Their labour contributed directly to the successful Athenian resistance to the Persians in 480 B.C. and to the miracle of Periclean Athens that followed.

I first became interested in the silver mines of Lavrion from references I came across in history books. Although Xenophon wrote that they had been worked since “time immemorial” and poets described their discovery as a gift of the gods, little evidence has been found that mines existed in the area before 1,000 B.C. During the Early Iron Age the area was worked sporadically for lead and there are still some traces of these activities at the nearby site of Thorikos. However, it was not until the time of Solon, when the method of extracting silver from lead ore became generally known, that the first attempts were made to organize the mining of silver. The industry was intensified during the tyranny of Pisistratos, who himself had studied mining techniques on his family’s estates in Thrace. This may have led him to buy extensive lands in the area around Brauron and Lavrion. Even so, the activity remained commercially limited until the sudden discovery in 483 B.C. of an extraordinarily rich vein of silver under the second limestone crust at Lavrion. From then on it became the chief economic base for Athenian expansion.

At first it was proposed that the bonanza be paid off by granting ten drachmas each to every adult Athenian citizen. Themistocles, however, persuaded the Assembly of Athens to use a hundred talents of this silver to build a hundred triremes. Two years later the investment in naval development paid off at the Battle of Salamis in which the Greek Forces completely triumphed over the Persian navy. Thereafter the silver derived from the mining operations was incorporated into coinage (drachmas and tetradrachmas) particularly the famous “owls of Lavrion” which enabled Athens to furnish buildings for the Acropolis. The mines of Lavrion remained state-owned for centuries, although they were leased out to private entrepreneurs at a very low rate of interest.

The work, initially done by free citizens, became increasingly dependent on slaves as the demand grew. Conditions became so deplorable that during the Peloponnesian War some twenty thousand slaves revolted and entered the Spartan ranks. The mines flourished sporadically after the Peloponnesian War, being worked by the Macedonian kings and later by the Romans. According to Pausanias, work essentially ceased at the beginning of the Christian era.

In modern times, the mines have been reworked by Greek and French companies for lead, manganese and zinc. Much of the current mineral yield is not from new mine shafts but from reworking the ancient tailings.

My first attempts to discover the location of the mines afforded little information except that they were located near the present-day town of Lavrion, which lies some thirty miles east of Athens. Talking with some of the local people there, I was taken to a shack or two in the vicinity which contained numerous iridescent mineral specimens. Further questions only produced curious smiles. At most, the farmers would point vaguely to the west towards the Berzeko valley indicating the source of the finds. Intrigued, I began my search by following the first dirt track to the south. It was not long before my hopes were partially fulfilled, for I came upon hill after hill of tailings. Looking closer, I found small openings hidden here and there in the rocky hillside. With a light on my head and one in my right hand, I crept into the first shaft that was accessible. It was plain and simple, of no particular geometric configuration and rather roughly hewn. Since I was a neophyte I learned as I went along, trying to absorb any and all details from my dark and silent surroundings. There were no tracks on the floor —only a fine ashen dust which had fallen from the roof of the shaft over many years. My biggest problem was trying to determine whether this particular shaft was indeed an ancient one for there was nothing to guide me. While puzzling over the problem, I caught sight of a glitter of light from a small crack in the solid rock wall. On closer inspection I found an object which looked something like a wire, which I pried out with my knife. To my surprise it was a rusted nail of unknown age. Once again baffled, I proceeded, noting that the shaft was damper and warmer than the out-of-doors. I tediously studied the ceiling and the walls, looking for some markings which would indicate their age.

I soon came to a five-way intersection and decided to follow the most “ancient” looking tunnel. Just as I crossed its threshold, there lay above me an answer to part of the riddle. A bore-hole diagonally incised into the multicoloured strata proved that the shaft was a modern-day working. Somewhat dismayed, but hoping to learn more, I pushed into the hidden recess ahead of me. The somewhat dull brown lacklustre walls began to yield the more vibrant colours of greens, pinks and soft whites. I became progressively more enchanted by the variegated colours and forms located in numerous niches, crevices and cracks along the shaft wall. My pace picked up as a result, and I hurried forward in a bent-over position in eager anticipation of exquisite hexagonal quartz crystals, radiant azure schists and perhaps even that evanescent mineral —silver.

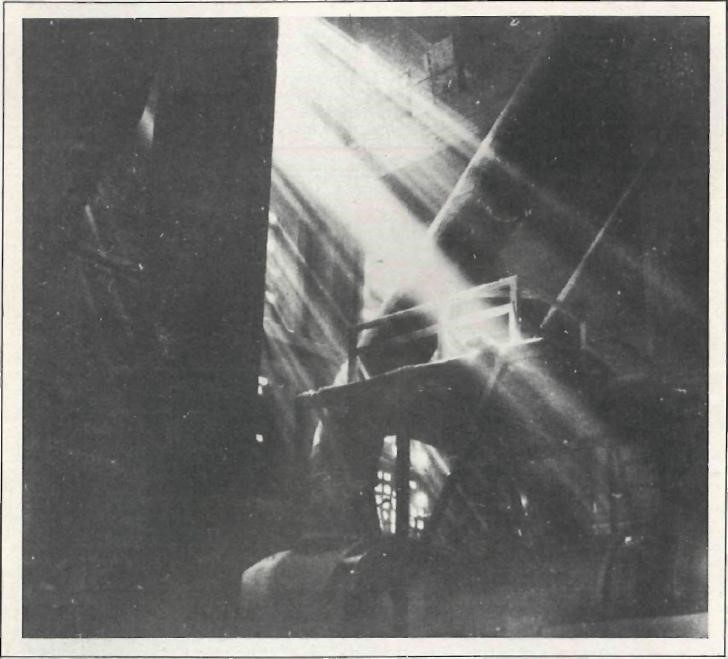

All of a sudden, however, the resplendence and designs vanished into a monotonous grey and there before me vertically transecting my shaft was another smaller one which came from above and passed into oblivion below. It was about one metre by one metre, perfectly square, and its walls contained thousands of small chip marks. I concluded that indeed this shaft was an ancient one. It was a masterpiece of careful workmanship and I was in awe to think I had stumbled upon it.

I was uneasy about exploring the shaft passing into the floor below me, but I noted that there were holes in one of its four walls. I used these holes as one uses stairs and so was able to descend rapidly and safely. To my delight it gave onto several other corridors and also a large gallery some twenty metres in height. It was incredible to look at this huge expanse supported by stone pillars deliberately carved for the purpose. There were numerous mineral specimens strewn here and there as well as pottery shards.

When I emerged some four hours later from what had seemed the dark bowels of the earth, I felt I had shared a oneness with time gone by. Far below me deep within the earth time had carefully preserved life which had ceased thousands of years ago. My trance was broken as a man in a tractor rattled past me on the stoney road.

I returned to these hallowed shafts over six times; each time seeing and learning something new. I concluded that many of the old mines had been reworked by modern methods and hands and, while the newer shafts had already rapidly aged, the old ones remained unchanged. With every visit I was left breathless by the picture of history frozen, as it were, underground.

Today if one visits this remarkable area of over two thousand mines one can almost hear the sound of a thousand hammers and chisels beating against the slate-grey walls. One has only to gaze over the vast hills of slag and rubble heaps to understand the adventure and toil that occurred here. Scattered here and there are cisterns and ore-washing areas used by the ancient miners. In addition, the location of smelteries and forges can be identified, as well as the foundations of living quarters, for these mines were cities complete with streets, wells, shops and dwellings where slaves worked most of their lives.

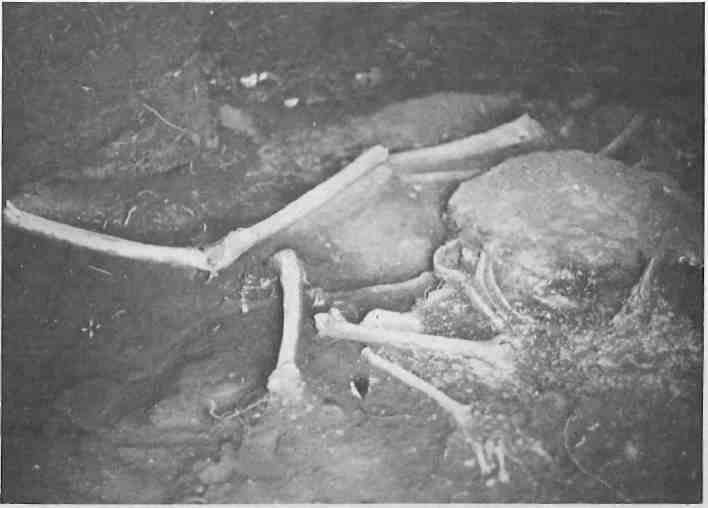

It is a curious experience to walk in crouched position the endless corridors of some of the shafts. The ancients cut them with perfection — each of the tunnels is large enough to admit a human body, though no more, and they are all chipped smooth. Occasionally you can find some artifact in situ; perhaps an oil lamp, amphora or spike.

Some of the shafts stop abruptly, perhaps denoting that the silver vein was exhausted; others go off at unusual angles, suggesting the pursuit of the rich metal. Still others end in a vertical shaft straight down for fifty to a hundred metres. Though breath-taking today, they were not meant to be so, for stair-holes and grips are conveniently built into the sides of the walls.

It is said that the Orphic cult was introduced into Athens through Thracian slaves who worked here. In this subterranean world it is easy to believe, as scholars have suggested, that the Myth of the Cave, immortalized by Plato to describe the human condition, originated in the slave-culture of the Lavrion mines because they rarely saw the light of day. Apart from the historical importance of these mines, the many beautiful and interesting mineral deposits remaining in the dark solitude of these shafts have a fascination of their own. One can only wonder how many people they have seen come and go.