With its rapidly-growing population, Athens has had to face many acute problems in recent years. One of these is a shortage of water. In an attempt to increase the water resources available to Athens, the Mornos Dam, located in Roumeli near Amfissa and Lidoriki, was started ten years ago. By late September water was reaching Athens from the lake growing behind the Mornos Dam two hundred and fifty kilometres away. One of the largest hydraulic projects in Europe, the artificial lake is to cover an area of 24,000 stremmata (6,000 acres) with a depth of hundreds of feet.

One aspect in the construction of this dam which has largely escaped notice in the many government pronouncements is the fate of Kallion, a village located near the dam site. Put succinctly, the village will be submerged beneath the newly-formed Mornos Lake and its residents forced to leave their homes. This is one of the few instances in Greece’s history where an inhabited community is to be abandoned as a result of a governmental decision unrelated to national defense needs. In place of natural attrition which usually serves as the death knell for many Greek villages, the necessity of an enforced leave-taking of patriarchal homes and fields has lent an aura of resignation to the remaining residents of Kallion as the dam waters steadily rise. It is obvious that Kallion was not always in these straits; its history belies its present state.

Once the site of a large city, Kallipolis, it flourished during the Roman period. From the archeological excavations presently being undertaken, it is clear that the strategic location of the site and the availability of good water have always been important factors in the history of Kallion. Yet, this archeological work is also doomed as the present extensive excavations are to be submerged, probably by the end of this year. A statue of Artemis and a remarkable mosaic floor were recently uncovered and sent to Delphi for examination and eventual display. The excavations were undertaken only recently although the site of Kallipolis was well-known to archeologists. The Mornos region has had a rich cultural and historical tradition for over two thousand years. In the now abandoned hamlet of Isovra near Kallion the great patriot Makriyannis was born in 1797. His famous memoirs, which have been recognized as a great prose classic only in the last fifty years, open with a description of his childhood in the Mornos valley.

The present village of Kallion and its inhabitants face their impending losses with equanimity along with a trace of gallows humour. Virtually cut off by poor roads and by the rising river which feeds the Mornos Lake, the village’s remaining fifty families will soon leave. Many will come to Athens to stay with sons and daughters. Tending flocks, cutting timber and farming were the traditional occupations in Kallion. In Athens, the displaced villagers, as one old woman poignantly said, “will move from chair to chair.” Life will be dramatically changed and television will replace kafeneion gossip and village chatter as time-fillers.

Yet, the destruction of the village was not a surprise. Initial surveys for the feasibility of the dam were begun in the 1960s and indicated that the village’s water source was an important element in the formation of the lake, along with the Mornos and Kokkinos rivers. In the early 1970s, compensation for homes, trees, and fields began. For the villagers who took the money from the government in the 1970s, the compensation was, according to the inhabitants of Kallion, “quite good”. Perversely, and in keeping with Greek tradition, much of the money was spent in buying apartments in Athens.

While the cash payment for the property was undoubtedly fair, the bitter notion remaining in the minds of the people of Kallion is that the diaspora could have been avoided. Many of the villagers wanted compensation in the form of land elsewhere in Greece so the village could remain as an entity. Several uninhabited sites were suggested but, apparently, the government preferred the relative ease of cash payment as a means of settlement. This topic of compensation is still discussed in the village today and its appeal is heightened as spiralling inflation continues and departure becomes imminent. In the light of the recent government policy about limiting the size of Athens and encouraging the growth of rural areas, the lack of compensation in the form of land seems difficult for the villagers to comprehend. Another serious problem confronts the villages in the area. This part of Roumeli is susceptible to earthquakes, and several serious tremors have occurred since the 1950s. Many people fear that the heavy weight of water created by the lake will cause the ground structure to shift and result in further earthquakes. This fear is keenly felt in the town of Lidoriki, county seat of the Eparchy of Doris, as well as in other surrounding areas. The anxiety has grown as the lake increases in size, and many inhabitants in the region are also making plans to move to Athens in the near future. A dearth of seismic information has increased this phobia and government officials seem indifferent and offer little hope to the villagers.

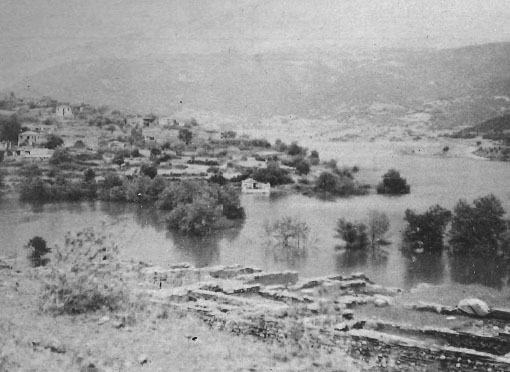

While the dam will undoubtedly produce some employment opportunities, a sound developmental project for the entire area is needed in order to stimulate a flagging economy and to keep more people from moving to Athens. Such a plan might consider the development of a national park. At the moment, however, the government’s plans seem to be focused on completing the technical details of the dam and then withdrawing, leaving the remaining villages to deal with their problems alone. Understandably, a visit to Kallion and its surrounding areas today shows many untended fields, unwatered trees, and unfinished repairs to houses and streets. The sound of bulldozers and trucks is omnipresent as they toil to finish their work. A glance shows that the water of the lake has already submerged the lower houses of the village and is rising at a fast rate. The talk overheard centers on the obvious: What shall we take when we leave? When will the last flocks be sold? The last tree cut? The general feeling is resignation to a fate only partially understood.

Perhaps the problem of the sacrifice of a village to the needs of a large metropolitan city was inevitable and will always remain as one of those difficult choices that governments and individuals must face. The choices which affect a relatively small number of people must be weighed with increased water supplies. However, the lack of a rational program concerning the development of the area, the method of repayment for lands and holdings which will soon be irretrievably lost, and the contradiction between announced governmental programs about demographics send confusing signals to the people of central Roumeli and especially to the villagers of Kallion. At the moment, many people there and in the surrounding areas feel that their well-being has been sacrificed to the needs of Athens and the expeditious handling of matters by government officials.