I have nothing against Greek-Americans in general, but I find their conversation tends to run to a pattern that can become very tedious – particularly when they have a captive audience like the one I presented at that moment.

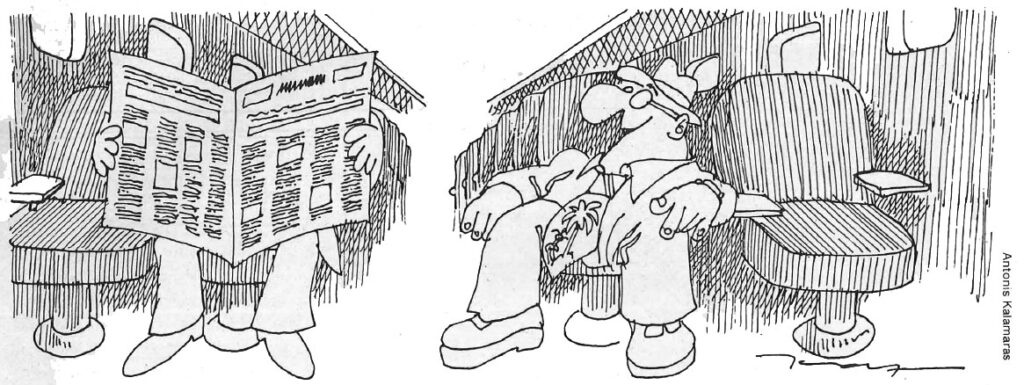

I tried to bury myself in my newspaper, but it was no use. He stretched out a gnarled and calloused hand that I imagined must have washed a Mount Everest of dishes in his lifetime, and introduced himself.

“Yannis Peripatitis, from Sparta and San Francisco,” he said. I sighed inwardly, tendered my own hand and gave him my name. He looked at me suspiciously when he heard it.

“You Rooshian?” he asked.

“No, I am not Rooshian,” I said. “I am a Greek, like you.”

He seemed relieved. Then he shook his head. “Those Rooshians are all reds, you know. Communists! You like communists?”

I shook my head in denial.

“Glad to hear it. I don’t like them either. Nothing like democracy, you know. We got a fine democracy in the United States. Nobody bothers you. You pay your taxes and nobody bothers you. You wanna open a restaurant? You go ahead and open it. You work hard, you don’t break no rules by the fire department or the sanitation department and you got toothpicks and Roll-o Mints by the cash register and everything’s fine. You make money, you buy a house and then mebbe a Cadillac and you don’t owe nobody nuttin’ and go to church on Sundays an’ everybody says: ‘Yanni? He’s a good citizen.’ That’s American democracy. Finest in the world.”

“We have democracy here too, you know,” I remarked.

He looked dubious. “Waal, sometimes you got it and sometimes you ain’t got it. In America, we got it all the time. You know what I mean?”

I nodded. I knew only too well what he meant.

“When Pangalos took over in 1922, my uncle in America wrote to my father and said: ‘Epaminondas, send the boy Yanni to me. He got no future in Greece and you got eight other kids to feed anyway. Send him to me. I got a good job for him in my restaurant.’ So I go to my uncle and I’m only a kid of twelve but I wash dishes in that restaurant for twenty years. I save up my money, I move to San Francisco, I get a loan from the bank and just before Pearl Harbor I open up my own restaurant. After the war, I write to my folks in Sparta and say I wanna get married. They send me a nice girl. She don’t look nothing like her picture and she’s kind of skinny at first but I soon fatten her up and she make a good wife for me. Three kids. One’s a doctor now, in the Mayo Clinic. You know the Mayo Clinic? Finest in the world. He’s a proctologist. You know what a proctologist is? Well, you gotta make a living somehow: The girl, she married an astronaut. Sitting in front of the TV biting her nails and eatin’ her heart out every time they shot him up there, way above the clouds. But he came back and they don’t shoot ’em up no more now like they used to. Mebbe they fire him soon, who knows? But I got a good job for him in the restaurant if they do. So that’s all right. The youngest, Costaki, he’s a chemist at a wine factory in the Napa Valley. He been to Greece several times and he loves it. One day he says to me: ‘Dad, you got some money saved up, why don’t we open a wine factory in Greece?’

‘You crazy?’ I say, ‘nobody drinks wine in Greece no more. You seen ’em at the Hilton bar? Nothing but Scotch. You seen ’em at cocktail parties? Nothing but Scotch. You seen ’em in their homes? Nothing but Scotch.’

‘Okay then,’ Costaki says, ‘let’s open a whiskey factory!’

“I still think it’s crazy but Mama kinda liked the idea of movin’ to Greece. You see, we got friends an’ all in San Francisco, but we ain’t exactly high society, y’ know what I mean? In Sparta, her folks and my folks make a big. thing of it when we visit them an’ she feels like a queen.

Then ‘I tell Costaki: ‘How ya gonna make Scotch in Greece when it’s the water from yon bonnie banks and braes or whatever that makes Scotch · taste like Scotch? An’ he says: ‘Dad, I’m a chemist. I’ll analyse the water and I’ll bring Greek water as close to it as dammit. The Japanese make Scotch, so why shouldn’t we?’

“So we get a gang of consultants to make a fizzibility study an’ we come here and we discover there’s a Law 1116 that gives ya all kinds of incentives and whatever and we go to the bank and we go to the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Coordination and then back to the bank and then to the Ministry of Industry and we get a whole pile of papers and we stick hartosima on them till our saliva runs dry, an’ we get signatures an’ counter-signatures until all the papers look like my menus back home with all the customers’ doodles on ’em an’ now here I am on my way to Larissa to find out who’s gonna supply us with the barley to get started.”

“Fascinating!” was all I could say to my flight companion’s expose of his projected investment. Then I said: “You’ll probably have to launch a massive publicity campaign to sell your whiskey. People don’t switch brands easily, you know, even if your whiskey is cheaper than others. What are you going to call it, anyway? Have you thought of a name?”

“Name? I’ll give it my own name. No problem there, my friend,” he said confidently.

I looked dubious. “Yannis Peripatitis whiskey will be a bit of a tongue-twister, won’t it? I asked.

“Oh, that’s my Greek name. The immigration officer at Ellis Island said the same thing when I landed in 1922. So he asked me what my name meant in Greek and I told him. So he gave me my American name. Here, see for yourself,” he replied, fishing out his American passport and showing it to me.

I read: “John E. Walker” and I clicked immediately.