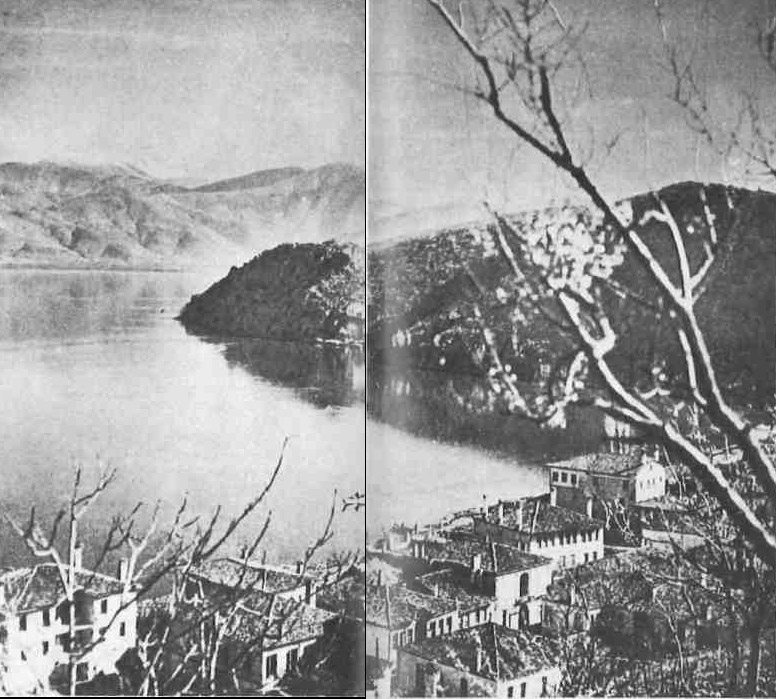

Situated in northwestern Greece near the Yugoslav border, Kastoria has long been noted for the unusual architecture of its houses and its more than seventy churches which made it one of the most beautiful cities in Greece. Five hundred kilometres from Athens and more than two hundred from Thessaloniki, it is located on the rocky neck of a peninsula that cuts deep into the dark waters of Lake Orestia which sits in a deep hollow surrounded by limestone mountains. Up until fifteen years ago the lake, which is also known as Lake Kastoria, provided the city’s water needs, and its inhabitants with an abundance of fish. Now its surface is covered with a green film in summers and swimming is forbidden although there is some hope that a major project will be undertaken to clean the lake and return it to its former clarity.

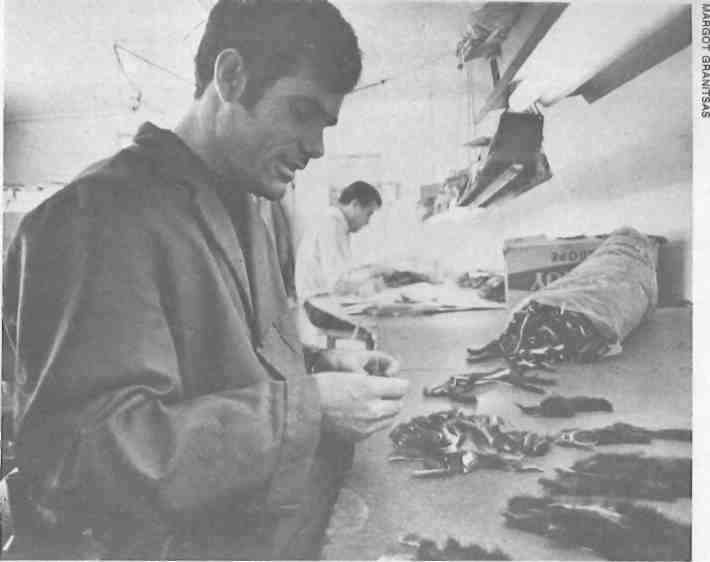

The fur industry for which it is famed is protected by a special regulation which grants to Kastoria and the nearby town of Siatista the exclusive rights to engage in this particular type of piecework. As a result, Kastoria has one of the highest per capita incomes in the country. Since 1951 the town’s population has grown from ten thousand to twenty-five thousand, and swells during the day with people who arrive from outlying areas to work at the shops where tiny remnants of fur, salvaged from larger pelts by manufacturers abroad and imported duty-free to Greece, are painstakingly separated, matched, and skillfully sewn together to form blanket-like “plates”. These are shipped to Athens or exported abroad where they are made into garments. Despite government protection of the industry, thousands of workshops function illegally throughout the countryside, often with the tacit consent of local officials. Whether or not the rights to engage in this aspect of the fur business should be extended to neighbouring towns and villages has become a major issue.

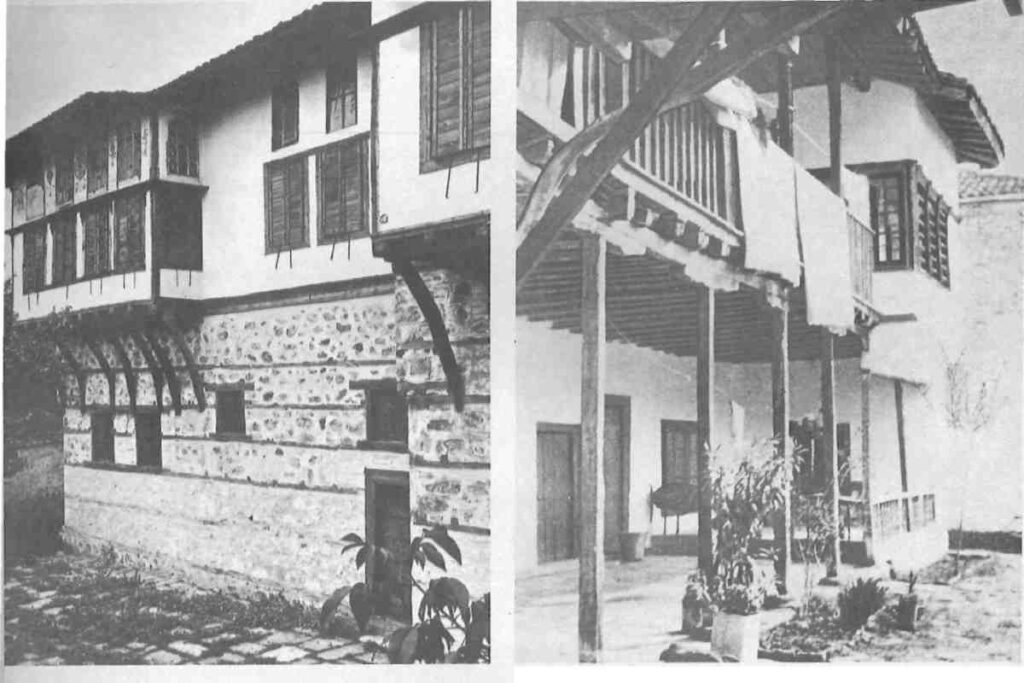

Prosperity, however, is threatening Kastoria’s architectural heritage as the lovely old buildings, once a source of pride, are gradually being torn down and replaced with faceless concrete structures. Only a few of the more notable buildings have been spared and these have been declared national monuments and are being restored by the National Tourist Organization. The lovely old mansions which still stand and the more than fifty surviving Byzantine and post-Byzantine churches which seem to grace every corner along the narrow streets testify to the former charm of the area.

According to some accounts, the name Kastoria derives from the mythological figure Castor, the twin brother of Pollux, who was said to have built the town. In all probability it derives from kastoris, the Greek word for beavers, which flourished in the area. Known in ancient times as Keletron, the town was captured by the Romans in 200 B.C. Transferred to its present site, it was briefly named Justinianopolis after the Emperor Justinian who is said to have built the wall which fortified the city in medieval times; sections of the wall still exist today. Kastoria was conquered by the Ottomans in 1385 and remained under Turkish domination until 1912.

Commerce in furs was begun more than five hundred years ago by a group of Jewish merchants who settled in the area and began trading with other Balkan countries, Central Europe, and eventually Asia. Despite the many hazards from brigands and thieves, the trade flourished bringing great wealth to the area and the Kastorians into contact with many other parts of the world. These contacts influenced their mode of life and their architecture. In response to this demand for more elaborate and ornate homes, a new class of craftsmen emerged — artisans, woodcarvers, painters, stone carvers, and builders — most of whom came from Epirus. Their work, rooted in Byzantine tradition, combined the distinctive characteristics of both the West and the East.

Today, most of the old mansions are to be found in what was formerly the Christian neighbourhood, called the doultso. In the past, each ethnic or religious group lived in separate enclaves. The buildings — most of them two- or three-storeys high — were constructed according to similar architectural plans. The exterior walls of the lower storeys are composed of stone reinforced by horizontal strips of wood and the upper storeys are built of lighter materials which are covered with limestone. Portions of the upper storey jut out beyond the lower floors, a feature characteristic of much Northern Greek architecture. The overhanging roofs are of red tiles and oak.

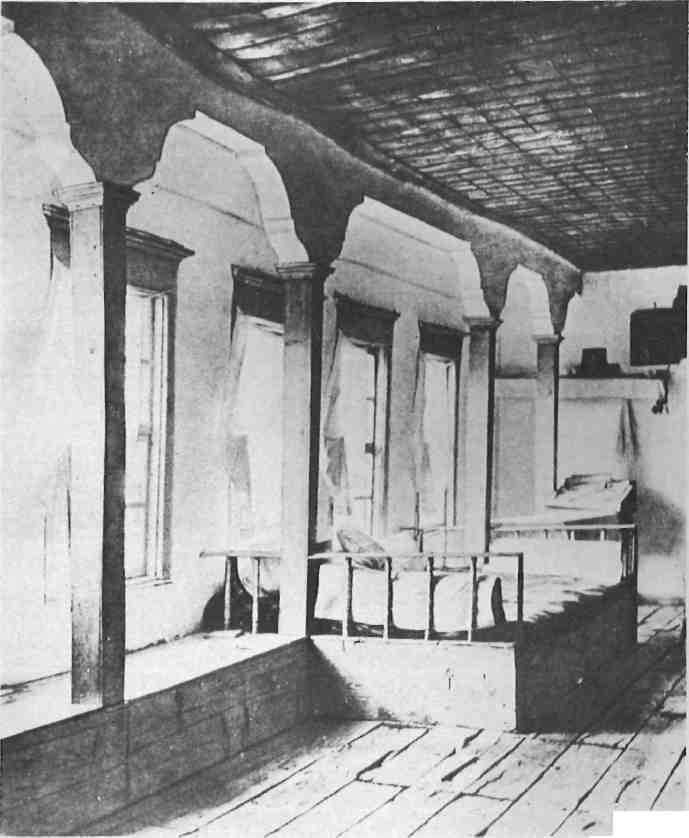

The double wooden doors of the main entrance lead into a windowless, flagstone vestibule lined on both sides with storage areas for food, wine and fuel, beyond which is a small garden enclosed by the kitchen, washing area, and oven. A narrow wooden staircase leads from the entrance to the first floor which could be sealed off at night for greater protection. It was here that families gathered during the cold months.

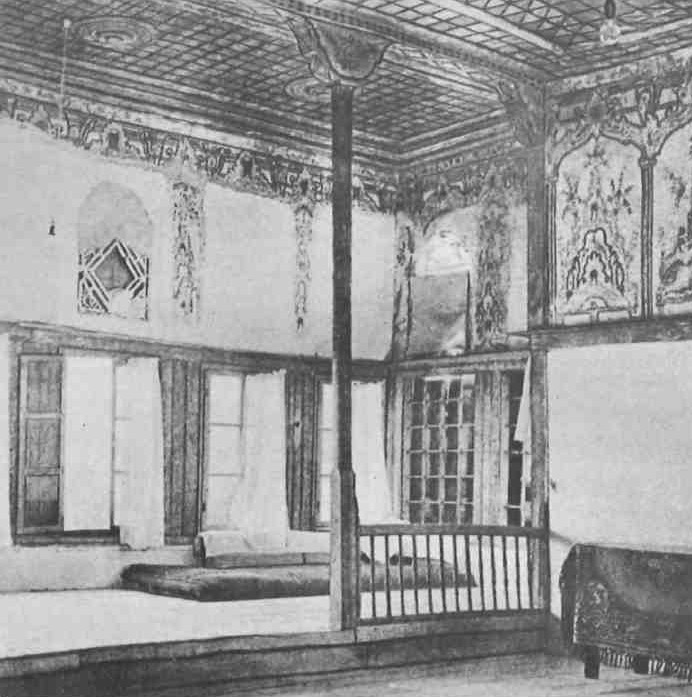

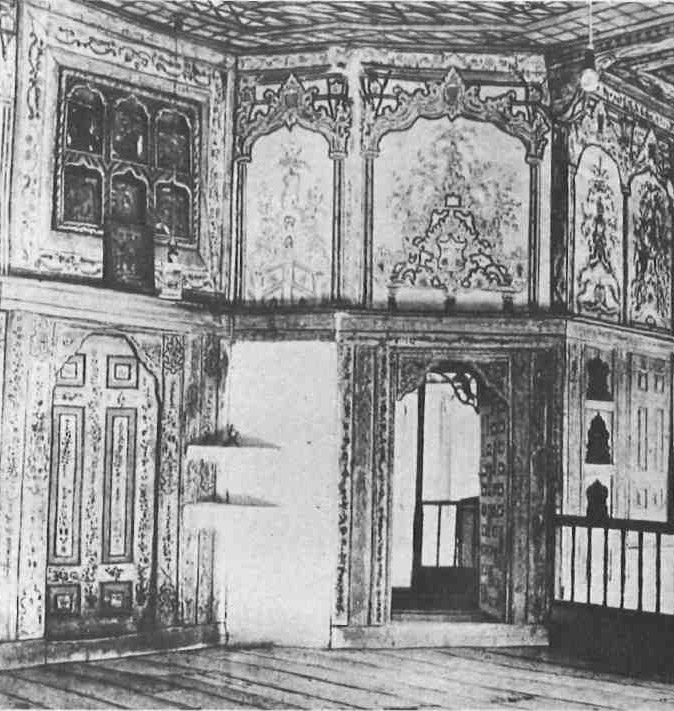

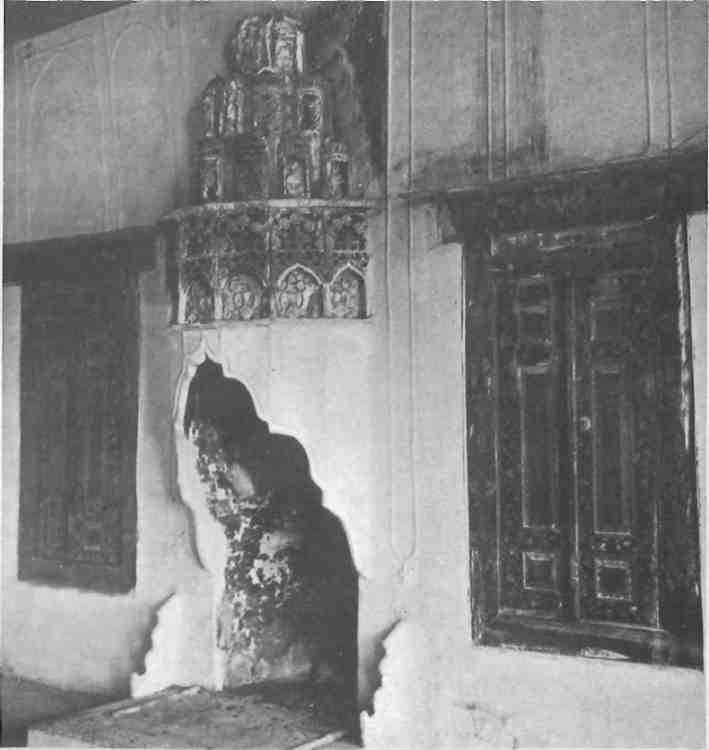

The Kastorian household consisted of an extended family with the sons and their families remaining in the paternal home. Each room on the first floor has its own elaborately-decorated fireplace projecting in a semi-cylindrical shape from the wall. In many rooms the walls were elaborately and brightly decorated with paintings. One wall of each room was panelled in wood behind which was an expanse of cupboard space. These also hid, in many cases, escape routes to be used in times of emergency. The windows facing the street were covered with iron grillwork offering further protection from attack. Overlooking the small garden is a wooden balcony where the women would sit in the sun giving it its name, iliakos from ilios.

The richly-decorated upper floors were used during the summer months and for receptions. At the top of the staircase there is usually a lattice-covered alcove for the musicians who entertained at family celebrations. A spacious main room, doxato, leads to a room on a higher level, the kioski, lined on three sides by low, straw mattresses which served as sofas, and were covered with red homespun or embroidered materials. Although sparsely furnished, this room, too, was invariably lavishly decorated. Double rows of windows line three walls, the first row decorated with wooden lattice work and equipped with shutters, and the upper row with magnificent stained glass, a remarkable and unusually beautiful feature of the Kastorian architecture. When the lower windows are shuttered the room is illuminated by the sunlight streaming through the multi-coloured flowers, geometrical patterns and inscriptions of the stained glass creating a dream-like atmosphere. The lavish decorations of the walls and the ceilings continue through the other rooms on this floor and are even richer in the formal sitting room where, once again, the fireplaces are elaborately decorated sometimes with frescoes showing intricate landscapes, and double rows of windows.

Two small rooms found in Kastoria homes distinctly reflect local customs. One overlooks the main reception room; from here the young, unmarried women of the household observed receptions and balls unseen behind a window. A similar room is usually behind the formal sitting room. From this vantage point young girls might listen to their fathers receive visitors — perhaps someone coming to ask for their hand in marriage. Such practices were clearly defined by local custom although they were not markedly different from those prevailing in other areas of Greece. (The betrothed never met until the day of the wedding, and arrangements were made between the two families with a matchmaker acting as intermediary.)

Except for those mansions which have been declared historical monuments, most are threatened with extinction. It is to be hoped that attempts will be made to preserve the vestiges of this unique aspect of our heritage and the rich legacy of Kastoria.