Far below the massive and stoney mountain crags, a tranquil plain unfolds gently into the Aegean. The melancholy cypress and the neglected olive trees seem to sigh with memories of ancient battles, the immense, stark mound of the tomb of the Athenians mutely reminding one that here in the autumn of 490 B.C. a Greek contingent led by Miltiades defeated the numerically superior Persian force.

There are many legends associated with the Battle of Marathon. From Herodotus, who lived during the same era, we learn of Phidippides, the courier dispatched by the Athenians to Sparta to seek aid after the landing of the Persians. He is said to have run one hundred and fifty miles in two days. The legend which added the word “marathon” to our language and established the criteria for today’s marathon race, however, involved another messenger, identified by Plutarch in the second century A.D. as Eucles. He is said to have run from Marathon to Athens without stopping to announce the Athenian’s victory over the Persians — after which he collapsed and died from exhaustion.

Over the centuries, the two versions meshed and contemporary legend usually associates Phidippides with the victory run to Athens. Thus, the organizers of the first modern Olympiad held in Athens in 1896 established the marathon race to commemorate the feat attributed by tradition to Phidippides. (Appropriately, that first marathon race was won by a Greek, Spyridon Loues.) Since then, the marathon has been an integral part of all major international track events. Long distance races had no place in the athletics of ancient Greece, the majority of track events at Olympia being less than three miles. The length of the first marathon in 1896 was set at twenty-four miles, the distance from Athens to Marathon. In subsequent Olympiads, it was extended to twenty-six miles, three hundred and eighty-five yards.

Over fifteen hundred participants gathered in Marathon on the ninth of October for the biannual “Classic Greek Marathon”. The event, which is to runners what performing at Bayreuth or La Scala is to opera singers, drew people from all the world with particularly large contingents from Germany, the Scandinavian countries, Japan, and China. I had decided to participate last spring, to determine the physical effects of such a test of endurance and to duplicate as closely as possible the conditions of the first legendary run.

Presumably, the runner of the original marathon had not trained for his ordeal and in all likelihood he had run barefoot. I thus trained intermittently for one month, running no more than a total of seventy miles. Two or three times a week I allowed myself a run of two miles and once a week a run of fifteen miles—barefoot. My reasoning was that the running shoe is a contemporary device never used by our ancestors and the human foot had not undergone sufficient evolutionary change to necessitate the support of such footwear. One of the major difficulties I anticipated was the soles of my feet. After the initial blisters disappeared, they presented no problem. In fact, they eventually became smoother and softer from prolonged contact with the ground, which had an effect similar to massaging ,with a pumice stone. Another source of discomfort was a painful ligament on the outside of my right leg, the causes of which were baffling. My own diagnosis was that it was the result of a shift in body weight when not wearing shoes, a theory later supported by a well-known Athenian orthopaedic surgeon.

Five days before the race I cut back on my intake of food, restricting myself to grapes, nuts and other edibles that would most closely approximate the diet of a runner in ancient times. I began to plan the details of my run. Although the ancient course stretched out along an uneven terrain of hills and valleys, I would have to follow the route of the modern paved road. I decided to wear only shorts, since runners in ancient times often ran in the nude, and I planned to drink no water. Since there are few natural springs along the way, I imagined that the first runner was not likely to have deviated from his course to go in search of water. Today, refreshment stands are set up by athletic associations and jogging clubs.

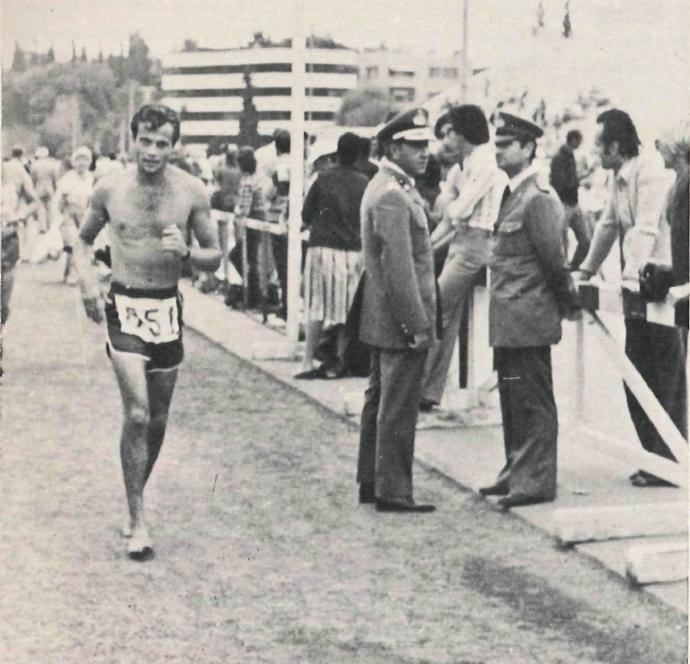

There was a bright sun and gentle breeze when I and the other runners assembled at Marathon. Despite the subtle undercurrents of anxiety, a sense of adventure, excitement, and challenge prevailed. At precisely twelve noon, a shot was fired signalling the beginning of the race. Suddenly, I was swept into a massive wave of bodies surging forward at a rapid pace, my unshodden feet surrounded by a sea of heavy footgear. But we all managed to set off without incident. The cheering was stimulating, the pace acceptable, and the camaraderie of the other runners comforting. I was somewhat disconcerted by the nonstop stream of determined runners passing ahead of me—men and women of all ages, and in all sizes and shapes—and the various reactions of my fellow runners and observers at the sidelines to my bare feet. Some looked aghast, others laughed, and a few offered expressions of sympathy.

As I circled the tall, earth tumulus marking the burial place of the Athenians who died during the Battle of Marathon, my spirits rose. The artifacts have long since been removed from the tumulus and transferred to museums, but the thought that two and a half thousand years after that famous event people from all over the world were covering the same ground, each clutching the traditional olive branch, was an exhilarating and stirring experience.

Crossing the flat plain of Marathon required little effort, but by the ten mile marker I began to doubt my stamina. My knees were beginning to ache, and I was disheartened by the fact that I had not passed a single runner, although many had sprinted past me, including a number of nimble-footed octogenarians. I began to realize the gravity of my undertaking. Other runners were stopping at stands for oranges, soft drinks, water, rubdowns, or just to take a break. Since many belonged to clubs, there was a team spirit to boost their morale. My solitude began to effect me. Time was not a compelling factor, since there was no one against whom I could pace myself. And the sensation of thirst was growing intolerable.

The sun was beating down relentlessly as the fifteen mile marker fell behind me and graded hills loomed ahead. I had discovered during my brief training period that I was good on hills. Although my legs and thighs were aching, my confidence was bolstered when I saw many runners slowing down to a walk on the hills. I trudged onward. By the time I reached the eighteen-mile point my legs were numb and I was feverishly hot. Spotting a small pool of water that had been formed by a leaking pipe, I crawled over to it on all fours and splashed myself, but did not drink. I pushed on. As a result of the break in my stride, my muscles felt knotted, and only some instinctive drive urged me forward. I remembered Lucilius’s satirical description of a runner named Marcus who moved so slowly that he was still running long after the others had completed the race. The caretaker of the stadium mistook him for a statue and so closed the stadium. When it was re-opened the next morning, Marcus was still running, not having completed the laps. I began to feel like Marcus.

There were few bystanders now along the route to cheer runners on and unlike that first runner from Marathon, I did not have any lofty mission to spur me on. But no doubt he too had been overwhelmed by the sheer hardship of pushing one’s body beyond its physiological limits. As I became only semi-conscious of the agony to which I had subjected my body, I saw Lykavitos and the Parthenon in the distance and all thought and pain were replaced by an overwhelming drive to push onward. The capacity of my cardiovascular system seemed rejuvenated as I neared the goal.

At last, I was passing other runners. Suddenly, a mile before the finish line at the Olympic Stadium, I was overcome with an illogical urge to cry. Suppressing the feeling, I fixed my attention on the next runner to be passed, and then on the next. Time passed so quickly and I moved ahead so mechanically that I was hardly aware that I had entered the massive, marble-lined stadium and crossed the finish line until I was embraced by relatives and friends. I later learned that I had passed some twenty-three runners during the last two miles.

Within half an hour, my vital signs were within normal limits although my lower extremities were in a painful state of temporary paralysis. Seated on the warm marble tiers of the stadium built for the first Olympic Games in 1896,1 watched the seemingly endless line of runners finish the race, and pondered the forces that motivate such feats. The poet Oppian wrote on the subject sixteen hundred years ago: “As runners on the track, leaping forward from the start and urging their swift limbs ever on and on, raise clouds of dust in their eagerness to reach the distant post; each of them longs to win through to the finish to receive the sweet reward of success, to force his way first to the line and place on his brow the victor’s wreath.”

I wasn’t sure how long it had taken me to run the course from Marathon to Athens, or where I placed. It didn’t seem to matter.