translated by Grace Edwards

He was born in Monemvasia, a small town on the southeast coast of the Peloponnesus, already laden with myths. There the modern houses are built beside the ruins of the old medieval city. The spot is inspiring, a barren rock rising above the usually turbulent sea and surrounded by a wall which once protected the city.

Youngest in a family of four children, Ritsos was born to a once wealthy landowner in a mansion filled by the shades of famous ancestors. The times were crucial. On the eve of the Great War, an era was coming to an end and a new one was beginning. For Greece, the Balkan wars and the agricultural reforms of Venizelos were changing the structure of society. For the Ritsos family it was a time of personal crisis. It hastened economic catastrophe and caused the disintegration of the family. Thus, the earliest childhood experiences of the poet were to be marked by the final echoes of falling splendour and by a pervading climate of decay and irreversible catastrophe. Greater personal disasters followed one upon another: The poet’s father, and later, a sister went mad. One of his brothers died of tuberculosis, and then his mother.

The young Yiannis Ritsos attended local schools and then, as a very poor boy from the provinces, he came to Athens to try his luck. Meanwhile, he too contracted tuberculosis.

The years which followed were divided between searching for work and periodic stays in various sanitariums and nursing homes for needy patients. Within these sanitariums with their inhuman living conditions — which he exposed publicly in a letter in 1930 — the poet’s revolutionary ideology gradually took shape. From then on it was to hold first place in his work and in his life.

In 1931 he joined the Communist Party (K.K.E). Meanwhile he worked as a typist, an actor, a dancer, and as a proof-reader in a publishing house. From 1934 he started issuing his first books of poetry and from 1936 both he and his work began attracting persecution. Under the dictatorship of Metaxas, copies of his poetic lament Epitaphios were publicly burned. In 1942 he joined the National Liberation Front (EAM), but he became seriously ill once again and his friends took up a collection to save him. Since this was a period when the Greek people were dying of hunger, Ritsos refused to accept the money and asked that it be divided among the members of the Society of Greek Writers.

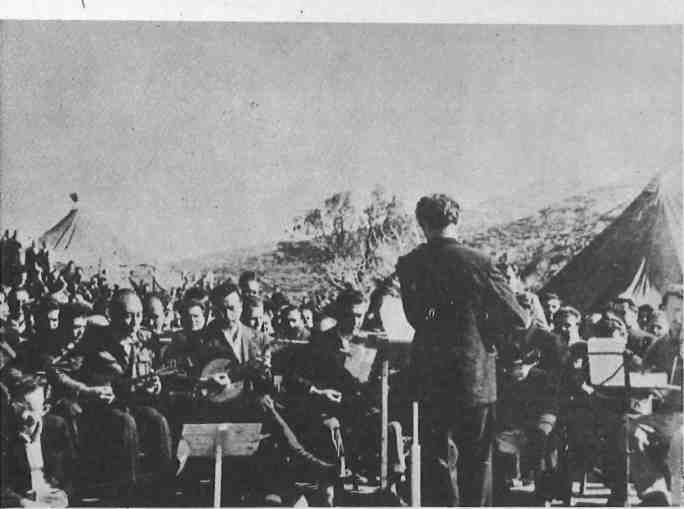

During the Civil War in the winter of 1945, he joined the guerrillas of ELAS, The National Popular Liberation Army, which withdrew from the capital in order to concentrate in the north of the country. In the provinces Ritsos took part in the guerrilla ‘theatre of the people’ which was active throughout Northern Greece.

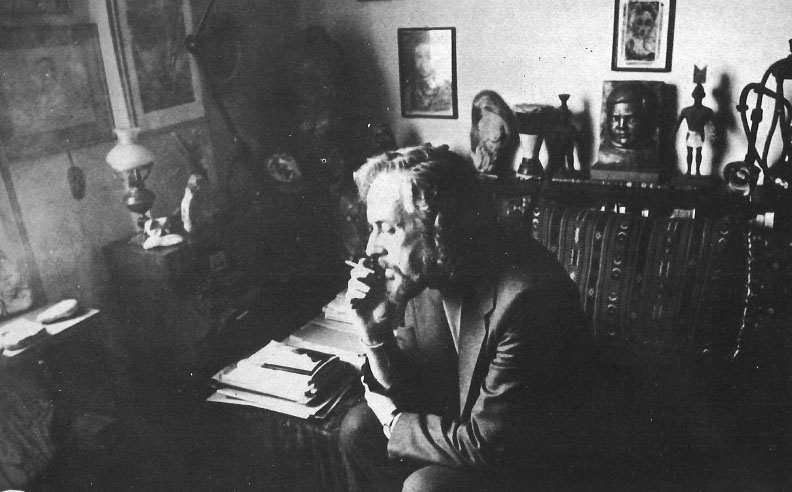

During the years 1948-1952 he was a political exile on Makronisos and other islands of detention. However, he never abandoned his work. He was later to present an impressively large collection of poetry, as well as paintings which he created unceasingly in whatever medium came to hand and — on the islands of exile where there was nothing else — on pebbles, bones, roots. It was not until 1956 that he won official recognition when he received the First National Poetry Prize for his poem ‘The Moonlight Sonata’. In the meantime he traveled and translated poets of other countries into Greek.

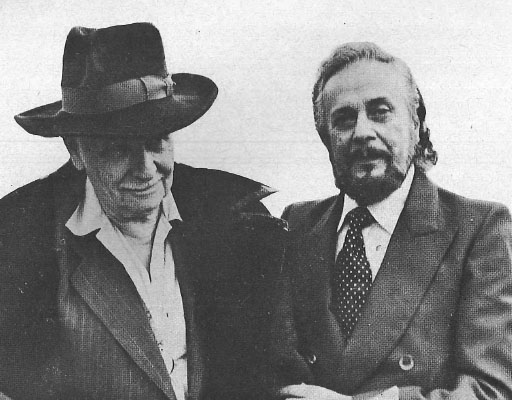

Gradually he began to gain recognition abroad. The French poet Louis Aragon became enthusiastic over his work to such a degree that he did not hesitate to call him “the greatest living poet of our time”.

In 1967 Ritsos was arrested by the Colonels’ dictatorship and again taken to prison and exile. He was now very ill once again and concern for his release developed abroad. Meanwhile his latest poems were smuggled out to France where they were published under the title Pierres, Repetitions, Barreaux. In 1970 he was proclaimed a member of the Academy of Literature and Science in Mainz, West Germany. Two years later he received the Grand International Prize for Poetry at the Biennale of Knokke-Le Zoute, Belgium. In 1974, he won the Bulgarian International Prize, ‘Georgi Dimitrof’. In 1975 he was declared honorary doctor of the Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki and won the French ‘Alfred de Vigny’ Prize. In 1976 he received the Italian ‘Etna Taormina’ and ‘Seregno Brianza’ Prizes. And in 1977 he received the Lenin Peace Prize.

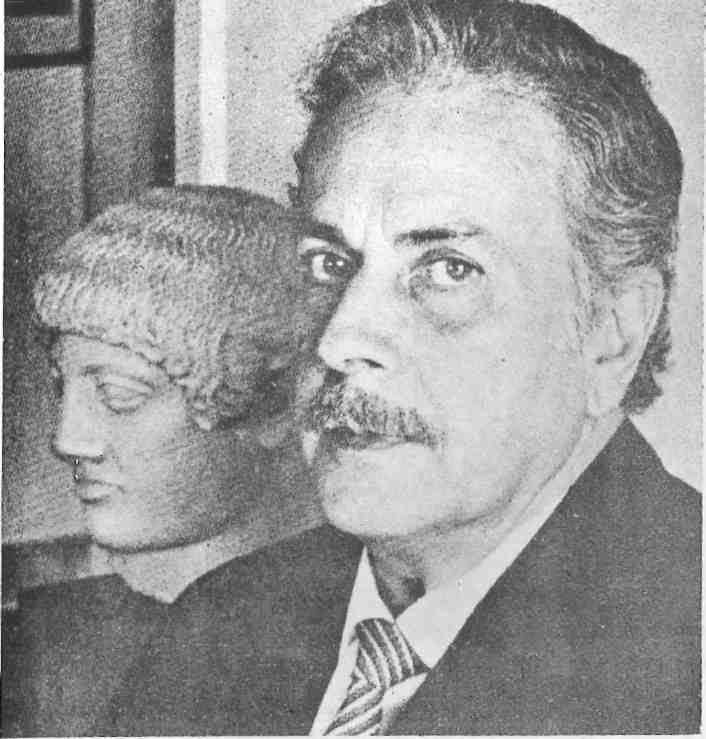

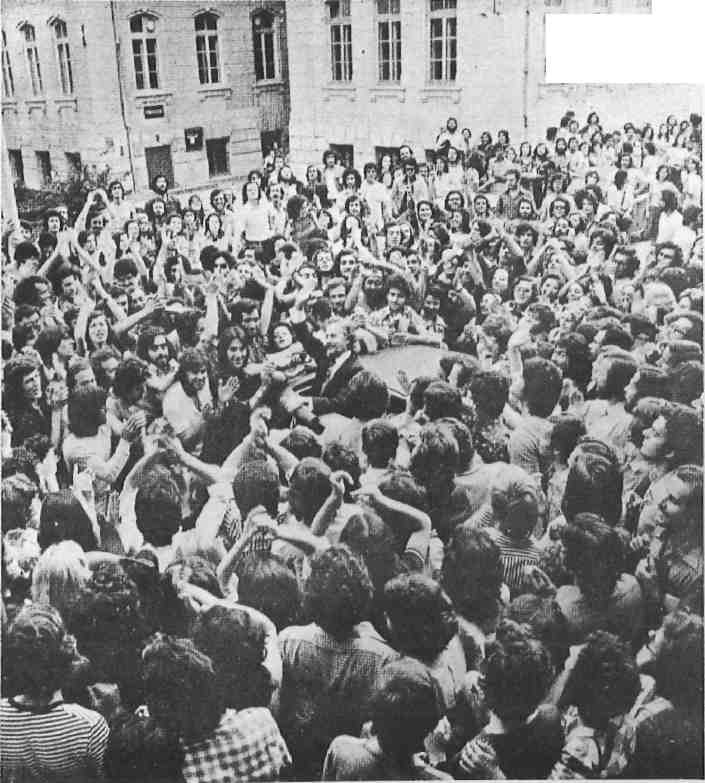

Now in 1979, his seventieth birthday is being observed. In Greece a large number of recitations and exhibitions of his works have been organized with great participation on the part of the public. Celebrations are also taking place in many parts of the world and articles are being published in Cyprus, the Soviet Union, France, Bulgaria, Romania, England, and Denmark. The Supreme Soviet of the USSR has awarded him the order of “Friendship of the Peoples”. Yet surely the most significant event and the greatest honour for the poet must be that, on the anniversary of his seventieth year, his books are translated throughout the world, and that in his homeland they have reached astounding peaks of circulation. Epitaphios, for example, is now in its thirtieth edition.

To approach a body of work so extensive in size and so varied in meaning as the work of Yiannis Ritsos, is certainly no easy matter either for the general reader, or for the student of his work.

Both scholars and biographers agree, however, that the elements of myth play a primary role in the work of the poet. Yiannis Ritsos, whose relationship to myth began from the moment of his birth in Monenvasia later sought to express himself in myth. “In his poems,” writes the scholar Gerard Pierrat, who is also Ritsos’ biographer, “the ancient liturgies are thrown together with Byzantine legends and the exploits of the klephtes and rebels. An eternity of slavery from which springs an eternity of resurrection. The atmosphere is charged, pierced by the dark hope of the desperadoes who wait glued to their rifles. A flaming animism pervades each line, awakening landscapes of Greece one after the other, throws them into the struggle, raises up the islands, the wind, the sea, and stirs up in one general tumult men, animals, elements, even the dead who keep vigil just as the guards of Byzantium once did on the borders of the empire.” “From where does this poetry come?” asks Aragon in his article “Pour Saluer Ritsos”. “Whence comes this shudder, where things as they are play the role of phantoms, where the Greek Hamlet no longer comes face to face with dead kings, and the new Oedipus no longer comes face to face with the Sphinx but with treacherous, familiar things?”

Nevertheless, this myth-creating element in the poetry of Yiannis Ritsos has a very special character which cannot be ignored without destroying the whole meaning. “The poet”, writes Peter Bien, “can employ mythical subjects nonchalantly with no fear whatsoever of restricting his audience to highbrows or of deserting contemporary reality for either some fantastical vision of the past or some disinterested quiver of esthetic appreciation… Yet to accuse him of u failure of nerve because of this, or of a retreat to non-historicity and universalism, would be unthinkable. On the contrary, Ritsos’ mythic poems are so firmly moored to his nation’s and his own contemporary, specific experience that they do not cut loose from that experience when the winds of ancient legend puff out their sails. Myth leads his work neither to evasion nor diversion, but to revelation.”

Thus, all this mythology, which is born within the work of the poet, in the end functions revealingly. And the revelation concerns, of course, the actual face of contemporary Greece which is hidden behind the tourist myth and the supposedly Greek character of the type of Zorba, and the like. In Ritsos the actuality of Greece is projected naked in a way not at all appealing to the eyes of the foreigner who comes to enjoy the sea, sun and Mediterranean hospitality; who has no wish to imagine that the islands of the Aegean have been used for exiles, that in the shadow of the Acropolis men have been tortured for their ideas, and other such unpleasant things. Here we have, then, the apparent paradox and the amazing phenomenon: the myth which leads to a great, unmythical poetry.

Something further which must be noted in order that we be not deceived in regard to the actual function of the myths of Yiannis Ritsos is the great role played in his work by detail. We might say that the greatest meanings derive from details, from everyday insignificant activities. Yet, these activities are what, tile by mosaic tile, give reality to everything that is known and familiar, which again is nothing more than the actual face of modern Greece. Sonia Ilinskayia writes: “Inanimate things — houses, furniture, clothing — take on a special importance and, acquiring the gift of speech, each plays its own role, causing sequences which determine not only the feelings of the active personae, but also the direction of the reader’s search for truth, and the ultimate meaning of life.”

All this, however, constitutes an enormous gift of the poet to his homeland. “Ritsos,” the critic Nora Anagnostaki suggests, “has done with his poetry what Proust did for prose: with his regenerating remembrance, he creates for us the consciousness of being within Greek space. This is why Ritsos is such a great poet, and precisely why he is a national poet and not a ‘militant’ one.” Gerard Pierrat has written: “The perception of being Greek which Ritsos endows with universal radiance loses, thanks to him, any connection with the old cliche of the ‘Greek spirit’ and of the ‘Greek miracle’. We may define this perception more of less by its refusal to be defined or classified. It is simultaneously a painful devotion to the tribulations and the sacrifices of the past and a renewed quest, a slow and sensitive approach to the secrets of the world.”

Let us leave, however, the field of studies. How great a poet Yiannis Ritsos is, and what his contribution to poetry is, will be judged by the future, when both the laudatory and the unfavourable reactions to his work will be seen more clearly. What is indisputable and timely is that Ritsos has become a beloved poet as well as a popular hero. Without underrating the role played by the melodic cadences of Mikis Theodorakis, who has set so many of Ritsos’ poems to music, it is nevertheless an achievement that Ritsos has produced poetry of a kind to be read by the general public.

It may be possible to find a young worker who knows nothing about Yiannis Ritsos. However, it is totally unlikely that you will find such a worker in the area of trade-unionism. From the moment that people begin taking an interest beyond their work, which means that they will read a few books, it is almost certain that one of the first of these will be a collection containing poems of Yiannis Ritsos.

In their trade union headquarters, we talked with a car repairman, a bookkeeper, a mechanical engineer, a pharmacy employee, and a hotel employee, and this is what they said:

Vasos: I began with the songs of Theodorakis. Later I got interested in reading the poetry. Of course I don’t have enough time, but I read him. He gives us expression, he expresses the feelings of the people, our own problems.

Aleka: I have also read books about his life. He expresses my own problems which are mixed as much with joy as with sorrow. He makes life real.

Nikos: What Ritsos writes, that’s the way we live.

Vasos: He doesn’t let you forget. He makes you remember. He opens up horizons for you.

Ourania: I read the poem first. Later I heard the song. He troubles you, and then he revives you as a person.

Eleni: I started reading him in high school. And if I didn’t understand him sometimes, it was because I wasn’t familiar with the things he was writing about. Every word of his refers to the popular movement: With Ritsos you read the history of a people… I grew up in the provinces where there wasn’t any way of getting ahead. In the books of Ritsos, of Seferis, of Elytis, I got in touch with a progressive world. For me poetry has a magic which prose doesn’t give me. The search within the line, to see exactly what it means, is what I like…

Nikos: You have to keep looking. He raises questions for you, he makes your mind work.

Ourania: And if you don’t understand him with your mind, you’ll feel him with your heart. He is your own man, a companion who holds you by the hand.

Eleni: He uses a language which is spare. When I read Ritsos the paintings of Theophilos come to mind.

Nikos: We love him as a man and as a poet. You can’t separate the two.

And now let us go to a different area, to a newspaper. Katerina and Nikos are journalists of the younger generation. And both dislike Ritsos. At least, they say he is not among their favourite poets.

Nikos: This doesn’t mean, of course, that there aren’t several of his poems which I like. For instance, the ‘Moonlight Sonata’ I like a lot, as I do ‘Eleni’. I like Ritsos when he writes tender poetry. I don’t like his political poetry. I find it strident. I don’t like his work of the last few years.

Katerina: I don’t know how to say it, he doesn’t suit me… I find him somehow ‘saccherine’ and somewhat overblown.

Nikos: All the same, the wide circulation of his books is an established fact. He educates the people, and he brings one closer to poetry. Someone who reads Ritsos will later read another poet.

Katerina: He has a radiance which certainly cannot be separated from his political position. I remember once I worked in a print shop. There were thirty working-class girls there, with no literary interests. We printed a lot of books. The girls had tried reading them but nothing interested them. When we printed some books of Ritsos, suddenly they all came and wanted to get hold of a copy.

On the one hand: radiance, international recognition, the plaudits of critics who want to find in him the universal poet; on the other, the duty he feels to keep consistent with an ideology which marks his life; above all, the sentimental response of the simple people who want him to be “the companion who holds you by the hand”, who see him as a popular hero.

I don’t know how he achieves these things. I don’t know whether he achieves them. I can only think how difficult it is… to be making, continually, a dizzying attempt, to be walking constantly on a tightrope. It seems to me a very heavy weight to lie on the shoulders of any man, especially on one who has completed his seventieth year…

And truly I ask myself, what is he like — not the poet, not the “myth in life” — but the person who has celebrated his seventieth birthday with the prominence of such an exacting public life focused on him? What is the moment like when “they turn off the lights on the stage”? What then will support him?

The answers to these questions are not easy. What distance will be permitted between the ‘public’ person and the ‘private’? Those who know him find it difficult to answer. And it is possible that he himself doesn’t know. From one point on they are all inseparable: man, poet, fighter, celebrity, friend…

Nikos Margaris, a musician and the author of the book History of Makronisos, met up with Ritsos on the island of Ai-Strati where the exiles had been brought from Makronisos in 1950. He writes: “After an international outcry, the measures were relaxed and we exiles were able to make for ourselves more human living conditions and even to organize cultural events with which to fill our lives to some degree. Ritsos, like the rest of us, I remember, lived in a dormitory tent with eight to ten others, but he also had his own little hut, one of those which we had built ourselves and had assigned to him. He stayed there closed in for as many hours as he could and wrote or painted. He came to take part in our cultural activities and, I remember, he played the mandolin beautifully, beautifully… In the first quartet that we made up, Ritsos played first mandolin. Later he taught folk dancing, dances from all over Greece. He was courteous and soft-spoken with everyone, but somewhat unapproachable, somehow closed in on himself. His friendships were with very few…”

Gerard Pierrat remembers him, around 1960, relating memories from his younger years. Memories which resembled myths — characteristic of the climate within which the poet grew up — are those which perhaps gave the first support to the myth-creating function of his work at a later stage.

In those days, in Monemvasia, tuberculosis was something shameful. Often, when a person came down with it, his relatives closed him up in the house, in order that it not be known, and he never saw the world again. The young Ritsos, still healthy, couldn’t resist the temptation to accept a golden box given him by two tubercular girls. But that, in accordance with the superstitions of the time, was equivalent to a curse. His mother, crying, threw the box into the sea to exorcise the evil influence — which nevertheless came later to take its portion from the family…

But the Ritsos household was struck by another curse: madness. The father, in an insane asylum a short while before he died, ordered his son to empty the cisterns of the house in order to find his dead mother’s wedding ring. He thought this was the raving of a sick man and paid no attention. Later, however, when the cistern was emptied, the wedding ring was found there…

The author Stratis Tsirkas has a memory of Ritsos which he tells with emotion and gratitude which gives, as well, a measure of how deeply rooted is the poet’s sense of obligation: “It was around 1952 when we met at the house of friends. I, for reasons of my own and from discouragement, had stopped writing and believed that my connection with literature had definitely ended. Ritsos became furious when he heard it.

‘But do you think we have the right?’he said. ‘We owe ourselves to literature. What we have, we are obliged to give. Up to death we must fight and learn to overcome obstacles.’ I began to write again,” continued Tsirkas, “and I haven’t stopped since…”

Perhaps, however, something more revealing of the human side of the world of Yiannis Ritsos is this: His friendship with Stamatis Tzianoudakis, who is a lawyer, has been one of the closest in the poet’s life. They became acquainted under the most unpromising conditions for human relations: At Ai-Strati, Ritsos an exile and Stamatis a guard. Nevertheless the common need for kindness and communication which two human beings can feel succeeded in overcoming walls of dissension and hatred, which propaganda and opportunism had erected. Stamatis brought him cigarettes secretly, at his own risk he did everything possible to ease the poet’s life. Ritsos wrote a poem about him: “The Presence of Man”. And their friendship, which became firm during those difficult days, like a symbol of humanity has remained alive from then until today.

From Romiosini – Translated by KlMON FRIAR

They pushed on straight into dawn with the disdain of hungry men,

a star had thickened in their motionless eyes,

they carried on their shoulders the stricken summer.

The armies passed through here with banners clinging to their bodies,

with stubbornness clenched between their teeth like an acrid pear,

with the moon’s sand in their heavy army boots,

with the coaldust of night sticking in their ears and nostrils.

Tree by tree, stone by stone, they passed through the world,

passed through sleep with thorns for pillow.

They brought life a river cupped in their parched hands.

At every step they won a league of sky — to give it away.

At their outposts they turned to stone like scorched trees,

and when they danced in the village squares the ceilings in the houses shook

and the glassware clattered on the shelves.

Ah, what songs shook the mountain summits!

Between their knees they held the platter of the moon and ate,

and squashed an Ah in the depths of their hearts

as they would squash a louse between their coarse fingernails.

Who will bring you now a warm loaf of bread in the night that you may feed your dreams?

Who will stand in the shade of an olive tree to keep the cicada company lest the cicada fall silent,

now that the whitewash of noon paints the low stone wall of the horizon all around,

obliterating their great and virile names?

This earth that smelled so fragrantly at daybreak,

the earth that was theirs and ours — their blood — how fragrant that earth —

and now how is it that our vineyards have locked us out,

how has the light thinned out on roofs and trees,

who can bear to say that half are now under the earth and the other half in chains?

Though the sun waves you good-morning with so many leaves and the sky glitters with so many banners,

these lie in chains and those under the earth.

Be silent, the bells will ring out at any moment.

This earth is theirs, this earth is ours.

Under the earth, in their crossed hands

they hold the bell rope, waiting for the hour, they do not sleep, they never die,

waiting to ring in the resurrection. This earth is theirs and ours — no one can take it from us.

—