“What does our entry into the Common Market mean?”

So from then on, without being too direct or abrupt with anyone I chanced to meet, I gently steered the conversation towards the subject of the Common Market and waited, all ears, to hear what they had to say.

My first encounter was with an aristocratic lady who lives in Kolonaki and can trace her ancestry as far back as the sixth century in Byzantium. She once confided to me that she was a direct descendant of Narses, a famous court official and general in Justinian’s time. I later discovered that Narses had been a eunuch but decided not to press the point with her.

She had invited me to dinner and, as I was the first to arrive, I found the occasion to ask her what she knew about the Common Market.

“Oh,” she said, “we have one here in Kolonaki. Every Friday I think it is, on Xenocratous Street. My maid does the weekly shopping there and I must say it’s much cheaper than the shops.”

“No, no,” I said. “I don’t mean the laiki agora. I’m asking you about the koini agora, the Common Market.”

“If it’s common, I certainly will not have anything to do with it. Mind you, I’m not a snob. But there’s so much vulgarity around these days that people like me have a responsibility and an obligation to …”

We were interrupted by the arrival of another guest — a retired diplomat I had known for a long time. He was getting on in years but I knew he still took an active interest in public affairs and was about to publish his memoirs.

I steered him to a corner of the room, sat him down with a glass of whiskey in his hand and a bowl of salted peanuts by his side, and, after a few minutes of small talk, I popped the question.

“What do you think of our entry into the Common Market?”

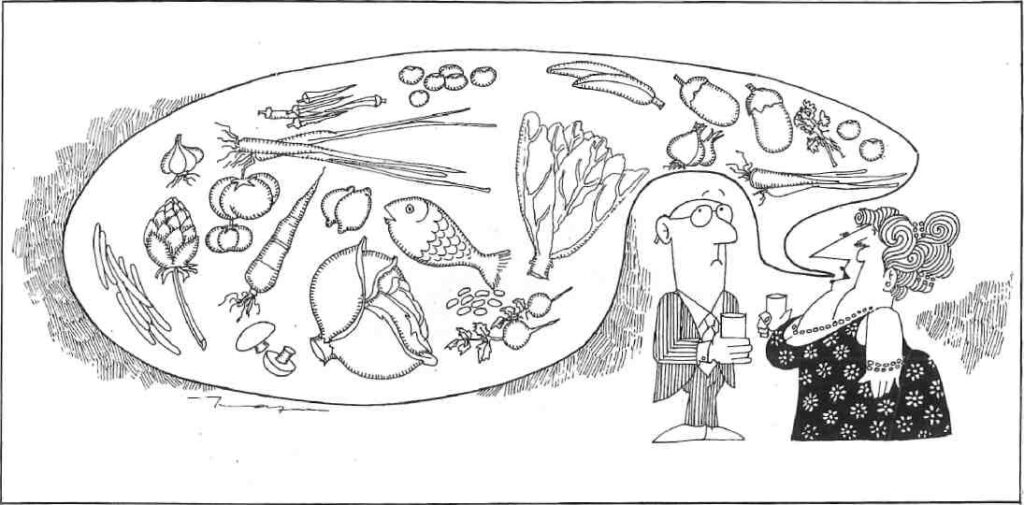

He looked at me through his thick-lensed glasses, took a sip of whiskey, stuffed his mouth with a handful of peanuts and then stared beyond me, as if in thought. I waited expectantly for the pearls of wisdom that were being formed in his mind. After a little while I got impatient and I was just about to ask my question again when he said: “Look at that painting over there. Isn’t it a little crooked? I can’t stand crooked paintings.” I looked at the painting on the opposite wall. It was indeed slightly crooked. I went over and straightened it. Then I came back and drew my chair closer to him so he could not see beyond my face. I said: “You haven’t told me what you think of our entry into the EEC. Can you tell me what it means?”

He looked at me with a slightly pained expression on his face. Then my question registered and he drew closer to me with a conspiratorial air. “You know,” he said, “it’s funny that you should ask me that. I’ve just completed a chapter in my memoirs about the importance of that splendid organization during the war and how vital messages were sent to underground organisations in occupied Europe, including Greece. I specifically mention, in my memoirs, one occasion when…”

“Wait a minute, wait a minute,” I interrupted. “What has the EEC got to do with the war, for heaven’s sake!”

“EEC? Oh, I thought you said BBC. I’m sorry.”

By this time, we were being ushered into the dining room and as he was not seated in my immediate vicinity, I couldn’t pin him down again. I turned to the lady who was seated on my right. She had been introduced to me as the wife of a Greek official on the international staff of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in Brussels, on a short holiday in Athens,

During the course of my conversation with her I discovered she had two grown children who no longer needed her full attention and that, in order to keep herself occupied she had been working for the past year in none other than the EEC administrative offices in the Belgian capital.

I was so delighted to hear this I almost kissed her. I said: “You can’t imagine how overjoyed I am at meeting you. At last I have met someone who can tell me what the Common Market is all about. What Greece’s entry will mean to us and what we can expect from it. Madame, I am all ears. Please enlighten this benighted soul who sits beside you, toying with his roast veal and mashed potatoes, plunged in a slough of despond because a month ago, in this great, polluted city, a historic document was signed about which he can make neither head nor tail.”

She laughed gaily and took a sip of wine. “You are very amusing,” she said, looking at me coyly.

“I am also very ignorant,” I replied.

“But didn’t you hear the speeches at the signing ceremony? Didn’t you listen to the commentators on television? Didn’t you read the articles in the newspapers? What more could I tell you?” she said.

“Madame, I have been subjected to so much of all that that I had to resort to medical treatment to cure myself of it. You may be in a better position to interpret all that verbiage, since you are intimately connected with the EEC administration. But I can assure you that ordinary mortals, with an average intelligence and an average interest in public affairs were left with a thoroughly confused melange of peaches, olive oil, tomato paste, price supports, subsidies, assistance to the tune of several millions of dollars, a European parliament that has no powers, migrant workers who are not allowed to migrate and more peaches swimming in olive oil and tomato paste and…” The lady had grown pale.

“I think I’m going to be sick,” she said.

“I know exactly how you feel,” I said. “Koinagoretic dyspepsia. I’ve got just the thing for you.”

I poured out a glass of water for her and dropped an Alka Seltzer into it. She drank it and then went to lie down in the hostess’s bedroom.

Dinner was over and I looked around for the retired diplomat. He was back in his corner with another glass of whiskey in his hand and looking very pleased with himself. I started toward him, then changed my mind. I tilted the painting on the opposite wall to a forty-five degree angle, thanked my hostess for a wonderful evening and went home.