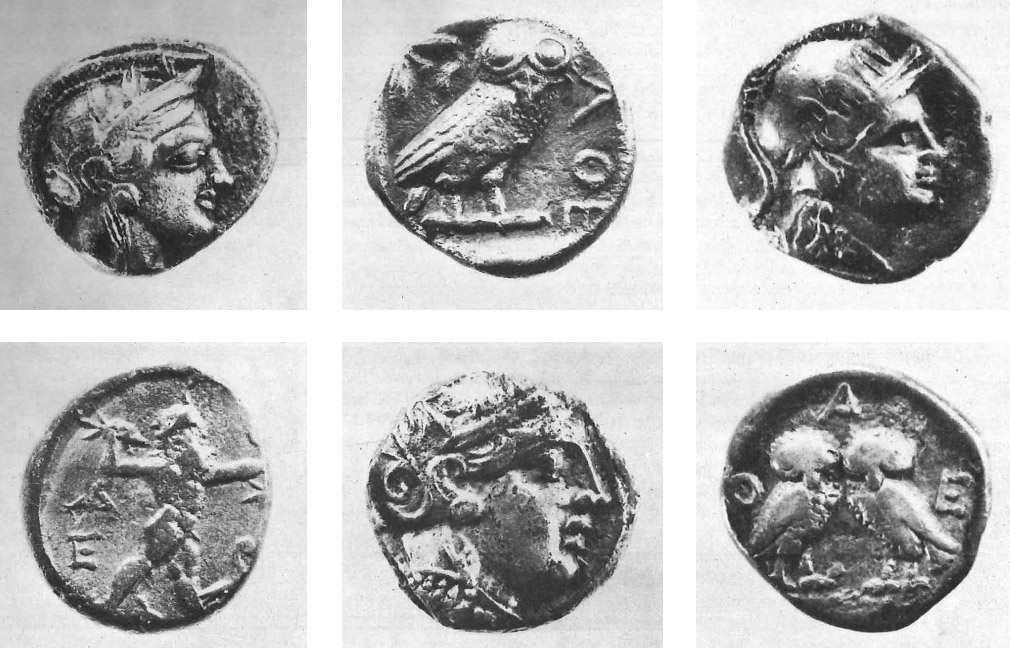

Ancient Greek coinage dates back to the sixth century B.C. Invented in Lydia, in Asia Minor, its use in Greece spread rapidly among the city-states. The earliest coins carried a single design on one side, with only the mark of the punch on the reverse. Soon, however, designs began appearing on both sides of the coins, showing a great range in types which often were symbols identifying the city which minted them. Particularly popular was the likeness of the tutelary deity of the city on the principal, or obverse, side of the coin. A symbol appropriate to the minting city would appear on the reverse side. This often took the form of one of the main products of the state, such as the wine jars depicted on the coins of Chios. Occasionally it was a punning reference to the name of the city itself, such as the rose which adorns the reverse of many coins from Rhodes (which means “rose”).

Although the scale of the coins was small, the artistic quality was generally very high, and ancient coins remain one of the most pleasing expressions of Greek art. They were clearly appreciated in antiquity as well; on many of the finest coins the die-cutter was allowed to engrave his signature. In addition to their value as works of art, they are source material for the art historian: many statues and temples now lost are known only through representations on coins.

Since many political events and military successes are reflected in the changing types, ancient coins are of considerable importance to the historian. For a current example of coinage reflecting shifting political realities, one need only reach into one’s pocket and pull out a handful of change. Although coins predating the demise of the dictatorship are gradually being withdrawn, many are still in circulation, and their different designs accurately reflect the historical events of the last twelve years: the monarchy under Constantine, the rise of the Junta, the dissolution of the monarchy, the Junta’s “democracy” (when the soldier disappears but the phoenix remains), and the restoration of true democracy. All these developments are represented in the coinage; similar historical events may be traced in the varying types of ancient Greek coins.

The coinage of ancient Athens was amongst the finest ever minted. On the obverse it carried the head of Athena, patroness of the city, and on the reverse her sacred symbols, the owl and olive sprig. Unlike many Greek coins, those of Athens changed little over the years. This was apparently due to the purity of the silver, which caused the coins to be prized for their bullion value throughout the ancient world; Athenian coins have been found in hoards as far away as Spain and India. As a result, both the coin types and their artistic styles were very conservative and remained unchanged for long periods of time, rather like the Maria Theresa thaler, another coin minted in exactly the same style for several hundred years because it was recognized, trusted, and accepted throughout the world. Athenian coins were similarly trusted and admired so the purity had to be maintained and guaranteed. A tremendous outcry arose in the late fifth century B.C. when, because of the exigencies of the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians introduced bronze into their coinage. The comic poet Aristophanes drew a parallel between the new, debased coinage and the second-rate politicians of his day in his play The Frogs, produced in 405 B.C.:

It has often struck our notice that the course

our city runs

Is the same toward men and money. She has

true and worthy sons:

She has good and ancient silver, she has good

and recent gold.

These are coins untouched by alloys,

everywhere their fame is told;

Not all Hellas holds their equal, not all

Barbary far and near,

Gold or silver, each well-minted, tested each

and ringing clear.

Yet we never use them! Others always pass

from hand to hand,

Sorry bronze just struck last week and

branded with a wretched brand.

So with men we know for upright, blameless

lives and noble names,

Trained in music and palaestra, freemen’s

choirs and freemen’s games,

These we spurn for men of bronze, for

red-haired things of unknown breed,

Rascal cubs of mongrel fathers — them we

use at every need.

In the fourth century, Athenian coins were so frequently copied and forged that an official tester sat among the banking tables in the Agora every day to test and guarantee the quality of the coins in circulation.

Unlike most Greek city-states, Athens had her own silver mines at Laurion on the east coast of Attica, and they were exploited from the sixth to fourth centuries B.C., primarily to provide silver for the coinage. Several of the mine galleries and many ore-washing establishments may still be seen today in the hills between Thorikos and Sounion. The mines were owned by the state and were leased out to private individuals. Copies of the contracts between the state and the mine operators were set up on large stone tablets and many have come to light in the excavations of the Agora. Silver bullion was brought up from the mines to Athens where it was minted into coins. In addition to the silver coins, special issues of gold and regular issues of bronze were produced as well.

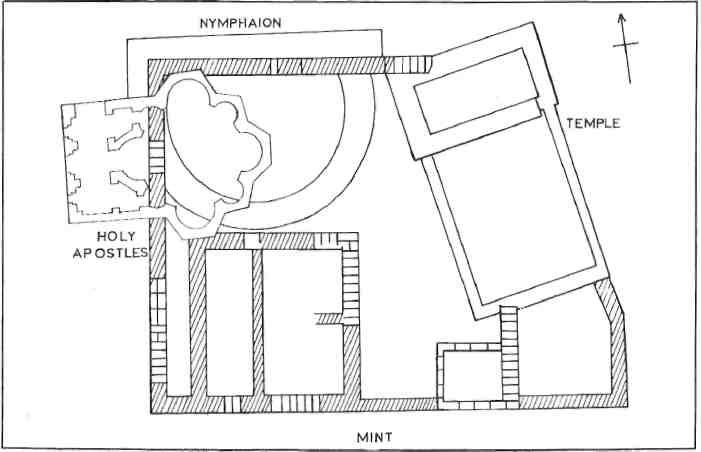

The mint of Athens which is being excavated this summer is located in the Agora, the civic centre of the ancient city, at the foot of the Acropolis. Digging at the site is being carried out by the American School of Classical Studies as part of its continuing exploration of the Athenian Agora. It is being financed by private donations, largely from the United States, supplemented by a grant from the Credit Bank of Greece because of the unique position of the mint of Athens in the history of ancient finance. It provides a rare opportunity, for despite thousands of coins which have survived from antiquity, only two other ancient mints are known, one at Halieis (modern Porto Heli in the Argolid) and the other at Olbia, in South Russia.

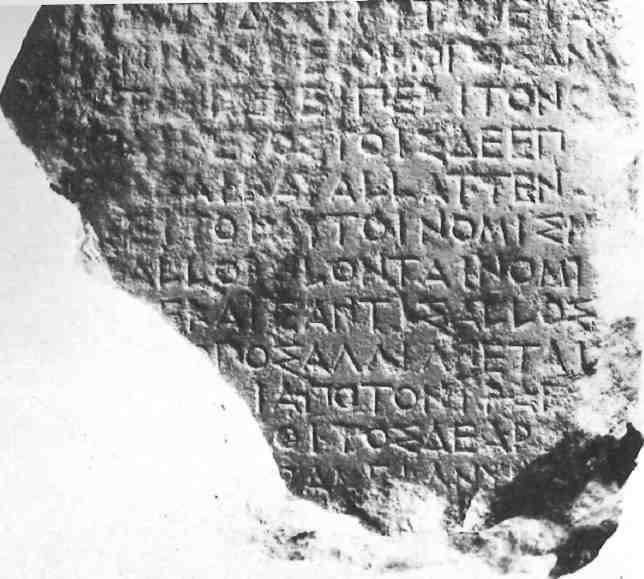

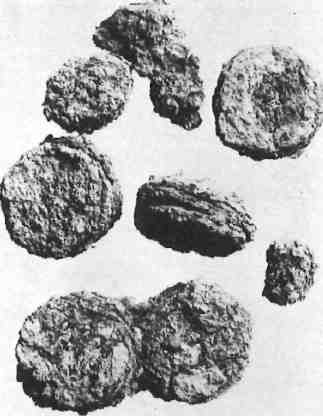

The identification of the site as the mint, first suggested several years ago after the preliminary exploration of the area, is based on several pieces of evidence. Most compelling was the discovery within the building of a cylindrical bronze rod and sixteen discs which had been chiseled from it. These discs seem to have been flans or blanks, intended to be struck into coins but never actually minted. In addition, signs of industrial activity in the area suggested that the final stages of refining metal were carried out in the building. Finally, three inscriptions concerned with the mint or minting activities were found in the general vicinity.

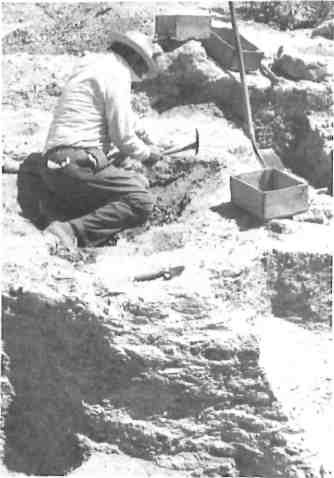

Half a dozen workmen can be seen every day just behind the little Byzantine church of the Holy Apostles, slowly digging away the stratified earth floors of the building, searching for more evidence concerning this important Athenian institution. The new excavations have thus far considerably strengthened the hitherto tentative identification. Some sixty new flans came to light in the first week of digging alone. Considerable industrial activity has been revealed as well in the form of small furnaces, water basins, layers of ash and carbonized wood, and fragments of waste and slag from the refining process. The evidence increases with each day of excavation.

The history of the building is coming into sharper focus as well. It now appears as though the mint was built in the late fifth century, about 400 B.C., and continued in use until the late first century B.C., a date which coincides with the beginning of a period, which lasted for over one hundred years, when Athens minted no coins of her own.

On the basis of the excavations this summer and the additional information available from literary texts, inscriptions, and ancient representations, a picture of this fascinating building is slowly emerging. Though poorly preserved today, it was a large structure, measuring some twenty-seven and one-half metres by forty metres, with foundations over a metre thick. The great thickness of the foundations can perhaps be attributed to a natural and proper concern for the security of the building since precious metals must have been stored there regularly. Details of the interior plan are still coming to light, but already it is clear that the building had several rooms as well as a courtyard left open to the sky. These will have served a variety of functions, reflecting the many uses of the building itself.

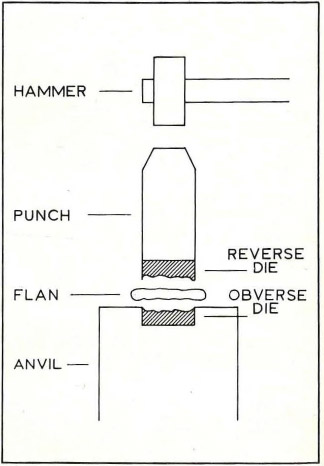

Most important, of course, was the minting activity, well represented now by the coin blanks and furnaces. Once the metal had been refined, the technique of minting was simple and all coins were made by hand. The blank round disc (or flan) was prepared, either by casting it in a mould or chiseling it off a cylindrical rod, and then struck by two dies. The die which carried the main representation, the obverse, would be set into an anvil. The second die bearing the design for the reverse side, would be carved into the face of a punch. The disc would then be heated until soft, and placed upon the anvil over the obverse die. The blank disc was then struck from above with the reverse die so that the designs would be impressed into both sides simultaneously.

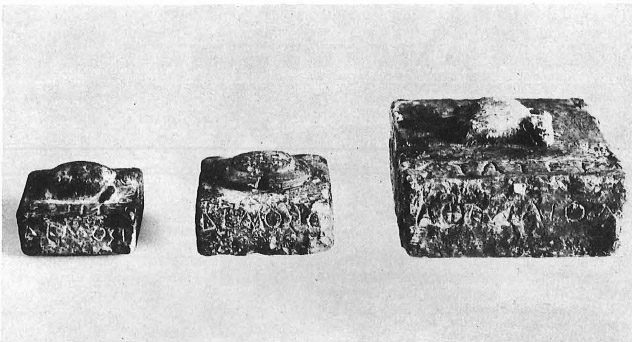

In addition to thousands of coins, the workers probably produced a wide range of other state-controlled material as well, such as the sets of official weights and measures which were made of either bronze or lead. An inscription of the second century B.C. refers to weights and measures kept in the mint, and it is perhaps no coincidence that the officials in charge of such matters, the metronomoi, held office in a building nearby.

Public slaves performed these tasks. Indeed, two are known by name. That Antiphanes, the father of the fifth century B.C. politician Hyperbolos, had worked as a lampmaker in the mint, was mentioned by one of his son’s political opponents. Two curse-tablets found at the Keramikos cemetery identify another. The inscription on the lead tablets curse one Lysanias, identified as a bellows-blower at the mint.

There must have been room within the building for the activities of more skilled workers, the artisans who carved the dies for all the coins as well as the official validating stamps used on weights and measures, jurors’ identification tickets, and a wide variety of tokens, stamps, and seals used in the daily civic affairs of the city.

Another part of the building would have housed the overseers (epistatai) of the mint, a board of ten citizens responsible for its administration. An inscription of the fourth century B.C. records a dedication by this group and was presumably set up in front of the mint.

On an average day, the mint must have been a veritable beehive of activity, fulfilling a variety of needs and serving in a very real sense as the financial centre of the city. Systematic excavation of the remains, combined with a careful reading of the written sources, is slowly breathing life into this important monument in the heart of ancient Athens.