Deafening amplifiers, however, were already regulation then. So, in winter, out of a kentro set at the foot of a dusty hill halfway down Syngrou Avenue, the bouzouki of Tsitsanis himself could be heard from the Phaleron delta to the Temple of Olympian Zeus; in summer, from Tzitzifies, across the water to the yacht club in Castella.

A song of Tsitsanis was in fact as much the sound of Greece as the cicada’s, and as natural and simple. A new song – he is said to have written a thousand of them – once heard, sounded as if one had heard it all of one’s life. Later in the ’50s with the emergence of Hadzidakis, of Theodorakis in the ’60s, of Savvopoulos and others in the 70s – and his influence on all of them was enormous – Tsitsanis shared his popularity in this great period of popular song. Yet it can be said with some certainty that his music spoke most intimately to the ordinary man and woman of modern Greece.

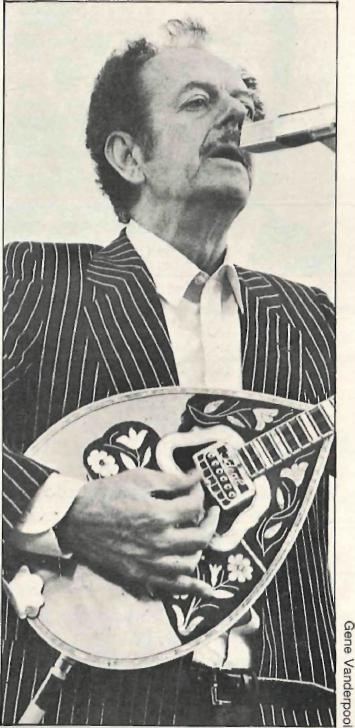

Tsitsanis was born in Trikala, Thessaly, in 1912, the son of a shoemaker (of tsarouchia, to be exact) who loved to play the mandolin. As a young man Tsitsanis studied violin with an Italian maestro. But when he came to Athens to study law at the university, he slipped into the world of rembetika with its Byzantine and Anatolian roots, its Levantine seaport atmosphere, and above all, he took up the classical instrument of rembetika’s expression, the bouzouki, without which it is impossible to imagine him.

Besides his hugely successful career as a composer, he performed with almost every famous singer of the last forty years, launching many of them on their own careers. Marika Ninou in the ’50s, Bithikotsis and Marinella, more recently Sotiria Bellou at the kentro next to the firing range in Kessariani, are but the first names that come to mind. Tsitsanis appeared at kentra so regularly and for so long that it has been estimated he spent, over the course of 44 years, a total of 12,000 nights on the performing platform, evenings that went on often till dawn. Never upstaging anyone, he played with rapt attention, pausing only for a cigarette from an ashtray or a drink from a glass which usually stood on the floor beside him. His own voice was soft and unassuming, as if he were singing to himself.

Vassilis Tsitsanis died at Brompton Hospital, London, on January 18, of a heart attack following lung surgery. An unfinished song lay on his hospital bed. It was his 72nd birthday. There was some confusion in the press at first about his age. It seems natural enough, since he never looked any age in particular and always looked the same.

At his funeral, which took place at the First Cemetery in Athens on January 21, a group of bouzouki players, joined by Sotiria Bellou, sang his songs, and others joined in with the best-beloved of all – the song which a famous artist once said was the one he most wanted to paint, Synnefiasmeni Kyriaki (Cloudy Sunday). The seemingly irregular tribute was in fact appropriate as a send-off to this great popular musician of the common man.