“My associate and I have just arrived in Greece and we have an interesting proposition to make to you,” said the voice on the other end of the line.

The English was heavily accented and I could not quite make out whether the speaker was an Arab talking with his mouth full, a Serbo-Croat with a speech impediment, a German with a Turkish mother or an Azerbaijani who had just taken a post-graduate degree at St. Antony’s College, Oxford. The accent seemed to contain all these elements.

“What kind of proposition do you have in mind, and why me?” I asked.

“We cannot discuss that over the phone,” the voice replied, “but if you want to know why we chose you, we can tell you we were most impressed by that drawing we saw of you in The Athenian. We recognized you at once as a strong, dominant and ruthless sort of person who will let nothing stand in his way. Just the sort of man we want.”

“That was a terrible drawing of me. I don’t look at all like that and, in any case, I have none of the qualities you are ascribing to me. Are you sure it’s me you want and not the publisher of The Athenian?”

“We are almost sure. In fact, the close-set eyes were the deciding factor. Can we meet and discuss this further?”

I thought it over for a moment and then my curiosity got the better of me. I was dying to find out what concatenation ot circumstances, what miscegenatory factors and what educational calamity had produced that abominable English accent. I was also curious to know what sort of proposition they were going to make.

They asked me to meet them in one of those sleazy bars off Omonia Square where tourists or hicks looking for a little frolic end up with a full-blown hangover and an empty wallet.

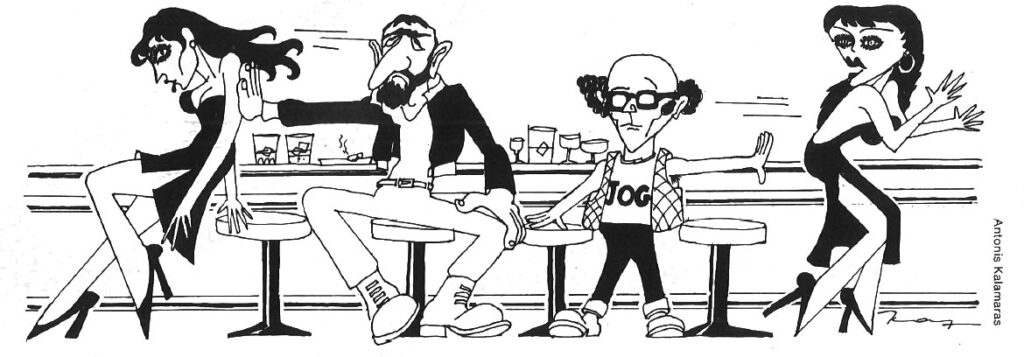

It was so dark in there I couldn’t make them out at first. Then I spotted them, sitting in a far corner of the bar and pawing a couple of girls who were protesting vigorously.

“No, Johnny. Not here, Johnny. You be good boy, Johnny. We do this later. You want another drink, Johnny? I want champagne.”

When they saw me, they pushed the girls away and stood up to greet me.

One of them was a tall, macho looking type with an unkempt beard, a long nose and gorilla-like arms. He wore a crumpled khaki wind-cheater, blue jeans and heavy walking boots.

The other was a small fellow with a bald pate and two shocks of frizzy hair standing out on each side of his head, thick-lensed glasses; thin, cruel lips and a dark, sallow complexion.

They looked as if they belonged to some international terrorist organization and I was not surprised when the first thing the tall man said to me as soon as we had sat down was: “We belong to an international peace and freedom organization.”

“How very interesting,” I said, wondering how soon I could politely take my leave of t1iem without being felled by a stiletto in my back or by a burst of gunfire.

“Yes,” the tall guy went on. “A very important organization that is going to change the course of world history. We have active cells in most of the capitals of western Europe and now that Greece is in the Common Market, we have decided we should extend “our activities to this country as well.”

The tall man stopped and lit a cigarette, waiting for his words to sink in, while the short fellow nodded gravely. As he talked, I was looking at his face, trying to work out his nationality and also trying to get at the root of that baffling accent of his. But with no success.

“May I ask what is the name of your organization, Mr. er – I don’t think I know your name, or your friend’s here,” I ventured.

The tall man smiled and shook his head. He patted my cheek with a hairy hand.

“We shall give you details and the code names we use only after you have heard and accepted our – proposition,” he said. ”We want someone in Greece to represent the organization ·primarily. Later, perhaps, to form a cell and recruit cadres and then undertake activities to promote our cause. It’s all very simple, really.”

“Yes,” I agreed, “nothing to it, is there?”

The tall man smiled and patted my knee this time.

“I knew we had the right man as soon as I saw that Kalamaras cartoon of you in The Athenian. My judgment has been questioned in the past, but this time I’m glad I’ve made a sound decision.”

“But wait a minute,” I protested, “you do realize, of course, that I have no experience whatsoever in this kind of thing, in spite of your excellent judgment”.

“Exactly,” the man said, extending one of his gorilla-like arms and clasping my shoulder.

“We don’t want anyone with set ideas and outdated methods. You will, of course, undergo a period of intensive training at one of our camps, at the end of which you will be a first-rate expert in skyjacking, kidnapping, knee-capping, blowing up cars, sending letterbombs, occupying embassies, shooting American ambassadors and Turkish consuls and all the rest of it. I am sure you will graduate from our .course summa cum laude. The stuff is there, I can see it in your close-set eyes.”

The other man, who had not said a word so far, cleared his throat and leaned forward.

“You will also make a great deal of money,” he said.

“Oh,” I exclaimed. “You will be paying me a handsome salary?”

The little man shook his head.

“Nothing like that,” he said.

“But with the training we will give you, you will be able to rob banks, kidnap rich Greek industrialists and hold them for ransom, work a protection racket – there are lots of ways to raise funds. Mind you, you won’t be allowed to keep all of it. A big slice will go to headquarters, then a percentage to our pension fund for retired terrorists. The rest will be to cover your local operational expenses, for which you will have to account in detail, and your emoluments. In a few years’ time, you should have a tidy fortune laid by – “

“If I am still alive to enjoy it!” I exclaimed.

“That reminds me,” the little man went on, “you will have to make a will leaving everything to the organization in case you should die of natural or other causes.” I shook my head.

“What’s the matter?” the tall man asked.

“It won’t work,” I said.

”What won’t work?”

“Robbing banks, kidnapping industrialists and that sort of thing.”

”Why not?”

“Because, for one thing, the tellers and the rest of the staff of Greek banks simply refuse to be robbed.

They know that whatever is missing from the till will be retained from their salaries and that they will lose all prospects for promotion, so they prefer to risk getting shot rather than hand any money over to a bank robber. Getting away is not easy either. Have you seen the traffic jams all over this city?”

“What about kidnapping rich industrialists?” I shook my head.

“Half of Greece’s industrialists are up to their necks in debt to the National Bank and the other half are so old, and have held onto the reins of their business for so long that their sons and heirs are dying to get them out of the way. So the prospects of ransom money from either category are very poor indeed.”

The dark little man turned and looked at his companion with an expression of disgust on his face.

“You made a boo-boo again, Wilfred!” he said, reproachfully.

The tall man closed his eyes and raised his head with a look of utter frustration on his face. He banged his gorilla-like fist on the low table in front of him and said: “Damn, damn! This was my last chance to redeem myself with the organization. What’s going to happen to me now?”

What happened to him then was that the bar was suddenly filled with cops who grabbed them, disarmed them and marched them out of the bar in the twinkling of an eye.

Before going to the appointment, I had tipped off a friend of mine in the Interpol office of the Security Police. The bar had been bugged and every word of our conversation had been recorded in a police van parked outside.

Next day, I called on my Interpol friend and satisfied my curiosity about Wilfred’s accent. He was indeed the illegitimate son of a Bavarian con-man and an Anatolian belly dancer, had spent his early life in Arab countries and been trained in a PLO camp, had later married a Serbo-Croat woman with a cleft palate and was now living in sin with a young Parsee girl who had taken a post-graduate degree in sociology at Oxford. I had been right on every count.