By a very small stretch of the imagination it becomes easy to speculate on what would happen if “the great God of Greece”, who has intervened so many times in the past to save the country from disaster, should “put his hand” once more and uncover such a vast reservoir of oil that Greece would become, overnight, the wealthiest country in the world.

And what would the Greeks do with the petro-dollars that would come flooding in, to fill the Treasury and bank vaults to bursting point?

For one thing, they would buy large parcels of stock in practically all of the major manufacturing companies in the Western world and, with the head start they already have in shipping, would eventually control every aspect of the world economy, from the purchase and transport of raw materials to the production, sale and shipment of finished goods.

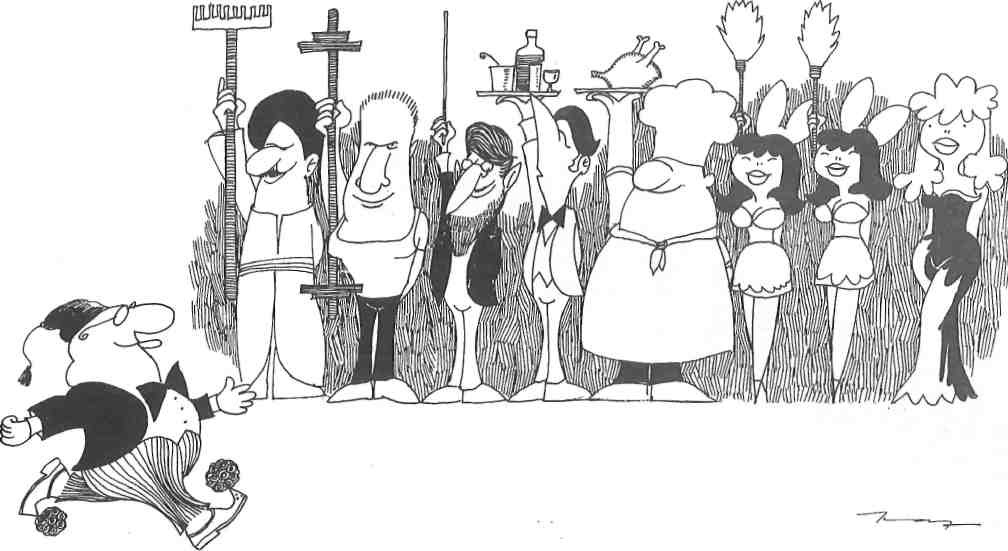

The change in life-style would also be spectacular. A six-car garage for every home (a Rolls for the husband, a Cadillac for the wife, a Lamborghini and Ferrari for the kids and two Aston Martins for guests); an Olympic-sized swimming pool in every garden, filled with Loutraki water; a giant, transparent water bed, filled with tropical fish and covered with sheets of the finest Chinese silk and a Bayeux tapestry for a counterpane; a bathroom with floor and walls of solid gold and a sunken bath made of platinum with diamond-studded taps spouting lavender water and asses’ milk and a bidet spraying three kinds of French perfume, including “Je Chatouille” by Lanvin. A living room with a huge fireplace stoked by inflated European currencies and a wall-to-wall carpet of giant panda skins; the walls covered with priceless paintings the curators of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre would give their right arms to possess; a refugee Persian gardener in the grounds; a Swedish masseur in the gym; an Italian maestro in the music room; an English butler in the pantry; a French chef in the kitchen; Filippino maids all over the place; a German governess in the nursery and a full-time marriage counsellor in a back room for instant solutions to domestic problems.

Every Greek would have two yachts. A smaller for Aegean cruising and a larger one for winter holidays in the Caribbean or the South Seas. Part of the winter would be spent at Davos or St. Moritz where he could show off his gold-laced crocodile-skin ski boots and his wife her chinchilla-trimmed sunglasses and mink ski pants. Part of the summer, also, he would spend in that charming retreat in the Himalayas, bought for a song from a destitute sherpa and converted into a replica of the paradisaical lamasery featured in Lost Horizon. For photographic safaris in East Africa he would engage Stanley Kubrick or Francis Ford Coppola to do the filming with spliced shots from King Kong for laughs.

And while the Greeks would be living high on the hog, what would their Government be doing? It would be solving the Cyprus problem by giving the Turks on the island a million dollars each and inviting them politely to buy a one-way ticket to Anatolia. It would be carrying out delicate negotiations with the Albanians for the purchase of Northern Epirus and dangling before Turkey the enticing offer of two oil wells off Kavala in exchange for Eastern Thrace.

At the same time, in a closely guarded back room at the Foreign Ministry on Zaiokosta Street, a team of historians would be marking out on a map the limits of the Byzantine Empire in its hey-day and another team of experts on international law would be working out how best to lay claim to these territories on the grounds of historical precedent.

And in order that nobody should accuse the Government of the world’s wealthiest country of lack of foresight, another extremely hush-hush team in the Defence Ministry would be poring over ancient maps borrowed from the Gennadius Library showing the extent of the conquests of Alexander the Great.

The smaller countries on Greece’s perimeter would begin voicing fears in the United Nations that Greece was embarking on a perilous course of territorial expansion and asking for a vote of censure. The Russians would then drop hints that caviar shipments to Greece from the Caspian might be curtailed and the French would imply, in diplomatically couched language, that the EEC Commission might impose countervailing charges (whatever those may be) on exports of pink champagne to Athens. The Greek delegate to the U.N., in reply, would hold up the prospect that the life-giving flow of oil from Greek pipelines to the West might be suspended for a time while “essential repairs” were made to certain pumping stations. Then everybody would back down after assurances had been given by President Brademas of the United States that Greece had absolutely no territorial aims in Asia but was merely anxious to continue the work of Alexander the Great in extending the benefits of Greek culture to that area. He would add that there was absolutely no foundation in the charges that the Dora Stratou folk dancers, singers like Bithikotsis and Kokkotas and poets like the Nobel prize-winner Odysseas Elytis, now touring Syria, Iraq, Persia and Pakistan were spies. He would say he had been reliably informed by his CIA agents in the area that the Minox cameras and microdots that had been found concealed in a bouzouki by an inquisitive chambermaid in a Tabriz hotel had been planted there by a scheming belly-dancer intent on framing the Greek Cultural mission.

Greece would continue riding this crest of power and prosperity until the first decade of the 21st century when nuclear and solar energy would be harnessed sufficiently to replace the world’s reliance on oil.

But although solar energy would be used extensively in countries with temperate climates, nuclear energy would have to be the main standby of the industrialized nations of the cloud-covered north.

And at this crucial turning point in the world’s economic structure would it be too much to hope that the “great God of Greece” might step in again — with the discovery of immense uranium deposits in the Ouranopolis area of the Halkidiki peninsula?