To say he was in uniform would be misleading because all he wore was a loin-cloth and brass rings round his neck *and ankles. When I asked him to sit down, he laid his ox-hide shield and spear carefully on the floor beside him and removed a small packet wrapped up in a dried banana-leaf frpm under the loin cloth.

“I have a tape here,1′ he said, “that I think will be of considerable interest to you. Would you like to buy it?”

“That all depends,” I replied cautiously, “what is it about?”

He shifted uneasily in his seat and looked around him furtively to make sure no one else was in the room. Then he bent close to my ear and whispered: “You must promise me that you will never breathe a word of this to a living soul. The lives of several people, including my own, may be at stake.”

“Okay,” I nodded, “I promise. Go ahead.”

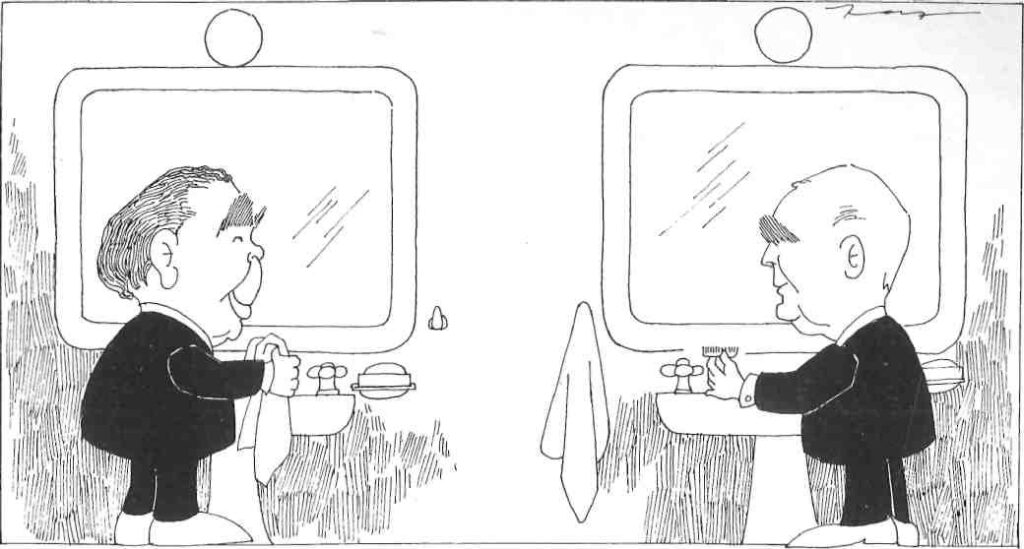

“Some time ago, our legation in Moscow succeeded in bugging one of the washrooms next to the main banqueting hall in the Kremlin. We thought we would obtain very interesting material in this way but aside from various snorts, gargles, throat-clearings, people hummirfg “Moscow Nights” or the “Song of the Volga Boatmen” and other unspeakable noises followed by the sound of flushing toilets, we never got a single word on our tapes.”

“That’s too bad,” I said sympathetically, “why do you think nobody spoke in the washroom?”

“I suppose,” the dark gentleman said, “because nobody knew who was behind the closed doors of the toilet booths. However, on the second of October, we struck gold.”

I pricked up my ears. “What did you get?” I asked.

“Brezhnev and Karamanlis went in there to wash and brush up before attending the banquet in Karamanlis1 honour and every word they exchanged is here on this tape.”

I gave a long, low whistle. “That is quite remarkable. Very interesting indeed. And you want to sell me this tape?”

“Yes,” the dark gentleman said. Then he lowered his head and looked intently at his dusty toes. “I need the money very badly,” he said, in a low voice.

He then explained to me that the President of his country, who was his minister’s third cousin twice removed, had been overthrown in a coup. The minister had been recalled but instead of going home he had flown to Paris to join his cousin in exile and had taken all the legation funds with him.

“I spent my last few drachmas on a koulouri and a sliver of cheese this morning,” he said, almost tearfully. “If I don’t sell this tape I shall starve.”

“But surely there are other people who would be more interested in the tape and who could pay you much more for it!” I exclaimed.

He shook his head. “I tried the CIA. They told me they’ve had a bug in that particular washroom since 1956 and that anyway they pick up all the conversations in the Kremlin by satellite. I tried British Intelligence but they said it was a rather nasty trick to pick up conversations in lavatories and they would have nothing to do with it. Finally, I tried the Turks but they could only pay me in Turkish lira and you can’t change those in Greece. So I’ve come to you. Perhaps you could use it in The Athenian?”

“I don’t think The Athenian could pay you very much for it,” I said dubiously, “although, of course, your interest is very flattering.”

“Look,” he said, “you listen to the tape and pay me whatever you think it’s worth. I’ve simply got to eat today. My tummy’s beginning to rumble already.”

I felt genuinely sorry for him so I agreed. He unwrapped the tape and I threaded it through my tape recorder. This is what I heard:

“Well, Gospodin Karamanlis, how are you enjoying your visit to Moscow?” “Very much, Mr. President. I was particularly impressed by the honour guard at the wreath-laying ceremony. Such style, such grace. They looked almost like ballet dancers.” “They are ballet dancers! After those disgusting defections in America we have had to purge the entire Bolshoi Ballet. The stars are in the army now and the rest of them are doing their pirouettes in a salt mine in Siberia.”

“What a pity. We so much enjoyed their performances in Athens last summer. None of them defected there, you know.”

“I know. We found out from our subsequent interrogations that two members of the Bolshoi tried to defect in Athens but after waiting outside their hotel for two hours, trying to get hold of a taxi, they gave up in disgust and went back to bed.”

”Well, that’s one problem I don’t have to worry about.”

“What, finding a taxi?”

“No, defections. Actually, the opposite happens in my country. They come back from America, like one particular gentleman who came back at my invitation and who is making life difficult for me now.” “Can’t you pack him off to a bauxite mine or shut him up in an insane asylum?”

“Oh, no. I can’t do everything I like the way you can.”

“That’s funny. I was given to understand that nothing happens in Greece unless you personally order it to happen. Ah, well. The whole thing’s a joke, really. People think we have absolute and unlimited power. But we don’t really, do we? Talking of jokes have you heard the one they tell about me? “Which one?”

”The one about my aged mother visiting me from my home village for the first time. I show her over my luxurious apartments in the Kremlin, my lavishly-appointed dacha in the country and my collection of expensive cars. She is greatly impressed but then she takes me aside and whispers to me: “This is all very fine, Leonid, but aren’t you afraid the communists will come in and take it all away from you?” “No, I hadn’t heard it. It’s rather clever, actually.”

“Well, it’s not true at all. It wasn’t my mother who said, it, it was my Aunt Lara. Tell me, do they make jokes about you?”

“Yes, they do. But they’re mostly stupid jokes about my Serres accent.” “Well, I wouldn’t know, it’s all Greek to me! Tell me, what’s that gadget you’ve got there?”

“It’s a little comb for my eyebrows.” “Oh, fancy that. I could use one of those.”

“You like it? Take it. It’s yours.” “Oh, I couldn’t —” “No, really, I have another one in my sponge bag at the hotel.” “Oh, well. Thank you very much. I was really expecting another car for my collection. But this’ll do fine.” (The voices are interrupted here by the sound of flushing toilets.)

“Ready? Let’s go and tuck into the caviar and champagne now.”

The tape ended there.

The dark gentleman was looking at me anxiously. I held up a 100-drachma note and said: “I’m afraid this is just about what it’s worth.”

He looked disappointed. “I can’t get a square meal with that,” he protested. I held up two 100-drachma notes.

“That’s still not enough,” he said.

“You can get a square meal for 200 drachmas,” I pointed out.

“Not where I go. Don’t forget, I’m a member of the diplomatic corps and I have to keep up appearances!”

I held up a third 100-drachma note and said:

“That’s the limit. Take it or leave it.”

He took the money, tucked it under his loin cloth, picked up his shield and spear and bowed. “Thank you very much, sir. If you like, I can sell you all the other tapes we have. There’s no conversation on them, but perhaps you might like to use them for sound effects or something.”

“No thank you. This one is all I’m interested in. Good-bye now.”

“Good-bye. It’s been a pleasure doing business with you.”