Movies, travel brochures, books, magazine articles and word-of-mouth descriptions have covered the subject pretty fully for them and the surprises, if any, are likely to be few and far between.

But think of the poor traveller at the turn of the century, steeped in classical studies and well-versed in the romantic literature of the eighteenth and nine “eenth centuries, who came to Greece, half-expecting to see people still wearing chitons and sandals and the country’s ancient monuments as splendid as they were in the time of Pericles.

Such a one was Louis Bertrand, a French writer who was born in 1866 and died in 1 )41. His first voyage to Greece is described in his book, “La Grece du Solei! et des Paysages”, which was first published in Paris in 1908.

His disillusionments were many, but in the end, halfway through his narrative and in the course of his search for Iphigenia in Aulis (he had read Euripides and Racine), he comes to a conclusion that could well point a moral to some of us who still bask in past glories and refuse to face the facts of modern life. But let Bertrand tell it in his own words:

By the somnolent rhythm of the train that was taking me to Euboea, I recited to myself the verses of the chorus sung by the women of Chalcis, in Euripides’ tragedy: “We came, skirting the sandy beach of seaside Aulis… ” From my window, I could follow the winding beach, count its pebbles and see, on the other side of the tiny bay, bathed in sunlight, the white houses of Chalcis, capital of the nomarchy of Euboea. At first, I gained the impression of a certain shabbiness at the sight of this celebrated spot. But it faded soon enough: already the legend of Iphigenia was beautifying Aulis for me! Indeed, even though I was reluctant to admit it to myself, I had only come here for her.

I got off at the station at Chalcis and climbed into an ancient, horsedrawn cab. Almost immediately, we crossed the Euripo Channel. This same Euripo which seemed so terrible in the alexandrines of Racine!

I had imagined a real strait, a foamy arm of the sea, ceaselessly churned by angry waves! And here I was, crossing it with barely ten turns of a carriage wheel. The Euripo Channel is simply an inlet, not larger than one of our canals and spanned by a swing-bridge of well-polished steel. At one end there was a cafe, with loungers already seated at its tables. At the other end, a hotel reared its imposing presence. I had forgotten Chalcis and Iphigenia. I was in one of our sub-prefectures of the North, on the banks of the Deule or the Scarpe.

To ease my conscience, I walked through the town. It looks like every other in the kingdom: It contains, as they all do, a plateia, a rectangular esplanade which is invariably called Constitution Square, a large number of cafes and many pharmacies. This is latter-day Greece – a new country with improvised market-towns of a utilitarian platitude which remind one of the colonies or of America. And, beneath this banality, one finds ruins that are often mediocre, admirable memories, but profoundly ensconced in the past and which it is not always easy to revive!

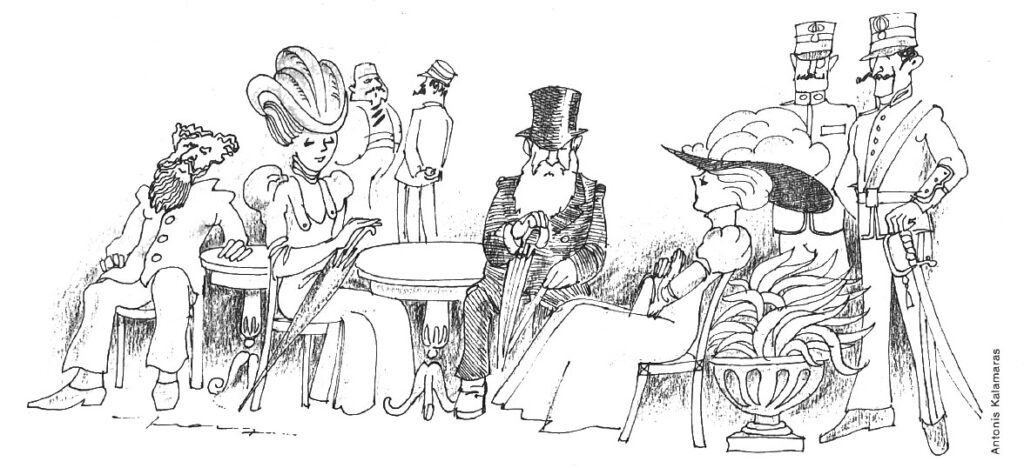

It was with these sad thoughts that I made my way back to my hotel – the Palirroia – named after the Euripo current. It was four o’clock. All the beau monde had crowded onto the hotel terrace which overlooks the narrow channel. I seated myself amidst the general curiosity. A khaki-colored suit, that I had unfortunately worn that day, provoked scandalized glances. I felt that my informal attire was being severely judged by the very correct public which surrounded me. There were lieutenants and captains, bedecked with insignia, dignified functionaries and the diplomatic corps as well, represented by a pot-bellied Armenian who is the vice-consul of Turkey. Beside me sat a family: the father, in deep mourning, engulfed in a black morning suit, with a cane, pince-nez, and a green umbrella between his legs; his two daughters, with elbow-length white gloves, wearing extremely attractive hats. Under their hat veils, I could see the loveliest brown eyes one could hope to find in this fair Hellas where they abound!

The two virgins, already past their prime, were considering the lieutenants with visible interest and then, feeling themselves observed, would quickly lower their slightly heavy lids over their beautiful, startled eyes and pretend to be listening to the band, which was playing at that moment an air from the Cavalleria Rusticana.

I must confess to bewilderment at finding myself in a bourgeois casino in Chalcis. I looked for Iphigenia amidst the women’s hats that bloomed all over the terrace and my gaze met that of my neighbor, the elder of the two daughters. A dark light crossed her black pupils that seemed to be saying: “O stranger, how ridiculous of you to be in pursuit of a worthless antiquity, this retrospective enthusiasm for a little princess who, perhaps, never existed! Of course, we are not princesses. But we too are Greek. My sister is called Antigone and my name is Iphigenia, like the one you seek and like her, too, we want to marry well. But Achilleses are rare, O stranger. Come on, look at us, we are worth more than the old stones you admire and the superannuated fables which dazzle you!”

This silent speech convinces me and I begin to find my disappointments stupid. Am I, like a pedant, to be shocked by all that is modern and gape like a ninny at the fact that Chalcis, the town of Arethusa, is full of pubs and apothecaries? Eh, what? Because the contemporaries of Agamemnon once waged war on Troy, must we forbid their descendants to exist as we do? The Greece of yesteryear was far superior to what it is today, that is true. But the new Greece has a very great advantage over the old. It is alive, while the other is dead!