From the seventeenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, the highlight of visits by adventuresome European travellers to the Cycladic islands was an expedition into the cave of Antiparos. Up until forty years ago, a descent into the dark cavern was made with ropes and ladders. Today, the expedition is no longer dangerous and several times daily during the summer months thousands of casually dressed tourists travel by motor-boat from the nearby island of Paros to the tiny Antiparos.

Donkeys and mules carry the visitors to the mouth of the cave, located near the summit of Mount Agios Yannis, one hundred and eighty metres above sea-level. Four hundred and twelve cement steps and electricity have eased the modern adventurer’s journey to the bottom of the cave. The first two hundred and thirty steps lead to a huge “hall” known as the cathedral, another forty-three to a platform and an “altar”, and the last one hundred and thirty-six to the bottom of the cave.

Joined in prehistoric times to neighbouring Paros, Antiparos is today a separate island with a population of less than one thousand. Its major claim to fame is the cave which earns this otherwise insignificant island a short entry in most reference books. In 1780, C.S. Sonnini, a French naval officer on assignment in Greece for Louis XVI, wrote: “What renders Antiparos one of the most famous islands of the Archipelago and even the world is the grotto which penetrates into the bosom to a great depth and communicates beneath the waters with some neighbouring islands, an abyss whose windings have not yet been discovered.” In 1802, the famous British mineralogist, Edward David Clarke, called the cave “the greatest natural curiosity of its kind in the known world, surpassing in beauty the caverns at Salernum and Terni”.

The numerous graffiti throughout the cave testify to the many visitors over the centuries. Among the luminaries who risked the descent into this renowned natural phenomenon were, in 1783, John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich, after whom the Sandwich Islands and the sandwich itself were named; in 1767, Baron Friedrich von Riedesel, a German army officer who commanded the British Brunswick contingent during the American Revolution; in 1808, William Martin Leake, the British antiquarian and classical topographer. Otto I, the first king of Greece, and Queen Amalia called at Antiparos in 1840. Although two sturdy Pariotes were ceremoniously assigned the task of assisting the sovereign, he shunned their attempts to prop him up during the descent, and having persuaded his overzealous subjects that kings in Europe were allowed “to exercise their own limbs” made it without help to the bottom of the cave where he scratched his name onto a rock. Queen Amalia waited at the entrance where, it is recorded, she lost a diamond bracelet. (It was discovered two years later by an islander who returned it to the Queen and was given a reward of ten thousand drachmas.) Queen Olga was more adventurous. In 1876, she ventured down into the cave, descending by ladder with her husband, King George I. The French natural scientist, Joseph Pitten de Tournefort, wrote a vivid account of his visit late in the seventeenth century.

You go forward to the bottom of the cavern by a great descent of about twenty paces long, this is the passage into the grotto, and this passage is only a very dark hole, in which you cannot walk upright, not without the help of torches. First you go down a frightful precipice by means of a rope, which you take care to fasten at the entrance. From the bottom of this precipice you slide down into another much more terrible, the sides very slippery, and deep abysses on the left hand, they place a ladder aside of the abysses, and by its means we tremblingly got down a rock that was perfectly perpendicular. We continued to make our way through places somewhat less dangerous, but when we thought ourselves to be on sure ground, the most frightful leap of all stopped us short, and we had infallibly broken our necks, had we not had notice, and been kept back by our guides… To get down here, we were forced to slide on our backs along a great rock, and without the assistance of another rope, we had fallen down into horrible quagmires. When we came to the bottom of the ladder, we again rolled over rocks, sometimes on our bellies, according as we found most ease, and after all these fatigues, we at length entered that admirable grotto…

The perilous deep “abysses” scattered throughout the cavern, a source of fear to all those who penetrated into the cave, gave rise to colourful folklore. James Theodore Bent, the British jurist and philosopher, was told by the islanders when he visited Antiparos in the nineteenth century that a goat, placed in one of the holes, reappeared two hours later at a small church dedicated to Saint Michael. Shepherds who occasionally slept at the entrance to the cave told of strange noises rising out of the cavern. Since the cave was believed by many islanders to be the entrance to Hades, they were, not surprisingly, terrified by the sounds.

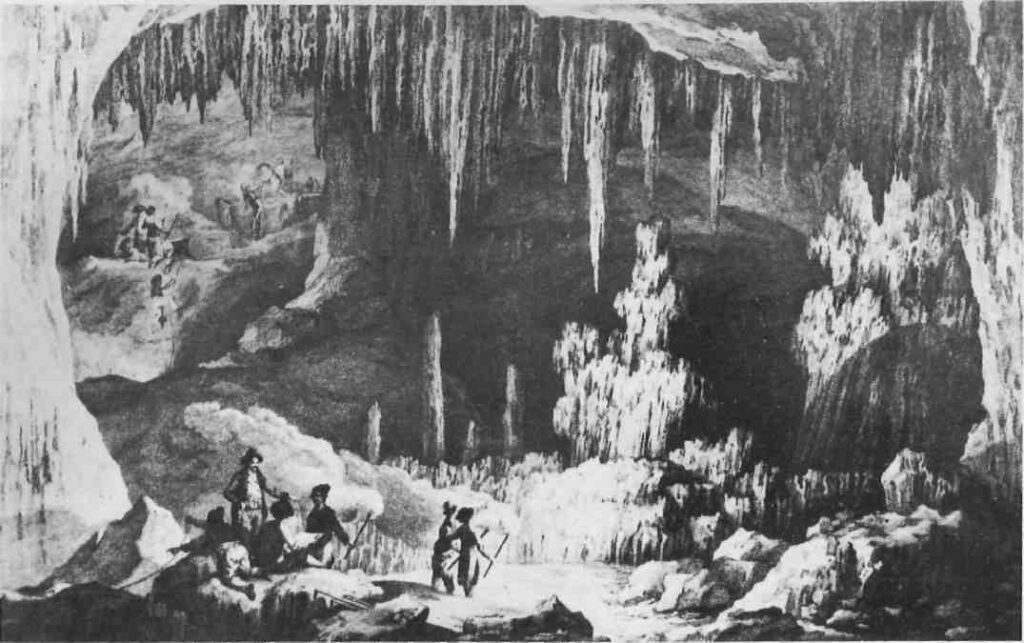

Despite such superstitions, many European visitors were struck by the religious images evoked by the interior formations of the cavern. The imposing “hall” with its stalagmites sparkling like gems, reminded some of a Gothic cathedral, its “dome” seeming to be supported by elegant “pillars”. The stalactites, hanging from the roof at one end of the “cathedral”, reminded others of an immense pipe organ, while the stalagmites, rising from the floor of the cave, seemed to take on the shapes of saints.

Visitors to the cave, intrigued by the splendour of the stalagmites and stalactites, would often break off pieces as souvenirs, which in time made their way to museums and other institutions abroad. The Marquis de Nointel, when making arrangements for his descent, included in his entourage two skilled draughtsmen and four masons with tools to loosen and lift away the more cumbersome pieces. He carried his collection to Paris where it was presented to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Medals. Mineralogist Edward Daniel Clarke visited the cave in 1802, and returned to England with a valuable selection. He wrote: “We had the great fortune to bring many of these specimens to England and to the University of Cambridge, where they have been annually exhibited during the Mineralogical Lectures.”

Some thirty years earlier, during the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-74, a Russian fleet of almost thirty ships anchored at Paros. A Russian contingent visited the cave and collected some particularly fine specimens for a museum in St. Petersburg. Each generation of visitors has thus claimed its share of these outstanding natural treasures. The last major destruction occurred during the Second World War when Greek and British commandos used the cave as a hiding place. In 1942, hand grenades thrown into the cave by Italian soldiers destroyed many of the natural formations.

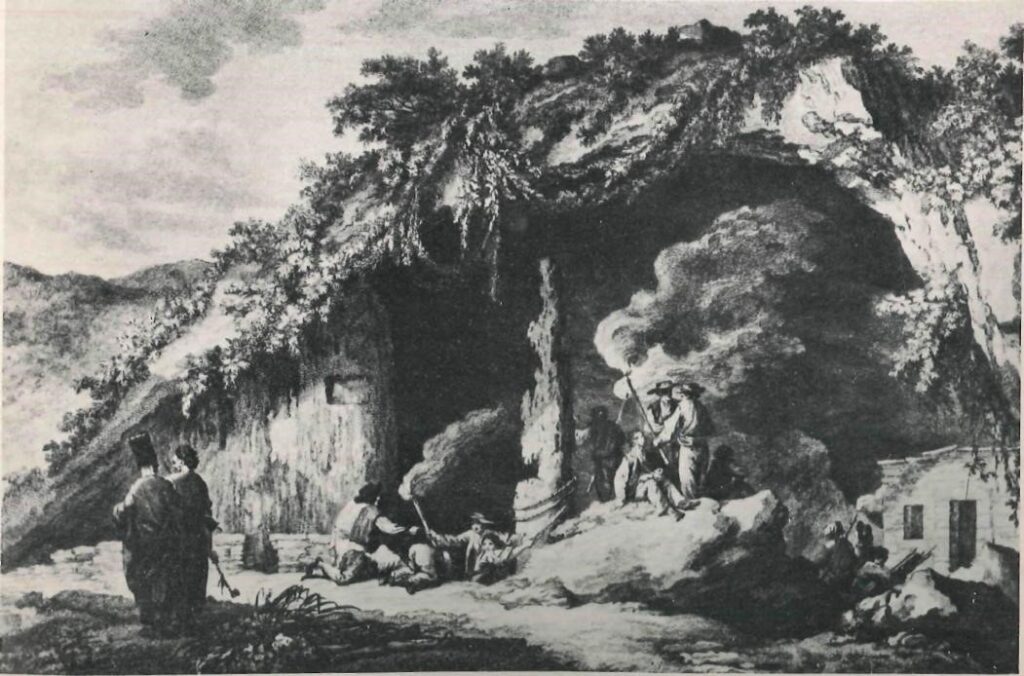

The most unusual visit to the cave was certainly that of the Marquis de Nointel who arrived in Paros on the evening of December 16, 1673. Paros was then under Turkish rule. As befitted the French Ambassador to the Sublime Porte in Constantinople, the Marquis was welcomed by the civic and religious leaders of the island while four pirate ships anchored in the harbour honoured him with salvoes. The Ambassador, being an adventurer and having no doubt heard of the spiritual associations connected with the cavern on Antiparos, decided to make the descent on Chrismas Eve. Accompanied by a colourful entourage of more than five hundred — including his Capuchin chaplains and domestic staff as well as assorted corsairs, merchants, and curious islanders — and equipped with numerous torches, candles, and ropes, the Ambassador set off for Antiparos. There the group was provided with mules and donkeys and escorted to the entrance of the cave, where they no doubt paused to admire the scenic view of the Aegean, with the islands of Ios, Sikinos, and Folegandros visible in the distance, before venturing into the cavern.

The first of several heavy ropes to be used in the descent was fastened to a huge stalagmite which stood like a sentry at the mouth of the cave. Before beginning the climb, the group undoubtedly observed the local custom of firing off their guns to drive away the ghosts and hobgoblins believed to inhabit the entrance to the unknown. It was several hours before the Marquis and his entourage reached the area where they could conduct their Christmas service. The humidity, the precipitous rocks, the slippery ropes, as well as the heavy smoke from the huge torches must have made the descent uncomfortable as well as hazardous. Yet, once they reached the great hall, which was to serve as their “cathedral”, fear and discomfort were transformed into amazement.

Beautiful specimens of stalagmites and stalactites filled an enormous area spanning a length of forty-five metres, a width of thirty metres, and a height of twenty-five. So overwhelmed was the Ambassador by the beauty and grandeur of the site that he decided to spend all three days of Christmas in the cave. An “altar” was located — a stalagmite much like a pyramid in appearance. Not only was its base suitable for the eucharistictable, it was even properly oriented. Here the eucharist was celebrated at midnight on the twenty-fourth of December. Men posted in every precipice along the route from the “altar” to the entrance of the cave, gave the signal with their handkerchiefs at the moment of the elevation of the host. Twenty-four cannons at the entrance of the cavern were fired. The festive high mass was accompanied by the music of numerous trumpets, woodwinds, and stringed instruments. Immediately after the service an inscription in Latin was carefully scratched into the base of the stalagmite which formed the altar, where it can still be seen:

HIC IPSE CHRISTUS ADFUIT EJUS NATALI DIE MEDIA NOCTE CELEBRATO MDCLXXIII.

“Here was Christ Himself at midnight when His Nativity was celebrated in 1673.”

Sleeping quarters for the Ambassador were established near the altar, in a small “chamber” about three metres long and three metres wide. The other members of the group were scattered throughout the cave. Providing sufficient food and water for this vast company of people was, of course, a major problem. His Excellency’s chaplains are said to have located a spring of fresh water in the cave, but there is no record of how food was provided. Day and night, for three days, with one hundred large, wax torches, and four hundred oil lamps illuminating the cavern, the Marquis and his entourage kept their Christmas vigil.