Beyond the iron doors, the visitor, if he arrives early enough on a Sunday morning, may observe one of the oldest and most interesting Christian liturgies, performed before a small congregation of faithful. Most are recent refugees from Muslim-dominated Iraq and Turkey, and from the fighting in Beirut.

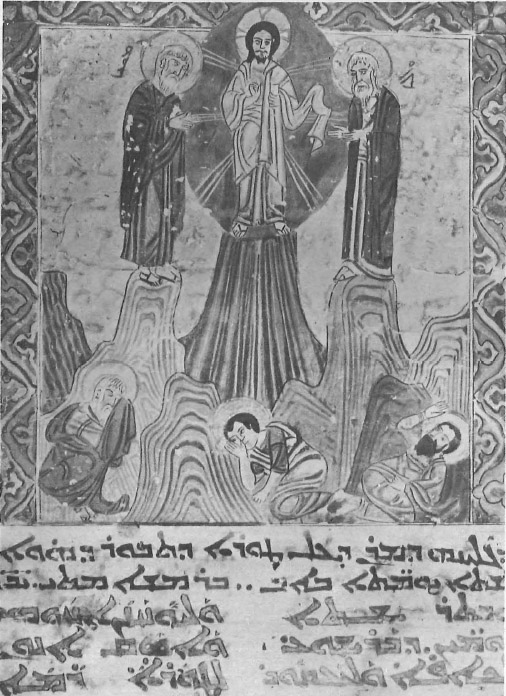

The term “Assyrian” is essentially a geographic one, referring to the ancient kingdom on the Upper Tigris which between the eleventh and seventh centuries B.C. was the centre of the great Assyrian Empire. Today the term embraces the Assyrian nation, and encompasses the belief of many Oriental Christians that they are the direct descendants of the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations that at one time dominated the ancient world. There are five Assyrian (or Syrian) churches whose common denominator is the use in their liturgies of the Syriac language — the lingua franca of the Middle East at the time of Christ who undoubtedly spoke Syriac and not Hebrew. The oldest branch is the so-called Assyrian Church of the East to which the church in Aegalio and its priest belong. It stems from the Nestorian heresy, one of the Christological controversies of the fifth century, condemned by the Council of Ephesus in 431, and abhorred by Orthodoxy because of its suspected links with the older heresy of Arianism. The second Church, that of the Western Syrians, or Syrian Jacobites (after a prominent missionary named Jacob Bardaeus of Edessa, now Urfa in southern Turkey), developed out of the Monophysite heresy — a theological antithesis to Nestorianism — which was condemned by Orthodoxy at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 after having spawned two other separatist churches, the Copts of Egypt, and the Armenian Gregorians of Asia Minor. Each rejected the authority of the Greek Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople, and established its own hierarchy. The Western Syrians recognized their own Patriarch of Antioch. The Assyrians (Nestorians), who lived for the most part outside Byzantine control in Mesopotamia — which was a part of the Persian Empire — looked towards their own Catholicos (primate) in the imperial capital of Ctesiphon, and later, following the Arab conquest, at Baghdad.

The sixth century saw several attempts to find a synthesis that would bring the Syrian Christians back to Orthodoxy. The apparent success of the Emperor Heraclius in the seventh century, however, resulted in yet another heresy, that of the Monothe-lites. It, too, was condemned by the Church in Constantinople, but not before a number of Syrians, followers of one Saint Maro (hence their name, Maronites), adopted it, and quickly retreated from their original home in the Orontes Valley to the security of the mountain fastness of Lebanon.

During the period of Arab greatness in the Middle Ages, both the Syrian Jacobite and Assyrian Nestorian Churches prospered under the traditionally tolerant Islamic rule. The Assyrian Church sent missionaries as far afield as China and India, and, before the coming of the Mongols, was the dominant religion in many parts of Central Asia. The ravages of Genghis Khan in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and Tamerlane in the fourteenth, however, drove the Christians of the Mesopotamian plain into the refuge of the Zagros Mountains in what is today Turkey’s district of Hakkari.

The Church of Rome and Constantinople had meanwhile split. During the period of the Crusades, when Catholic armies occupied the coast of Syria for nearly two hundred years, the Roman Church developed a strong interest in bringing Syrian Christianity into the Catholic fold. The Maronites of Lebanon were converted in 1180. Although they have maintained their Syriac liturgy, they have remained faithful to Rome to the present day. Among the Jacobites and Nestorians, the Catholics’ efforts were not as successful. They did manage, however, to establish Catholic factions in each community with their own rite and patriarch. Gradually, many Jacobites became Syrian-rite Catholics, and members of the Assyrian community converted to the Catholic Chaldaean rite.

Western Protestants also began to minister to these remote bands of early Christians in the nineteenth century. They were particularly attracted to the Assyrians who, unlike other Eastern Christians, deplored icons, crucifixes, and other ecclesiastical adornments, worshipped in plain, white-washed churches, and emphasized the reading of the Scriptures. In the early 1830s, American missionaries from New England established schools and hospitals at Urumiyya on the Eastern Persian slope of the Zagros, and brought many Assyrians into a native Protestant community. In 1886 the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury sent a mission to the Assyrians. His intention was not to proselytize, but, rather, to strengthen the existing Church and its organization. Largely because of this close association, the Assyrians, hardy mountaineers with a tribal tradition of fighting their hostile Turkish and Kurdish Muslim neighbours, rebelled against the Ottoman armies in World War I and proclaimed themselves allies of the British. They were no match for the overwhelmingly larger Muslim forces. With the withdrawal of the Czarist Russian Army from Anatolia after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the Assyrians were driven out of the Zagros following the murder of their Patriarch in 1918.

Only about half of the hundred-thousand members of the Assyrian community reached the safety of British lines near Baghdad. Once there, they were allowed to resettle in the British-administered Mandate of Iraq where they formed the Assyrian Levies — soldiers used by the British to keep the Arab and Kurdish Muslim population under control. Once Iraq became independent in 1932, however, and the British withdrew to the tew remaining bases, the Iraqis turned on the Assyrians in a series of bloody incidents, prompting many of the survivors to flee to the friendlier surroundings of French-administered Syria and Lebanon. Others followed their Patriarch, the youthful Mar Shamun, to the United States, where large communities were established in Chicago, Detroit, and San Francisco. Thereafter, the Church split into factions, supporting either the exiled Patriarch or a claimant stillliving at the time in Baghdad. The Patriarch was murdered in California in 1975 shortly after he took a young wife (contrary to Assyrian tradition which permits its priests but not its bishops and patriarchs to marry). A new Patriarch was recently chosen (in England, with Anglican assistance) and has returned to Baghdad after a patriarchal absence of over four decades. Division in the Church continues, and the political climate in Iraq is such that many Assyrians, Chaldeans, Syrian Jacobites, and Syrian Catholics have left or are trying to leave.

There are probably four-hundred-thousand Christians in Iraq out of a total population of twelve million. The majority are Chaldaean Catholics, but according to Vatican sources, at least one-hundred-thousand are Assyrians. Although no Assyrians remain in Turkey, there are still about seventy-thousand Syrian Jacobites and a few thousand Chaldaeans. Deeply attached to their ancient form of Christianity, and thoroughly pro-West in their political views, they are anxious to leave, but to where?

The community in Athens numbers about three thousand, and the worshipers at St. Mary’s represent four of the five branches of the Syrian Church (the Maronites of Lebanon are also found in Athens in some number, but keep to themselves or associate with other Lebanese Christians). A dozen or more Assyrian families came to Greece from Turkey with the Population Exchange of 1922-23 and have long since adopted Greek nationality. The great majority of Assyrian Christians in Aegalio are very recent arrivals. They were given refugee status by the Greek Government at the time of the Christian exodus from Lebanon two and three years ago. All are concentrated around their small church. They work at menial jobs and are often unable to obtain work permits. They remain hopeful of emigrating to Australia, Canada, or the United States. A hard-working, thoroughly honest people, they are grateful to Greece for giving them a home, however temporary, but bitter about the persecution of their co-religionists in Turkey and Iraq. Life revolves around the little church in Aegalio. They are often hard pressed to find the eight thousand drachmas needed to pay the rent each month, but they see their church as the focus of their exile abroad. It is an austere, unheated, cement-block building with a few tattered rugs on the floor, and the odd icon or cheap religious print on the wall, donated by sympathetic Greeks who don’t understand that Assyrians would be happier without such images. Yet it is here that they meet to exchange news of families scattered around the world, converse in their native Syriac, and discuss their rather spare hopes for the immediate future.

Their priest, Father Khuri, was sent to Athens two years ago by the Assyrian Bishop of Beirut to look after the community here. He lives in a bare, ground-floor apartment near the church which is always open to members of his parish. He also works with representatives of the World Council of Churches in Athens who have tried to help feed and clothe the poorest of the refugees, and to assist them in obtaining the necessary visas for immigration to a permanent home in North America or Australia. With so many doors closed to them, however, it is probable that the majority will remain here, and that their tiny church will continue to remind us that Athens is the gateway to the Middle East, and that in many ways it is a direct part of it.