Photographs by Margot Granitsas

Accessible to each other on the gentle Gulf of Volos side, on the wild, Aegean side, where the mountains drop to the sea in precipitous cliffs, the villages are isolated from each other, lying at the end of long winding roads which cut deep into the mountains, or on the few main roads leading over passes.

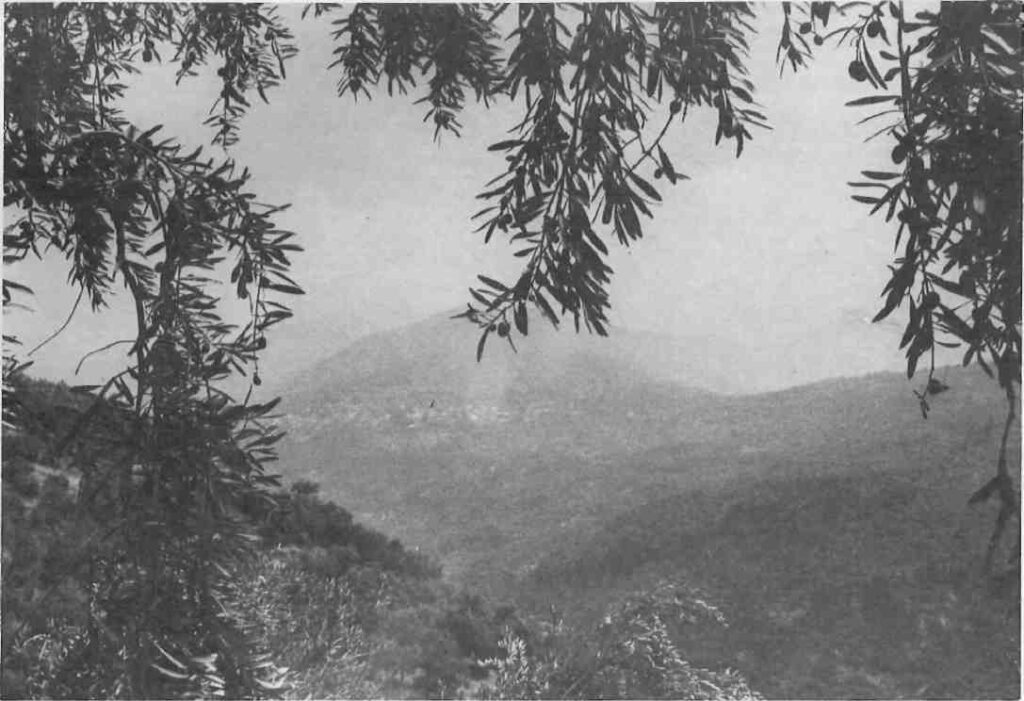

Cascading waterfalls, singing tree-tops, and lush green slopes may not fit the image of “typical” Greece, but these refreshing sights and sounds come to mind when remembering summer days spent crisscrossing Pilion. Yet it is a Mediterranean landscape, often reminiscent of Provence, of Tuscany, of villages as far north as the Ticino. In the Spring and Autumn, violent storms bring heavy rainfalls nourishing the apple, peach and pear orchards that climb up from the seacoast. In Winter, the impenetrable blackberry thickets with their sweet fruit, the forests of oak and chestnut trees, turn to a bright ochre. Throughout the year, the immense olive groves stretch silver-green and shimmering over the soft rounded foothills. The green mountains, the spectacular views from their crests, the cool summer nights, the skiing in winter, and the charming villages attract increasing numbers of visitors.

The first known settlements of agricultural people in Europe were in Thessaly. Important neolithic and late neolithic excavations have been made at the nearby ancient sites of Sesklo and Dimini. Many traces of independent Mycenaean settlements have been found at Pagasai and at Iolkos, celebrated in mythology as the home of Jason and by tradition the point from which the Argonauts set off on their expedition to recover the Golden Fleece.

At Iolkos, which is today just a suburb of the modern town of Volos, preliminary excavations strongly suggest that it was the site of a major Mycenaean palace. The importance of the area declined during the Persian Wars, but in 293 B.C. Demetrius I of Macedonia built the city of Demetrias in a bay outside Volos. Because of its location and massive fortifications, it became an important military and commercial centre. The Agora (market place), large sections of the walls, the theatre, as well as ruins of the palace attest to its significance.

During the Byzantine period, the towns succumbed slowly to the waves of invasions from the North. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, hermit colonies were founded on Pilion, probably by monks fleeing from Mount Athos. Eventually, the peasants who worked their fields around these monastic colonies began to seek their protection and small settlements grew up around the monasteries, taking their saints’ names: Agios Lavrentios, Agios Georgios, Agios Yiannis, Agios Vlasios.

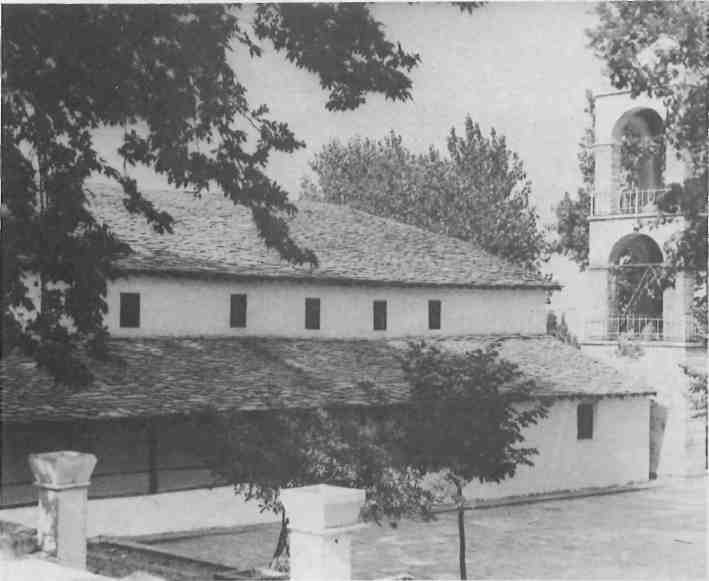

Under the Ottoman Empire, these settlements were largely self-governing, their affairs being run by the village elders. The Turkish overseers, living within the fortress of Golos (the site of today’s Volos), seldom ventured into Pilion, content to receive the tributes paid to them by the villages. Artisans and merchants arrived from other areas, swelling the population. It was then that a very specific architecture developed, most evident today in the typical Pilion (“pilioritiko”) houses and the distinctive style of the squat, low-sitting churches.

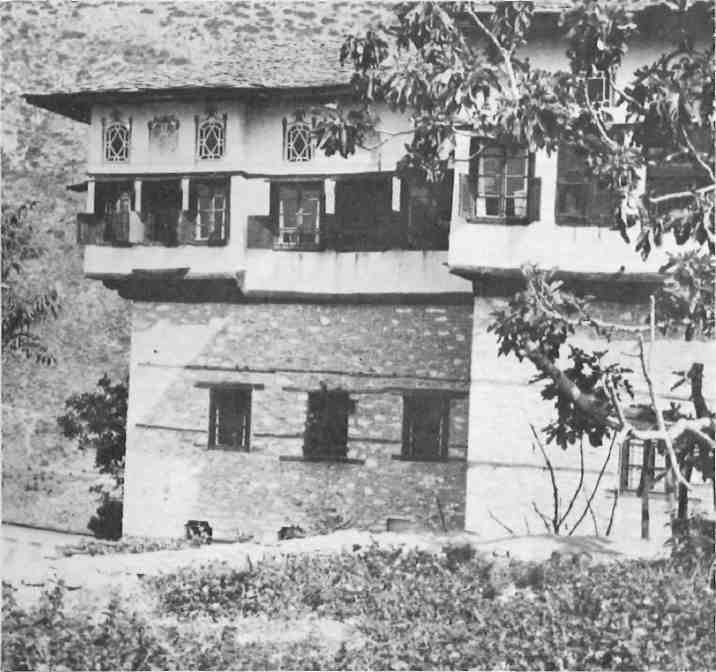

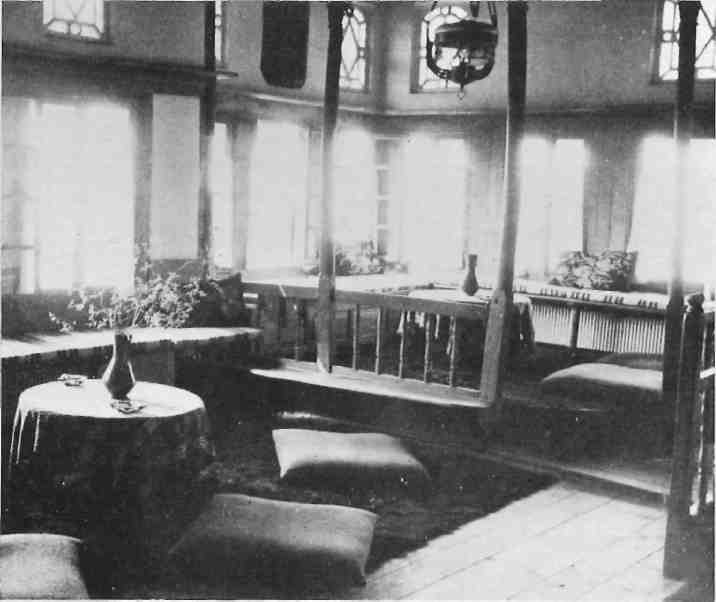

In 1668, Sultan Mohammed granted special privileges to the Pilion settlements. In 1774, as a result of a Russian-Turkish treaty, Greeks were given the right to sail their ships under the Russian flag in the Aegean and the Black Sea. The isolation of the villages thus ended and the existing trade in wool and silk fabrics expanded. As the merchants grew wealthy, they built large homes in the particular architectural style that had evolved. These stone houses, clinging to the steep slopes, characteristically have two lower floors with small, iron-barred windows. A third floor, built of lighter material and extending out over the lower floors, houses the kathistiko, a large, airy living room with benches covered with blankets and pillows, its many windows intricately shuttered to regulate light and heat. Sections of the shutters open sideways, but the upper parts open upwards to form an awning-like extension over the window. On the outside walls, beneath overhanging, gently-sloping, slate roofs, and over the windows, are painted decorations, often showing oriental influences. Frequently a frieze covers the entire front wall above the windows, sometimes depicting imaginary scenes or views of Constantinople. The inside walls of the wealthier houses were decorated with paintings as well, and in some the ceilings were beautifully carved and brightly painted.

To meet the building demand, artisans were imported, mainly from Epirus. They developed an uninhibited style, full of fantasy and imagination. Often crude, the woodwork and stonework exude insouciance. Itinerant artists such as Konstantis Pagonis, who painted many village churches and house interiors, and, in later years, Theophilos, left a large bulk of their work in these villages. Surviving examples suggest a fruitful interchange between the profane and sacred.

As the importance of the villages grew and interest turned to education and the arts, important centres of learning developed. One of these was Zagora, the capital of the Pilion villages. Rigas Pheraios, the revolutionary poet and national hero, grew up here. The library at Milies houses a unique collection of old manuscripts and first editions given to it by its native son, Anthimos Gazis, who lived for many years as a savant in Vienna, and was a hero of the Greek War of Independence.

As trade grew, the merchants needed a larger port. At the site of the old fortress of Golos, the modern town of Volos grew into a significant outlet. (The present harbour was built in 1912.) This brought about the decline of the villages. As the merchants moved to the new town, their houses were abandoned and fell into disrepair. Volos is today an important industrial trading centre, playing an ever-increasing role in Greek economic life, and considered a city with a great growth potential.

The Pilion area is linked to numerous Greek myths, some of which are increasingly regarded as guides to actual history. The Argonauts’ quest for the Golden Fleece, for example, is placed by archaeologists and historians at around 1500 B.C. According to mythology, it was on Mount Pilion that Apollo met Cyrene, the ardent huntress, and watched her wrestling with a lion. He fell in love with her, carrying her off to Libya where the city of Cyrene was founded. Peleus, commander of the Myrmidons, an army of ants that had turned into warriors, and Thetis, daughter of Nereus, a god of the sea, were said to have been married on Pilion. Both Zeus and Poseidon had desired Thetis but a prediction that her son would be greater than his father made them retreat. In her quest for the immortal child, Thetis either threw each newborn child she had into the fire or scalded it. After the birth of her seventh child, Peleus finally managed to deter her from this cruel test, and the boy survived as Achilles. Pilion was also the home of the wild, half man and half horse centaurs. Invited to the wedding of King Pirithous, King of the Lapithae, with Hippodamia, the centaurs got drunk and tried to seduce the women, including the bride herself. On another drunken occasion they had the temerity to attack Heracles who, not surprisingly, slew many of them and drove the rest away. A centaur with more gentle traits was Chiron who lived in his lair under the summit of Mount Pilion. He is said to have taught Jason, Achilles, and Asklepios, instructing them in riding, hunting, playing the lute, and imparting to them his medicinal knowledge of herbs and plants. Zeus rewarded him for his good deeds by letting him shine forever as a constellation in the firmament.

All that remains today of Pilion’s immediate past are the Byzantine churches, remnants of the old monas-teries and hermitages, and the beautifully-embellished eighteenth and nineteenth century village houses. And precious little it is, to judge from old etchings and drawings, which show Portaria, Zagora, Milies, Visitsa, Lehonia, Tsagarada, as magnificent settlements with an abundance of stately mansions, not unlike middle-European medieval towns. In this century, two events further decimated the population. During the Second World War, some of the villages suffered heavily from reprisals for guerrilla attacks made on German occupation troops. In Drakia, one hundred and fourteen villagers were shot. Many houses were burned down at that time and, in 1955, a major earthquake added damage to the old houses already in disrepair.

In the last few years, a major effort has been made to preserve what is left. The National Tourist Organization (EOT) has introduced a program to encourage local artisans to work in the traditional manner and cater less to tourism and all its gaudy manifestations, which are so evident in the “antique” shops lining the road leading to the magnificent square in Makrinitsa, or to Portaria. Another EOT project involves the preservation of traditional village houses in Visitsa, where ten old mansions are being restored as guest houses. In Makrinitsa, the Mousli family house has been completely restored, furnished with local handicrafts and homespuns, and is operating as a guest house. In Milies, one of the few remaining houses has been bought by EOT for future restoration.

Regulations have been introduced to guarantee that old houses are reconstructed and new ones rebuilt in the traditional style, but using modern construction methods and materials to make them earthquake resistant. One wishes that the authorities had taken action before the three – and four -storied charmless, concrete bunkers went up; or the Miami-style condominiums at Malaki on the coastal road, complete with polka-dotted mushroom garden lamps; or the kidney-shaped swimming pool in a private courtyard (although fairly well hidden) a few steps below Makrinitsa’s beautiful square with its majestic, century-old plane trees.

As the local people have moved to the cities in quest of work and more comfort, they have been replaced by people from the cities in search of country retreats. The Pilion villages have increasingly attracted people from Volos, as well as from Athens and Thessaloniki. The unique character of the area makes the long drive worth the effort. Some of these new inhabitants have been extremely conscious of the area’s heritage and have made great efforts to preserve its character. They are more inclined to use local materials and can better afford them. Villagers tend to use cheaper, more quickly-installed substitutes which drastically change the image of the village.

Although Pilion’s fascination is inescapable, life there takes some effort. Everything must be hauled from the road, often up or down steep, uneven and arduous stone-paved walkways. Nor are the beaches easily accessible. On the Aegean side it may involve a treacherous drive on winding dirt roads, or a long walk through olive groves to coves by the sea. Pilion is for those who like to walk, who do not mind climbing mule paths or up the mountainside, and are not fearful of getting lost when venturing forth in search of a road which may appear on the map, but does not really exist yet.