave her a moment to herself, and has threatened suicide if we insist. But my wife is adamant about the piano lessons and I suspect it’s because the piano teacher is one of those handsome, arty types that she falls for so easily, like the damned decorator who made us buy all those nightmarish paintings hanging in our living room.”

The psychiatrist looked at his watch and broke in at this point to ask: “How do you think all of these problems of yours could be resolved?”

“I don’t know, that’s why I came to you. What I really long for is to be the way I was before 1981, with a good little job, a comfortable little apartment in Kato Patissia, children who want to the state school and had plenty of spare time, a wife who ran a tight household and shopped at the laiki every Friday, and vacations every summer at Ano Kathikia. But I guess that’s all in the past. I’ll never be able to go back to that.”

“Don’t be so sure,” the psychiatrist said, “just hold on until the next general election and maybe your dream will come true.”