Sue Andonio is not a tour guide. The group she welcomed on August 27 to “Greece Through New Eyes” was not made up of typical tourists. The forty women and five men assembled on the roof-garden of an Athenian hotel had come from as far as Japan for a travel experiment, a two-week tour designed by the Women’s Union of Greece (EGE) to focus on the Greek woman, her history, and her status today in this heartland of both matriarchy and machismo.

“This is the first time anything like this has been tried, by any women’s group in the world,” Andonio, EGE Executive Board and International Relations Committee member, tells the foreign participants as they sip their first ouzos against the backdrop of city lights.

“We wanted to have the Acropolis lit up for you in honour of the historic occasion, but our Union isn’t that powerful yet. We’ve only just started.”

The Union was begun two years ago, when a group of women in the Pan-Hellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) saw the need for a means to politicize the Greek woman, to fight her oppression, and to work for broad social change. As the Union grew, its leaders thought Greek women could gain from an exchange with foreign feminist activists. “Greece Through New Eyes” proved a good way to make the connection.

EGE sent trip brochures to women’s organizations all over the world. As a result, a group of experienced feminists gathered in Athens. After Andonio’s welcome, they stood and introduced themselves. Kari Bull is the Political Secretary for Women’s Affairs of the Socialist Left Party of Norway, and an Oslo town counselor. Lisa Cobbs is the twenty-two-year-old managing editor of San Diego, California’s feminist newspaper, The Longest Revolution. Kay McPhearson is the President of Canada’s National Committee for Action on the Status of Women. Geraldine Harcourt is a New Zealander living in Japan and organizing Tokyo’s first International Women’s Film Festival. Barbro Hellberg produces radio shows about women for the Swedish Broadcasting Company. Eveline Bernstein runs a shelter for battered women in Santa Cruz, California. Four men came with their wives, and, along with one single male, they made a good-natured minority.

The introductions and the official greetings over, the roof garden is a buzz of conversations between EGE members and the foreign guests — about women in politics, women in media, the status of women’s movements. The Union members who have worked for more than a year planning the tour nod and smile to each other. This is just the beginning they have hoped for.

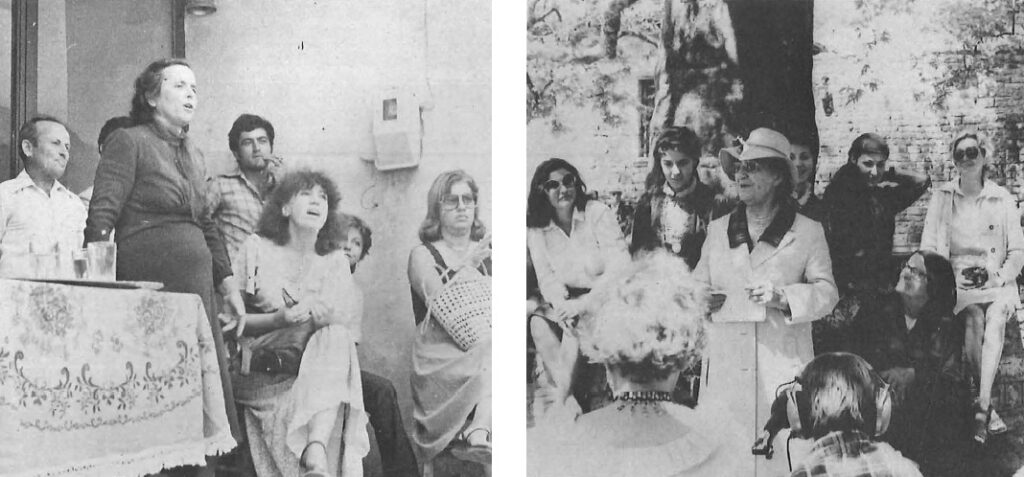

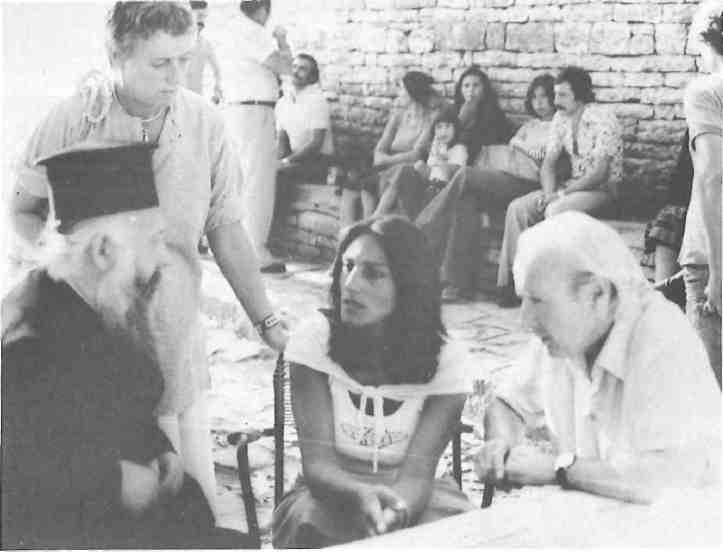

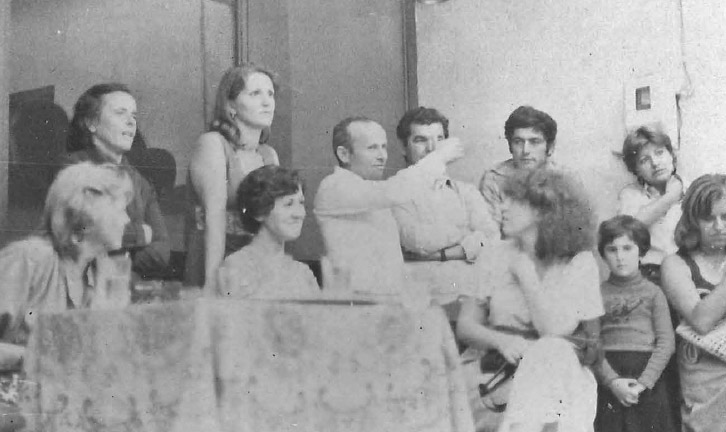

On Sunday afternoon the coach pulls into Karies, a town of shepherds and farmers in northwestern Greece near the Albanian border. Two hundred villagers are waiting in front of the elementary school. The men, women, and children, many still in their Sunday best, eye the foreigners coming from the tour bus to meet them. The President of the Community calls the meeting to order from the concrete square that will serve as a speakers’ platform and, through an EGE translator, thanks the visitors for choosing Karies to learn about the rural Greek woman. Then, two members of the EGE chapter in the nearby city of loannina speak to the foreigners and the villagers about the hard work, unrewarded by government services, of women in villages such as Karies throughout rural Greece.

The country woman’s plight really hits home, though, when villager Anna Barka describes her day’s activities. Anna wakes up at four a.m. to help her husband lead their sheep in the dark to their pastures, which are five kilometres from Karies because land closer to their home is too expensive. She walks back alone to make breakfast for her four children and to get them ready for their school- and work-days. After they leave, when she is not cooking lunch or dinner, Anna cleans the house, washes ‘the clothes by hand, weaves cloth for the family and for her daughters’ doweries, cares for the mules, and tills the fields.

What does her husband do, one of the guests asks through a translator, after they take the sheep out to pasture? “He sits with the sheep all day.” What time does Anna go to sleep, asks another. “At ten,” she answers, “exhausted.” How old is she? “Thirty-nine.” The foreigners gasp, unbelieving. A member of Ioannina’s EGE nods her head and sighs. “Yes, it’s true, though she looks almost sixty.” Does the village have medical services? “No. We have to go to the hospital in loannina by public bus. I gave birth in my house with just a friend there to help me.” What is Anna’s dream? “To live a better life,” she* says, looking toward the rugged mountain that looms above Karies. “But here, in the village.. Not elsewhere.”

Kalyra, twenty-seven, tells the group she would also like to stay in Karies, but that the conditions make it impossible. “Maybe if they’d build a factory here,” she says. “The field work doesn’t bring in enough money.” Now that her two sons are growing up, she plans to move to a town where they can attend a good high school. “I want my children to have a future.”

Papandreou; sixteen-year-old Vassiliki, and Sue Andonio. Standing: Anna Barka and Kalyra.

Kalyra asks if the foreigners can tell them about farm women in their own countries. American Eveline Bernstein explains that their problems are very similar to those of the Greek country woman. Small farming families leave their fields for the cities as they do in Greece because they cannot compete with the big farm complexes. “My sister was a farmer’s wife in Indiana,” says Bernstein. “She died at the age of thirty-nine. She worked herself to death trying to make it.” As the villagers hear this in translation, they look with surprise and respect at the American woman. The President of the Community explains, “We had no idea you had the same situation.”

One of the visitors asks if the group can speak with a young girl. Vassiliki, sixteen, agrees, when prodded, to come to the platform. Embarrassed at first, she opens up as she answers the questions. She says she travels by bus each day to a girls’ high school in loannina and wants to become a teacher. Is she going to leave Karies? “Yes, I want to go away from here.”

Where? “I don’t know. Somewhere I can find a job and study. Anywhere the conditions are better.” What does she think of the life of women of her mother’s generation? “It’s a very hard and unjust life.” And what does she think of EGE? “I like it that women are starting to get organized,” she says. “This is the first time that women from all over the world have come to discuss our problems.” As Vassiliki spoke, a girl of about eight walks onto the platform and whispers to Sue Andonio, “I want to join the Union.”

Monday morning, the bus heads beyond Karies up into the mountains of Pindos, where the Greeks waged a strong resistance during the Second World War against Italian and German invasions. The tour members point indignantly as they pass a woman stooped under a load of firewood. Her husband walks behind her, unburdened. Or when they see an old woman carrying bundles from town hobbling along the steep road trying to hitch a ride up to her village. They stop in Monodendri, one of the many once-prosperous villages in the region called Zahori. They walk up to the village square, past the large, old stone house to meet eighty-year-old Frosso Ioannidou, known as “the mother of Zahori” because of her leadership role in the villages. Ioannidou, who has written a book about Zahori’s women, recounts some tales from their history.

During the Turkish occupation, Zahori was a wealthy centre of learning, and its men, mostly merchants and scientists, went abroad to work after marrying. The women were left in the villages to administer family fortunes and lead Zahori’s large family clans. At a time when few Greek women could read or write, the Zahori matriarchs built the country’s first girls’ secondary schools and raised their daughters to be literate, shrewd businesswomen. When the first Turkish magistrate came to Monodendri, a woman of eighty visited him to present a civil damage suit. “The magistrate told his assistant, ‘Don’t leave. We’ll need you to sign the documents on behalf of the old woman.’ The woman stood up a.nd told him, ‘Not only am I able to sign, Mr. Magistrate, but I’ll read the text before signing it.”

Ioannidou moves from her foremothers to her own generation of Zahori women, who answered, in the winter of 1940, what she terms “the call of the fatherland”. When the Italians began their attack on Zahori, Ioannidou led her children away from the border to escape the heavy bombardment. On her way back to her home, she stopped at another village. “I noticed there were no women, only men, in the village,” she remembers. When she asked where the women were, an army major told her they were carrying guns, ammunition, and food to the troops at the top of the snow-covered mountains. “I couldn’t believe it. I told him, ‘Only deer can climb these mountains.’ But the Major told me the soldiers were pulling the women up the cliffs with ropes. As they went up and down, the women were throwing stones at the enemy.” Making her way toward Monodendri, Ioannidou found the same thing in all of the villages — women carrying supplies up the nearly impassable mountains, rebuilding destroyed roads and bridges in the winter rains, walking for miles to take messages between the front lines and army headquarters.

Greek women transporting supplies to the front lines during the Resistance.

“These women carried on their backs the burden of a giant effort. They wrote the epic of Pindos. But the Government has always ignored what we all know,” she says, bitterly. “When they turn down our requests for services, they tell us we’re not productive. I say, ‘We may not produce many onions, but we’ve given our blood for this country.'”

By the time they return south to the Hotel Akti Apollon near Sounion, the tour members are ready for a little conventional sunning and swimming. In ten days they have travelled from the seas off the island of Spetses, where the female sea-fighter, Bouboulina, captained her own ship during the War of Independence of 1821, to the northwestern cliff of Zalongo, where, according to legend, fifty-six women sang and danced their way to their death, throwing themselves and their children over the precipice rather than submit to Turkish enslavement. The visitors have seen much of Greece’s natural beauty and learned much about its folklore, but the view they have had of the society’s problems has not always made for a cheerful vacation.

The last couple of days of “Greece Through New Eyes” are not all relaxation, however. A series of seminars about issues facing today’s Greek women have been organized on the status of working women, family planning, abortion, and the Greek family code. The speakers explain that while EGE works on specific measures to improve the lot of women, the Union believes that women will be liberated only through basic changes in the country’s social and economic system.

“That’s why our struggle is one and the same,” says Canadian Betty Mardyros during a discussion of the status of the Greek working woman. “Women in all the capitalist countries are fighting the same battle, because the oppression of women is built into our economic system. We’ve made some gains in North America, but our situation is still not very different from yours here in Greece. We all have to be aware of this so we can prepare to fight it together.”

On the beach or the hotel patio, the foreigners and their new Greek friends speak about this common fight and share ideas about how to wage it. And the tour members speak about what they have seen through their travels.

“The Acropolis and the museums are nice,” says Thora Craig of Great Britain. “But we really saw some of the country. Sometimes I was so sad and angry, but I didn’t come here just to enjoy myself. I came to learn about the people.”