Such was the case quite recently of Antzouletta, the pretty sixteenyear-old daughter of a brusque and impetuous tanker tycoon named Gerasimos Capulatos, and of Romaleos Montagoulis, the robust and handsome heir to the Montagoulis oil refinery and petrochemicals complex.

The two families had become sworn enemies after a shipment of oil from the Montagoulis refinery, carried in a Capulatos tanker, disappeared mysteriously in mid-Atlantic together with the tanker.

There were ugly rumors that Capulatos had sold the oil to a third party and scuttled the tanker, thus collecting the value of an oil cargo that did not belong to him and the insurance on his ship. Montagoulis, meanwhile, was tied up in knots with his own underwriters who were not convinced the oil had gone down with the tanker.

In this tense atmosphere of hatred and mistrust between the two families, young Romaleos Montagoulis first set eyes on the fair Antzouletta at a garden party in the grounds of the Capulatos’s sumptuous villa in Politeia.

Romaleos had naturally not been invited to this party but had lost his way while heading for another party in the same area. He stopped his Ferrari outside the brightly-lit Capulatos demesne and walked through the chattering throng in the garden, looking for a phone.

He saw Antzouletta standing by the open French windows of the ground-floor living room, radiantly beautiful in pink organza and a Dino & Gino coiffure and said: “May I use your phone?”

“Why, of course,” the girl said, smitten by the young stranger’s good looks and the Ferrari parked outside.

“In here.”

They went into the living room and while Romaleos was on the phone, asking for directions, Antzouletta picked up two dry martinis from the tray of a wandering waiter.

When Romaleos put down the receiver, she offered him one, saying: “How about one for the road?”

Romaleos accepted it graciously, sat down on a couch and very soon he and the girl became thoroughly engrossed in each other.

At one point in the conversation, they introduced themselves and when they realized they belonged to the opposite shores of a maritime feud, Antzouletta said:

“Damn! If my father sees you here, he’ll kill you!”

“And if my father knew I was here, he’d kill me too!” Romaleos replied.

“How are we ever to get married?” Antzouletta blushed.

“This is so sudden! But really sudden. Why, we’ve hardly known each other for more than an hour,” she cried.

“I don’t care,” Romaleos replied.

“I could tell at once we were made for each other. But how the hell are we going to work it out?”

“We could elope,” Antzouletta suggested. Romaleos shook his head.

“If we did, your father would cut you off without a penny and my father would do the same to me.

And then how would we live in the manner to which we were born?”

Antzouletta nodded. She was glad he was sensible as well as handsome.

After more discussion, they decided to put off their wedding plans until either the tanker tangle had become untangled or until time had healed the wounds between the two families.

In the meantime, they arranged to see each other secretly and they managed to do this quite successfully for the next two months.

One morning, however, Gerasimos Capulatos, in his usual brusque and impetuous manner, amiounced to his daughter that he had arranged for her to marry Paris Spirakis, the pimply son of a bulk carrier tycoon.

Spirakis pere had once taken the rap for Capulatos for stealing a bargeful of UNRRA potatoes when they were both starting their careers as lightermen in the port of Piraeus in the late forties. Capulatos considered the time had come to repay his debt by bestowing his daughter’s hand in marriage to Spirakis fits. The fact that their combined fleets would form a powerful unit in the tramp market was also far from incidental.

Capulatos concluded his delivery of the bombshell by saying: “We are having a party tomorrow at which I shall announce the engagement.” Then he stalked out of the house, got into his Mercedes 450 and drove to his office in Piraeus.

Poor Antzouletta was stunned.

This was something she had not bargained for. Aside from the fact that she was allergic to the skin-cleansing lotions Paris liberally applied to his acne-scarred face, she could not even bear to think of a pending liaison with that staphylococcic creep.

She would have to do something drastic and she immediately put to work the devious mind she had inherited from her father.

A plan came to her in the early afternoon. She decided she would fake a suicide and have Romaleos rescue her. Her father, she reckoned, would be so grateful to him, he could never object to having him as a son-in-law. And if old Montagoulis was still obstreperous, that did not matter. The bread and butter could come from her side of the family.

She was about to pick up the phone and ring Romaleos to explain the plan to him when she remembered all six phones in the house were interconnected and that any snoopy servant could listen in on her conversation. So she scribbled a note to Romaleos, called her personal maid, thrust some money into her hand and told her to take a taxi to the Montagoulis house in Psychico and deliver the note personally to Romaleos.

Then she wrote another note to her father and left it in the downstairs toilet which she knew he always visited on his return home after the long drive from Piraeus.

When Romaleos opened the note, he read:

“My darling, my father has suddenly decided I am to marry that pimply creep Paris Spirakis and intends to announce the engagement at a party tomorrow. I am going to pretend I am committing suicide by sitting in his car after he comes home at 5:30 this evening, and running the engine in the closed garage. You must come and rescue me and then you will be a hero and we can get married. I shall start the engine of the Mercedes as I hear your Ferrari pulling up outside. Don’t be later than sixish or they may find me in the garage before you arrive.

Yours till hell freezes over,

Antzouletta”.

When old man Capulatos went into the downstairs toilet, he found a note which read:

“Darling Daddy, I know nothing can change your mind after it has been made up, but for me, marriage to Paris Spirakis would be a fate worse than death. So I have decided to take my life. When and where I shall perform my act of desperation you will find out in due course.

Farewell, father dear,

Your loving daughter,

Antzouletta”

While Romaleos was trying to reach Antzouletta on the phone to tell her to call off this silly and dangerous prank, Gerasimos Capulatos was ringing the police, the fire brigade and the Prime Minister’s office after the servants had searched the house thoroughly and found no trace of his daughter.

When the first squad car drove up with a screech of brakes, Antzouletta, sitting in the garage in her father’s Mercedes, started the engine and inhaled deeply. She thought Romaleos had anived.

When Romaleos did arrive, five minutes later, he rushed into the garage and found the love of his life lying on the front seat, looking quite dead. He switched off the running engine and laid his head on her breast, but could detect no heartbeat through her Maidenform bra.

“She’s dead,” he sobbed, “dead, dead, dead, oh my God, dead.”

With a cry of anguish, he slammed the garage door, lay down beside her on the front seat and switched the engine on again.

Not very long afterwards, they were discovered in the fume-filled garage and rushed to the KAT hospital in Kifissia.

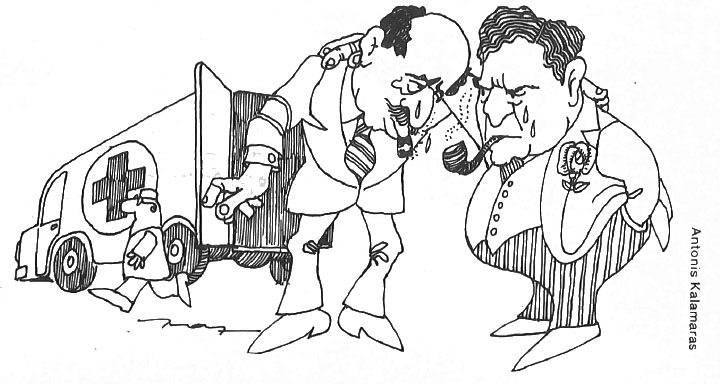

Outside the intensive care unit of that hospital, a distraught Capulatos and a frenzied Montagoulis were hurling insults at each other one moment and hugging each other, shedding copious tears the next.

“If my child is saved, I could find it in me to actually forgive you for your shenanigans, you Barbary pirate,” Montagoulis sobbed at Capulatos.

And Capulatos, in a moment of forgetfulness that he regretted later, said: “And if my child is saved, I’ll.

give you all the money I made from the oil I sold to – “

They were interrupted by the doctor who came out of the intensive care unit and said, with a puzzled frown on his face:

“Your kids will pull through. The girl will take a little longer than the boy, but they’ll be all right. But tell me something, have they lived in Athens a long time?” The parents nodded.

“All their lives,” they said.

“That explains it,” the doctor went on.

“By rights, their intake of carbon monoxide should have killed them. But I reckon by living in Athens all their lives, they must have developed an immunity to it. Yes; that must be it. The pollution cloud saved them. One could say that it’s an ill nefos that blows nobody any good!”