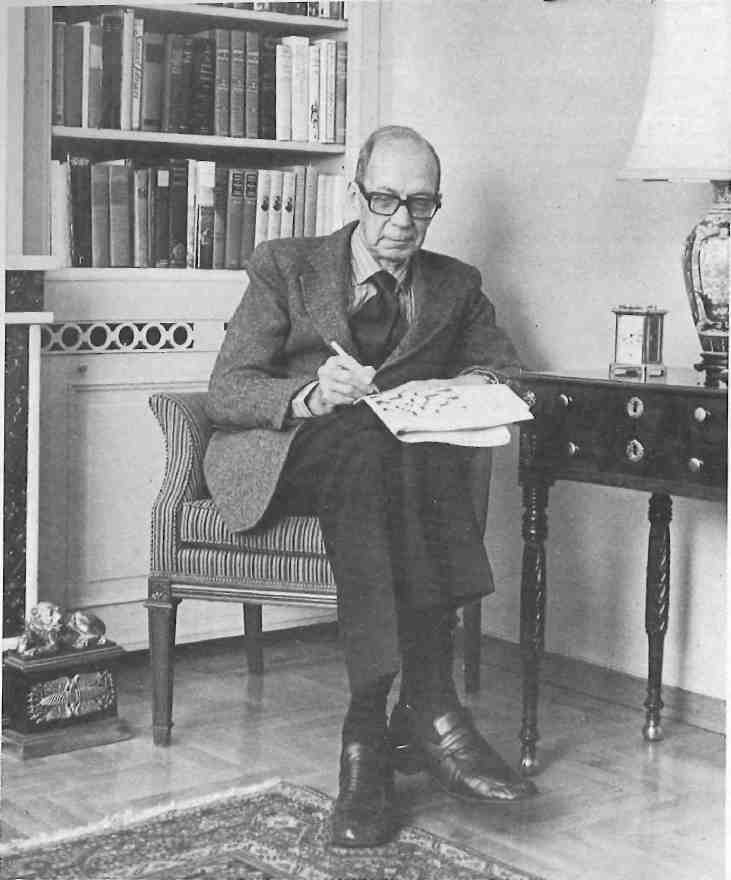

The handsome medal of gold and white enamel symbolizes the culmination of a life devoted to Greece: as a student of antiquity, as a professor, and finally as a librarian. In the splendid Gennadius Library in Athens, Francis Walton’s versatile talents have merged, and it is in this library that he intends to remain.

It is hard to imagine Dr. Walton retiring. Although he has been Director Emeritus since his official retirement in 1976, he still carries out a full range of activities at nearly the same pace that he has maintained since coming to the Library seventeen years ago. A tall, wiry man, his eyes dance with enthusiasm and cordiality as he describes with broad gestures the latest Gennadeion acquisition which may be a rare incunabulum (a book printed in the latter half of the 15th century) or the replacement of an item that the Library’s founder, John Gennadius, sold in a time of poverty in 1895.

The Gennadius Library bears the imprint of Walton’s active personality. Of the twenty-seven thousand books which have been acquired since the Library’s dedication in 1926, half were donated or purchased during his tenure. Dr. Walton’s guiding philosophy is in harmony with that of the founder, the great Greek bibliophile, John Gennadius. Gennadius’ own ambition when he started his book collection in the 1870s was, according to Walton, “to form a library that represented the creative genius of Greece at all periods, the influence of her arts and sciences upon the Western World, and the impression created by her natural beauty upon the traveller.” Likewise, it is Francis Walton’s specific goal for the Library that it contain within a Greek context as complete a collection as possible, in every given category of book. Such a sweeping goal could easily lead the undisciplined collector to make indiscriminate purchases. Indiscriminate, however, is the least appropriate adjective to characterize Walton’s selections. He is by nature and training an impeccable, cautious, and systematic scholar.

He was born in Philadelphia in 1910. At Haverford College he majored in Latin and Greek and received his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Classics from Harvard. While a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome, he first visited Greece in 1936 and fell under its spell. From that moment it was his dream that he might some day return to Greece. It was not until twenty years later, however, that an opportunity arose, when he received a Fulbright Research Grant for the academic years 1956-57 in Greece. By then he had a wife and two children. When he was offered a three-year appointment as Librarian of the Gennadius Library in 1960, he accepted with alacrity and the enthusiastic support of his family, resigning from his position as Chairman of the Department of Classics at Florida State University. In this sudden uprooting the family sold all of its possessions except for treasured books and some furniture.

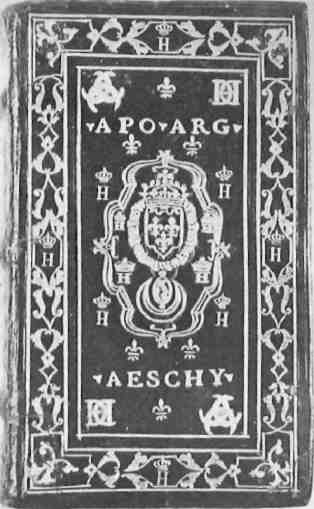

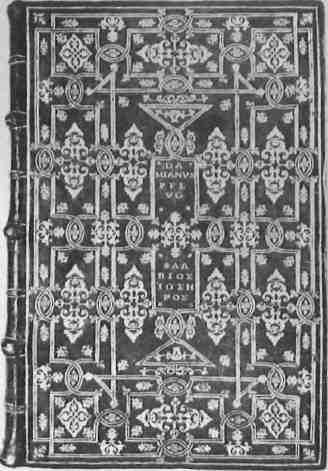

He freely admitted that he knew little or nothing about running a library, but traditionally the directors of the Gennadeion had been scholars in some field of Greek culture, rather than professional librarians. Miss Eurydice Demetracopoulou was a trained librarian and had been handling the more technical aspects of the Library for years. Walton’s first task, therefore, was to familiarize himself with the collection, which comprised books dating from 1470 to 1961, all of them in some way related to Greece and many of them, in magnificent bindings, which had belonged to kings, popes, cardinals and bibliophiles. When he assumed the directorship, the Library contained one of the richest collections on Greek subjects in the world.

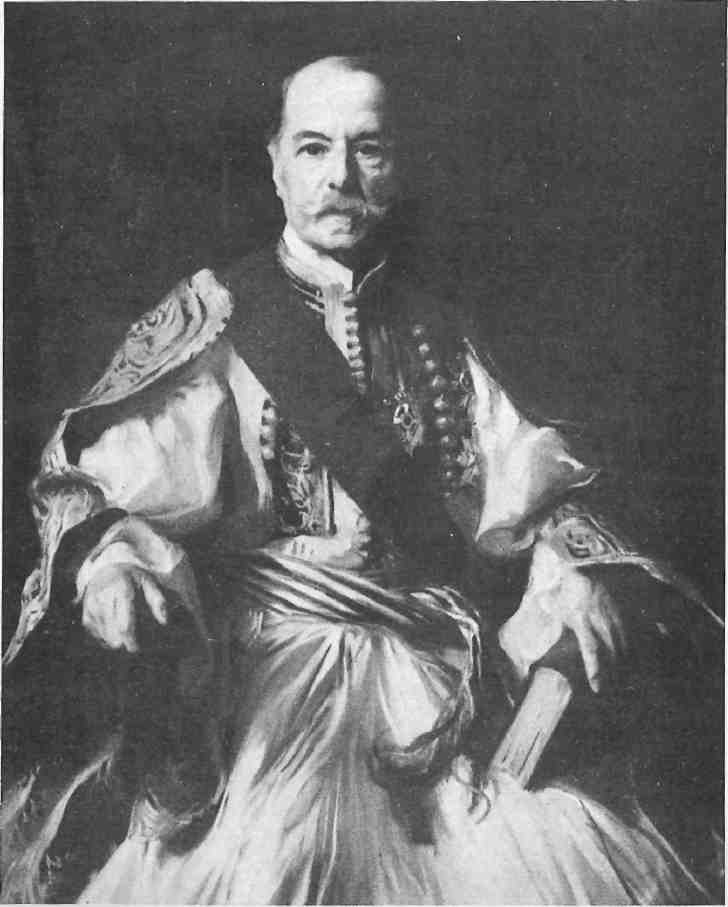

John Gennadius (1844-1937) had conceived of Greek civilization as a unity from antiquity to modern times. He realized that neither geographically nor culturally could Greece be limited by any definite boundaries, and thus his collection included works on the Balkans, Anatolia, Egypt, the Near East. He understood, too, the value of ephemeral materials and therefore gathered pamphlets and newspaper clippings on the early state of Modern Greece. He built a collection of particular strength in the early editions of classical, patristic and Byzantine authors. The religious section, to which he devoted special care, included the Greek Bible in editions beginning with the Psalterion (Milan, 1481) and the first printed edition of the New Testament (Basel, 1516). His valuable collection of Greek grammars is crowned by one of the most precious books in the Library, the Lascaris Grammar (Milan, 1476), the first Greek book with a given date. The total list of distinguished holdings would dazzle even the most knowledgeable bibliophile. Thus, the Library has a double distinction: it serves as an invaluable research library where Greece can be studied in its entirety and at the same time it holds a superb collection of valuable and rare books.

Gennadius, who first assembled these treasures, was one of Greece’s most brilliant diplomats. For over sixty years he served his country, principally in London. Walton has written of him:

Affable, energetic, and purposeful, he fully enjoyed the social and intellectual life of the English capital, and participated actively in both. Words came to him easily. As a speaker he was much in demand, and despite his official duties a steady stream of publications in English and Greek poured from his pen. Always Greece was the focus of his thought, and he was equally at home in any aspect of the subject: literary, historical, religious, or economic. With all this activity he still found time for the avocation that engaged his affections throughout and that will keep his memory fresh long after his other achievements are forgotten.

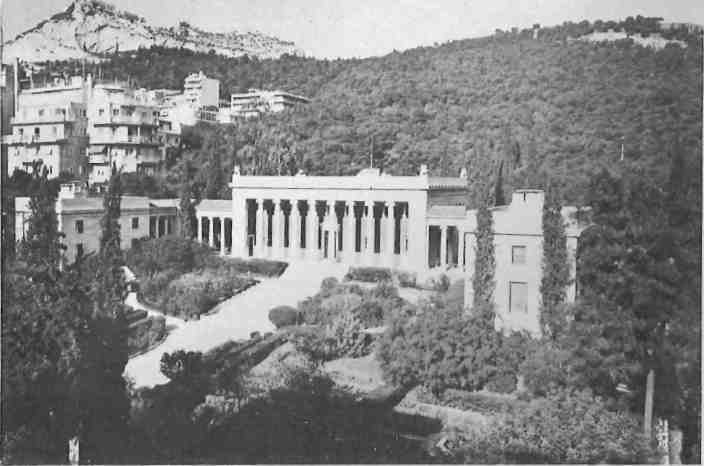

When Gennadius went to the United States in 1921 as Greece’s representative to the Naval Disarmament Conference on his last diplomatic mission, he made the decision to donate his magnificent collection of twenty-four thousand volumes to the American School of Classical Studies in Athens. The Greek Government gave the land opposite the American and British Schools on Souidias Street at the foot of Lycabettus. A grant from the Carnegie Corporation supplied the funds to construct a marble edifice. On their last journey to Greece in 1926, Gennadius and his English wife took part in the ceremony which marked the opening of the Gennadius Library, named by him in honour of his father who had been instrumental in the founding of Greece’s National Library.

In the gift of deed to the American School of Classical Studies in 1922, Gennadius stipulated that a catalogue of his collection be published. When Walton was appointed librarian, only the catalogue of the travel collection had been printed. He was urged to find some section to catalogue and publish.

During his year of absence (1963-64), when he went to Harvard as Visiting Professor of Classics full of enthusiasm for his new career as Librarian, Walton decided to publish the entire catalogue. During the first two years at the Library, he had studied the card catalogue, noting the many incomplete and unsightly entries. His assistant, Miss Demetracopoulou, warned him that the cards were in no condition to be published. “I was undaunted by her sound advice,” he admits today, and signed a contract with the publisher. Back in Athens and faced with the condition of the cards, he wrote to the publisher for a year of grace to tidy up and complete the cards. Finally in 1969 the Catalogue of the Gennadius Library appeared. It had taken not one but five years of frantic effort. Walton, Miss Demetracopoulou and two assistants made fifty-five thousand new cards, six thousand during the ten weeks when the publisher’s photographer was microfilming them. The catalogue, published in seven folio volumes, included 116,700 cards, photographically reproduced. In 1973 a first supplement volume appeared, which is available in most major libraries around the world, thus bringing the holdings of the Library to international attention.

Dr. Walton’s year at Harvard was also productive in other ways. When he first came to the Library, rare books lay outside his ken, but his contact with them during his first two years had whetted his interest. It was in Boston as a guest member of the Club of Old Volumes that he became acquainted with a lively and erudite group of bibliophiles. As a visitor, he was invited to give the first talk of the season. Fortunately, he had brought with him an ample selection of slides. His talk was favourably received and later in the course of the year he repeated “The Treasures of the Gennadius Library” before twenty different audiences up and down the eastern seaboard of the United States. Through his contact with the bibliophiles he was gradually developing an expertise in rare books and became excited by the possibility of expanding the precious collection of the Gennadeion. The limited budget, however, prevented such a project. Although the Library’s total number of books had been increased, through gifts, since its founding, its distinctive rare book collection had remained almost static.

By the end of his stay at Harvard, Walton had found a solution for some of his budgetary problems. He organized “The Friends of the Gennadius Library” and by 1965 he was able to publish an impressive list of charter members who had donated a total of $26,000. A new era had begun for the Gennadeion. The steadily increasing membership of “The Friends of the Gennadius Library” had enabled the Library for the first time to puchase rare books on a systematic basis. It was with the income from these donations that Francis Walton began his detective work of tracking down and replacing a portion of the books lost in the Gennadius sale in 1895.

The reasons for this sale hark back to 1892 when Greece suffered a financial crisis and had to recall three of her envoys in the West. Gennadius, who in 1890 had been promoted to the top post as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary at the Court of St. James’s, and accredited also to The Hague and Washington, was among those recalled. Gennadius had never been a wealthy man. When three years had passed without his being reappointed, he decided to liquidate his only capital — his books. Through Sotheby s, he sold a large portion, about three thousand items, of his remarkable collection.

The breadth of the auction was stunning. The sale catalogue, containing a long prefatory letter by Gennadius which notes in detail the outstanding features of the items, includes over sixty incunabula, one hundred and fifty-four lots of Byroniana, eighty New Testaments in Greek, Queen Elizabeth’s copy of Aesop’s Fables (1570), and a host of other rare and unique items. The catalogue from Sotheby’s which Gennadius fashioned for himself is interleaved and annotated. It scrupulously documents the sale data, listing not only the purchaser, the price for each lot from the Sotheby sale, but also the date, price, and source of the original purchase made by him. Moreover, in red ink Gennadius noted in the catalogue subsequent repurchases he made at later dates when his financial circumstances had improved. It is this, Gennadius’ own personal, catalogue, that Dr. Walton keeps within arm’s reach of his desk in his office.

How does Walton track down lost items from the 1895 sale? He scans all of the current sale catalogues; When he spots a lost title he purchases it. So far he has acquired about three hundred replacement copies. Of these only ten are the very copies owned formerly by Gennadius. How does Walton know which were actually held by the great Greek bibliophile? Gennadius had written in red ink on the fly leaf of each book the catalogue number of the Sotheby sale. When Walton orders a book he has no way of determining whether it is a Gennadius edition. He says that it is a great thrill to open the book cover and find the notation in red ink written by Gennadius’ hand.

Dr. Walton makes it clear that he selects replacements of the books which were sold at the Sotheby auction only if they are relevant to the present-day collection. He is not sentimental about passing up a purchase if it is not absolutely germane.

The purchasing of rare items is not restricted to the lost collection of 1895. The Library during Walton’s tenure has become a great repository for notable archives. Other categories such as early Greek grammars, travel books dating from the sixteenth century, documents, autograph letters and manuscripts of historical worth have been given special emphasis by Walton. In 1962 the Library acquired the main body of Heinrich Schliemann’s papers. Some time later, it was able to add the papers from his Athenian period (1870-1890) when he excavated Troy and Mycenae. It was from the Gennadeion’s Schliemann Archives that Irving Stone wrote his best-seller, The Greek Treasure. A great source of pride to the Gennadeion is the George Seferis Archives which Greece’s only Nobel Prize Laureate willed to the Library. His diplomatic and literary papers, catalogued by Theofilis Frangopoulos, are available to scholars. Professor John Rexine will use the Seferis Papers this autumn to write the poet’s biography. In addition, the purchase of the archives of diplomat Constantine Mousouros which cover the years 1836-1874, has provided a rare historical source for research on the Crimean War and the reign of King Otto.

One of the most important events to occur during Walton’s tenure was the construction of the two new wings added to the original structure. The Trustees of the American School of Classical Studies decided in 1970 to build two extensions in the form of L-shaped wings to provide space for the Helen Stathatos Macedonian Room, an exhibition hall, new offices and five stories of book stacks. Every care was taken by the architect, Paul Mylonas, to preserve the original symmetry of the building. The reopening was commemorated with an exhibition by the famous Greek artist Nikos Hadjikyriakos Ghikas, who donated some of the works on display.

Among Dr. Walton’s significant activities at the Gennadeion have been his numerous publications. Among them is The Griffon, named for the four stone creatures which adorn the upper corners of the building. Appearing first in 1965, it is the medium through which he keeps “The Friends of the Gennadius Library” informed. It is written in a delightful but erudite style which reflects his humour, scholarship and deep involvement with the Library. Intended as an annual publication, it has, however, not always appeared with scheduled regularity. Walton now refers to it wryly as “an occasional publication”.

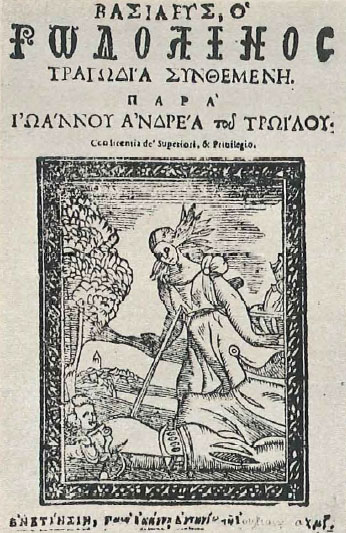

A promising innovation at the Library is the publication of books. The new project was inaugurated in 1976 with a facsimile of a book owned by the Gennadeion, Basileus, Ο Rodolinos.

Since this tragedy in verse printed in Venice in 1647 had never been reprinted and survived only in this copy, the publication and distribution of facsimiles make this gem of the Cretan Renaissance available to the interested reading audience. The contribution was made possible by a fund established in memory of Eurydice Demetracopoulou whose devotion to the library was life-long. Another reprint from the Gennadeion Treasures is scheduled to appear late this year.

It is not only through publications and the giving of lectures, but” also through the lending of the Gennadeion possessions to worthy international exhibitions that Walton gives the Library wide exposure. The gathering of bibliophiles from all over the world in the autumn of 1977 at the Tenth International Bibliophile Congress was held in Athens. Two sessions were held at the Library where Dr. Walton had arranged displays of some of the rare and unique items.

The Gennadeion is open to the public. The Greek words carved into the marble frieze over the Library’s entrance tell much about its spirit. Translated into English, they read: “Whoever studies Greek culture is called Greek.”