His name is Trofim Trofimovich Ripser-Korsetsov and he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1914 for his devastating expose of Russian cat houses from the far reaches of Outer Mongolia to the Pripet Marshes.

Although his book earned him the coveted prize, it also earned him the displeasure of the imperial court. The Tsar and the entire Russian aristocracy never forgave him for revealing the closely-guarded secrets of the country’s vast network of sporting establishments in the now-famous “Kwiki Archipelago”.

Indeed, they made life so difficult for poor Trofim that he was forced into exile. He made his home in Athens where he lived in style for several years on his prize money. When that ran out, he married Madame Hortense Kanilingskaya, a notorious procureuse from Odessa who had fled the Bolsheviks on a Greek tramp steamer and arrived in Piraeus with several thousand gold sovereigns in her baggage.

When I met Trofim at the VD clinic, which had been largely financed with a generous grant from Madame Hortense in memory of the gallant Greek seamen who had saved her from the Reds, he had given me his card and invited me to visit him and his charming wife at what he called his ‘chateau1 on the Tatoi road in Kifissia. But what with one thing and another I never got around to it.

Now, I decided, it was time to look him up and find out why a famous person like him had not appeared at any of the functions to celebrate the Elytis event and the Onassis awards. I could not remember the address in Kifissia but I knew I had kept his card. I ran up to my attic and began rummaging through three trunkfuls of mementos. In the second trunk, with a cry of triumph, I fished out his card which I found wedged between an autographed photograph of King Farouk and a slipper worn by Maria Callas at her first performance of La Boheme at La Scala di Milano.

Trofim had been twenty years old when he wrote the ‘Kwiki Archipelago so now, if he was still alive, he must be eighty-six.

It was early afternoon when I walked up the marble staircase of an old and imposing mansion and rang the bell by the great oaken door. After what seemed an eternity, I heard footsteps behind the door and the rattle of a chain being drawn. The door opened an inch and I beheld an aged retainer in a winged collar and tie and a green baize apron. I gave him my card and I was shown into a great hallway, hung with rich draperies and priceless Persian rugs.

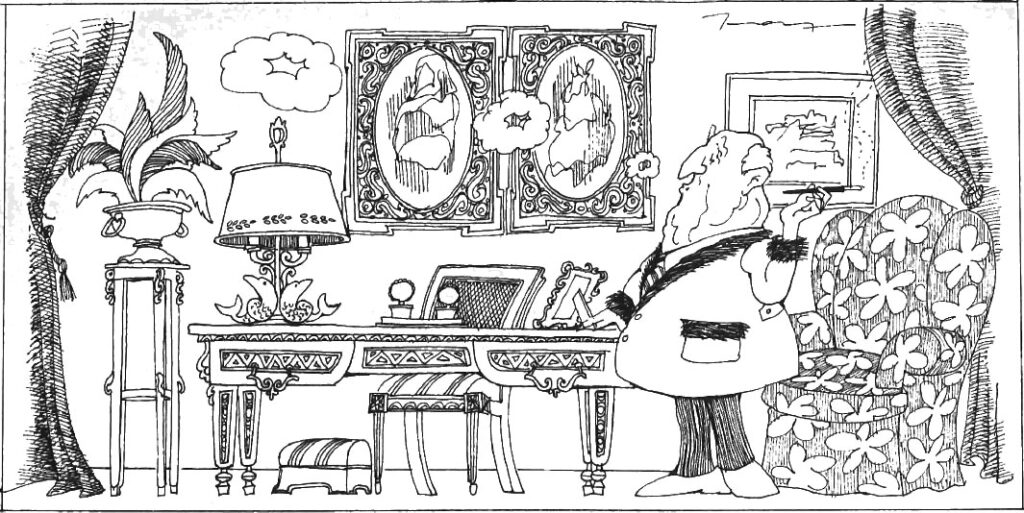

The retainer disappeared behind the draperies and a few minutes later he came back again and asked me to follow him. He led me into what appeared to be a study and, standing inside with my card in his hand was none other than the great man, Trofim Trofimovich Ripser-Korsetsov.

It was a moment that will remain indeliby carved in my memory.

In spite of his great age, he held himself erect and shook my hand with a firm grip. He wore a fur-trimmed smoking jacket and the cigarette burning in the long holder he held elegantly in his left hand was sending a blue plume of smoke curling up around his clean-cut features and his penetrating grey eyes which were gazing at me intently.

“Alexei”, he exclaimed, stepping forward and embracing me. “Trofim,” I cried, returning the embrace.

“After all these years.”

“Yes, after all these years.”

Then he stepped back and looked a little puzzled. “Have we met before?” he asked.

“Of course, at the VD clinic in 1949,” I prompted.

“Ah, yes. The VD clinic. What a memorable experience. It was poor Hortense’s pet project. How could I have forgotten. You must forgive me, but I am growing old.”

“Not at all,” I said cheerfully. “You don’t look a day over eighty-five. And Madame Hortense, she is, er —” I stammered, fearing the worst.

Trofim nodded his head sadly. “Yes, I’m afraid she’s no longer with me. She left me ten years ago to live with a sponge fisherman from Kalymnos. For all I know, she’s still with him, sitting on a caique off the north coast of Africa, stringing sponges on a line.”

After we had settled comfortably in deep armchairs and were sipping tea from a magnificent samovar in the center of the room, I asked Trofim why he was living in such seclusion and why he had not written anything since his masterpiece in 1914.

“Well, you know how we Russians are.When we can no longer stroll along the Nevsky Prospekt or gallop through the tall fir forests of Siberia or sing in chorus with a bunch of boatmen on the Volga, all the life seems to go out of us,” he explained.

I nodded sympathetically. “You felt spiritually castrated,’ I ventured.

“Spiritually, yes. But not in any other way, mind you. That Hortense knew every trick in the book and then some. A truly insatiable woman and I’m glad to say I never gave her cause for complaint. But she always had a secret longing for a younger man and when this sixty-five year-old sponge fisherman turned up, she just went crazy over him. Women are such strange creatures, aren’t they?”

I nodded in agreement.

“So when she left me I decided to go back to writing.”

I looked up eagerly. “That is a sensational bit of news, Trofim,” I said. “What have you written? When is it going to be published?”

“Well, you know that Hortense’s work in Odessa obliged her to maintain contacts with the best establishments all over the world. There was a constant va-et-vien of choice stock from one house to another and when Hortense left, 1 found her address book with a very long list that covered the whole of Europe, North and South America, Africa and the Far East. So, for the past ten years, 1 have been travelling to all these places, gathering material for my new book.”

“Splendid, splendid!” I exclaimed. “And when will it be finished?”

“I have two more trips to make — one to Tierra del Fuego and another to the Andaman Islands, after which I shall have covered the subject in its entirety.”

“And what are you going to call your new book?”

“Why, ‘The Universal Kwiki of course.”