If this is true, Greece should have no worries about being in the front rank of civilized countries because, as you may remember reading in the March issue of this magazine, none other than the World Health Organisation has rated Athens as the noisiest city in the world.

But the WHO survey makes no mention of what causes us Greeks to be so noisy. An interesting theory in this respect is held by Professor Panayotis Kefalosystolakis, an authority on manic manifestations and a consultant at several mental institutions.

I visited the Professor in his consulting rooms and he came to the point immediately.

“When did it first start?” he asked.

“When did what first start? “I asked, in turn.

“Whatever is troubling you,” he said.

“Nothing is troubling me!” I exclaimed.

He looked at me with a quizzical expression on his face, as if to say ‘that’s what you think, but I know better.’

“Look,” I explained, “I’m not a loony. All I want is your opinion on why Greeks are such noisy people. It’s as simple as that.”

The Professor sighed, looked at me pityingly and said, “All right. I’ll go along with you for the moment. You want to know why we like making a lot of noise, is that it?”

“That’s it,” I nodded emphatically.

He removed his glasses and gazed out of the window for a moment, collecting his thoughts. Then he put his glasses on again and said, “We Greeks have a tendency to blame most of our faults on the four centuries of Turkish occupation, sometimes wrongly but sometimes with good cause. In this case, I would definitely say that the Turkish occupation was indeed a primary cause.”

“How come?” I asked.

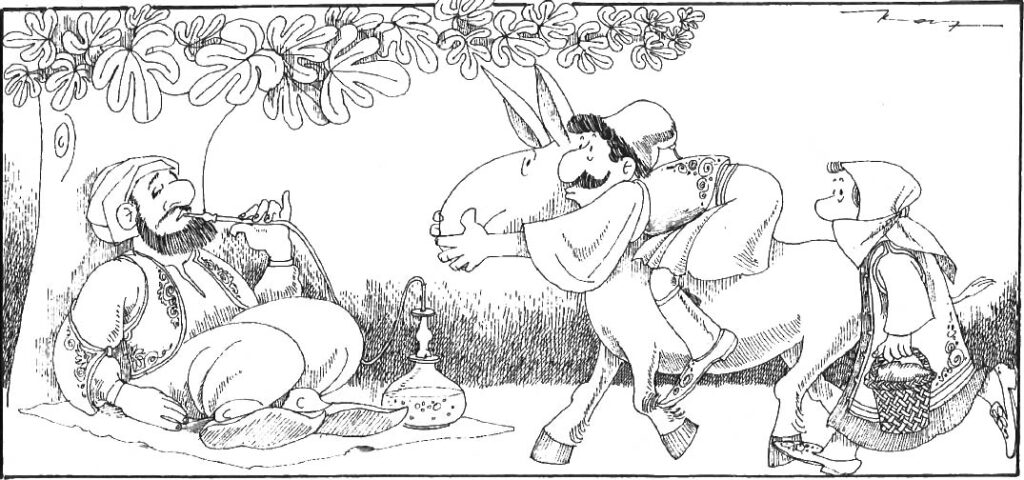

“It’s like this. As you know, the Turks are a very silent and taciturn people. After they conquered Greece they would spend most of their time sitting on a divan under a shady tree in their front gardens, smoking a water-pipe and looking very wise. They never said anything and they never did any work. They didn’t even collect the taxes. They got somebody else to do that for them.

“And so we poor Greeks had to go about our various occupations as silently as possible so as not to disturb these wise-looking Turks who, I might add, were quite capable of chopping off our heads with a silent swipe of their scimitars if we as much as cleared our throats in their presence.

“This went on for four hundred years until one day, a Greek plucked up the courage to ask a Turk what he was thinking of, sitting there on his ottoman and looking wise.”

The Turk nearly swallowed the amber mouthpiece of his hubbly-bubbly in surprise and said, ‘What am I thinking of? Nothing, of course. Why should I have to think of anything?’

“The Greek dashed off immediately and spread the word to all his fellow countrymen. The Turks were not sitting and thinking. They were just sitting. The signal was given for a very violent and very noisy uprising and before long, the Turk was driven out of the country. It was such a nerve-shattering experience for him that from that time onwards he became the sick man of Europe.

“The Greeks were then free to make as much noise as possible and this they have been doing ever since.”

At this point the Professor stopped to give me time to finish taking down what he was saying in my notebook. When I had done so, I stopped writing and looked at him expectantly, waiting for him to continue.

“Why are you chewing the top of your pencil?” he asked me.

I pulled the top of the pencil out of my mouth quickly and made a deprecatory gesture. “Nervous habit, I guess. Forgive me.”

He jotted something on the pad in front of him and I made out the words: ‘Compulsive xylophagomania.’ “Well, to go on. As I said, the love for noise was a direct and natural reaction to four centuries of enforced silence and we are still getting it out of our systems in various ways. By conducting ordinary conversations so loudly that foreigners often think we are quarreling. By banging desk tops in parliament to show our disapproval of a speaker’s arguments. By doctoring the exhausts of our motorcycles so we can career majestically down the street with the ear-splitting din of an unmuffled two-stroke engine. By honking impatiently at the car in front of us a split second after the light turns green. By ripping up roads at the slightest excuse so we can revel in the staccato jangle of pneumatic drills. By placing our international airport in the heart of a residential area so the inhabitants can enjoy the sublime thunder of jet engines.”

The Professor stopped again and asked me why I was jiggling my knee up and down. I stopped jiggling it and said, in embarrassment: “Another nervous habit, I suppose.”

I watched him note: ‘Compulsive gonatospasmic mania’.

“To goon: By fitting our dance halls, discotheques and bouzoukia joints with powerful amplifiers and playing them at full volume as we do with our television sets and with the radio sets in our homes and in our cars.”

The Professor stopped again and I wondered what I was doing that he would note this time on that ominous pad on his desk. He didn’t say anything and I grinned at him in nervous relief, whereupon he jotted down: ‘Nervous grinning.’

I “decided to disregard his rather annoying professional interest in me and asked:

“When will it all end? When will we have played out this reaction to the four hundred years of silence and become normal again?”

He took his glasses off and gazed out of the window again. Then he put them on and said:

“I really don’t know. You see, it’s something of a vicious circle. Today we’re surrounded by so much vocal, mechanical and electronic noise that we are all slowly going deaf. So eventually we shall have to talk loudly and play our music at full volume because we won’t be able to hear it otherwise.”

“A rather depressing outlook,” I ventured.

The Professor shrugged. “There are other things that are more serious,” he said.

“Such as?” I inquired.

“Such as compulsive xylophagomania, gonatospasmic mania and nervous grinning,” he said, looking at me meaningly.

I gathered up my pencil and, my notebook, drew myself to my full height and stalked to the door. As I opened it, I looked back at the Professor and said pointedly: “If you think my little nervous habits are serious, what about yours? Why do you take your glasses off and look out of the window every time you try to collect your thoughts?”

As I closed the door quickly behind me, I caught a final glimpse of the Professor staring at my disappearing figure with a very shattered-looking expression on his face.