The northeastern Aegean island of Samothrace was better equipped to receive visitors two thousand years ago than it is today. From archaic times well into the Christian era the wild rocky island in the north Aegean was the site of a religious cult, whose mysteries and initiation rites were as well-known to ancient Greeks and Romans as were those of Eleusis. Archaeological excavations have un-earthed a complex of temples and other buildings including the largest, closed, circular building in ancient Greek architecture and a stoa so large that its fourth-century B.C. builders had to artificially enlarge the hill on which it stands. Samothrace may be better known to art lovers as the home of the Winged Victory statue that stands in the Louvre.

In Samothrace today, however, the freely roaming goats just might out-number the two and one half thousand inhabitants. Lying in the shadow of its more popular neighbour, Thassos, to the northwest, Samothrace (in Greek, Samothraki) is a four-hour ferry-boat ride from Kavala or two-hour boat trip from Alexandroupolis. The abruptly rising mountains that dominate the little island’s landscape rise to a height of 1664 metres at Mount Fengari (Moon Mountain); according to Homer, the god Poseidon rose from the sea and ascended its “peak to observe the progress of the Greeks during the Trojan War. A northern coastal road connects a green and sometimes lush plain in the east to a more rolling countryside and the villages of Lacoma and Prophet Elijah in the southwest, passing in mid-route the island’s only port, Kamariotissa. From here another road leads inland to the main village, Hora, where the mountains surround the villagers’ whitewashed, terra-cotta roofed dwellings in an amphitheatre setting.

At the island’s south rim, accessible only by boat or overland by donkey, the mountains rise steeply out of the sea. Thermal baths at the village of Loutra in the north attract an older, low-income clientele. The seaside groves of towering plane trees, meadows of mint and oregano, and icy springs, attract an international clientele, in a variety of dress and undress, and campers and trodders of the ‘off-the-beaten paths’. There is comparatively little accommodation on the island, and one hopes that enterprising hoteliers will not attempt to remedy the situation. For one thing, Samothracian hens could not cope with the breakfast trade. Our queries about the curious shortage of eggs produced the tongue-in-cheek reply that the hens were doing all they could, but they just could not meet the demand of the growing number of vacationers.

Eggs are not the only thing periodically unavailable. One Italian tourist was politely requested by the local bank to return the next day to cash his travellers checks after the ferry-boat had brought cash from Alexandroupolis on the mainland. Lemons to squeeze on one’s fish come to be regarded as a luxury, and most of the local fishermen’s catch is sold to the mainland. Indeed the only thing we got out of the local fishermen was two melons tossed from their caique to our motor boat, a gesture more thoughtful than we initially appreciated. Melons were periodically harder to find than fish. (Did the ancient Samothracians live exclusively on the huge onions praised by Athenaeus?) Several restaurants in Kamariotissa serve fish, but otherwise one catches his own—and they are plentiful and bite if one is equipped to catch them.

The island’s weather is fickle and not a dependable partner in boating ventures. Winds burst from the mountains without warning, whipping the water into a maelstrom as is evidenced by the fate of two legendary fishermen said to have drowned in a sudden gale when they pulled their caique into the mouth of a stream to clean their nets. That peaceful site has been singled out for ignominious renown among the islanders who have named it Thonias’ (murderer). But Samothrace has many streams—anonymous, quiet, emptying their shallow waters into the sea.

Paleopolis, the Old City’, designates the site where archaeologists claim the first Greek colonists to Samothrace settled around 700 B.C., mingling peacefully with the indigenous peoples who ancient writers claim sprang from the earth before any other Greeks. Artifacts dating from the Neolithic period confirm the tradition, if not the origin, of an early habitation.

Near Paleopolis is the ‘Sanctuary of the Great Gods’, fifty thousand square metres cradled in the shadow of a forbidding mountain range. The origins of the Samothracian cult pre-date the arrival of the Greeks on the island, and its fame attracted adherents until the cult was forced out of existence in the fourth century A.D. Archaeological excavations have unearthed the foundations of more than twenty structures within the sanctuaries: altars, banquet halls, a theatre where the famed Winged Victory stood in an immense stoa, and buildings donated by wealthy Macedonian patrons such as Alexander the Great’s family. It was on a visit to Samothrace to be initiated into the mysteries that Phillip I met Olympia who became his wife and the mother of Alexander.

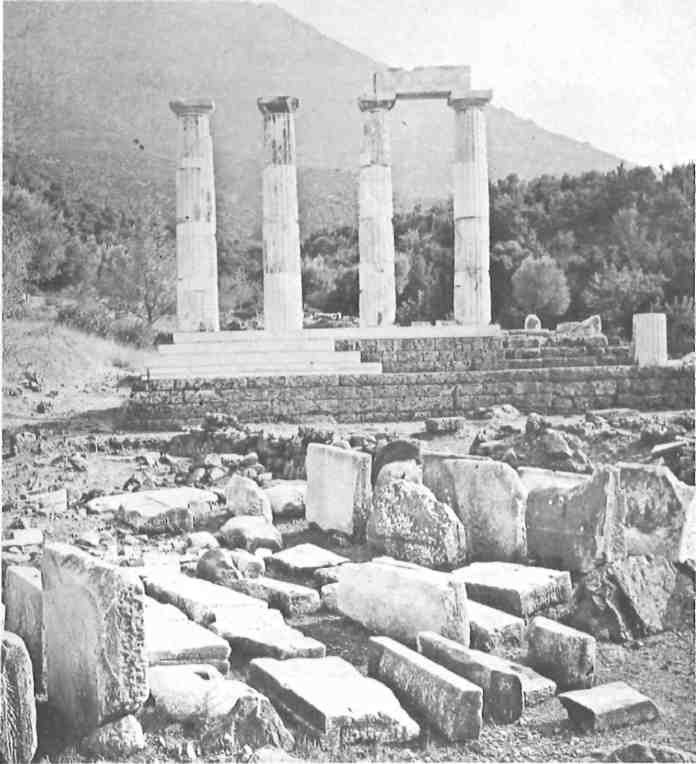

Systematic excavations were.begun on the island in 1938 by a team from New York University led by Karl Lehmann who also wrote a guide to the excavations and a history of the cult. The American group is also responsible for the small but comprehensive museum and for the re-erection of a part of the colonnaded front of the main sanctuary. The Americans were not the first archaeologists on the scene. In 1863, Monsieur Champoiseau, French consul in Adrianople, began excavations that by chance unearthed the statue of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. He shipped the remains of the statue to Paris, prompting expeditions of French and Austrian archaeologists.

Centuries before the arrival of the archaeologists, however, the ancient cult had excited the interest of Western scholars. The Samothracian cult of the Great Gods included, as at Eleusis, mysteries revealed only to the initiated, a secret they seem to have faithfully carried to their graves. Although the rites included common religious practices such as the sacrifice of animals, libations, and invocations, today’s scholars can only speculate on the exact nature of the cult, or of the beliefs about after life or fortunes in this life. What is known is that although the cult embraced a group of divinities of pre-Greek origin, the major figure was the Great Mother Axieros, who is pictured on coins seated between two lions.

The cult’s annual festival attracted an international assemblage of ambassadors and devotees from foreign states and the Greek city-states. Admission was not limited to the initiates as it was at Eleusis. The sacred site was open to all. Furthermore the Samothracian cult allowed more liberal admission to its mysteries than did Eleusis where initiation was restricted to Greeks and free people. In Samothrace, men, women and children of all nations, slave or free, could obtain initiation whose rites were a matter quite apart from the annual festival and could be performed at any time. Samothrace and Eleusis had in common two stages of initiation: myesis and epopteia. The first did not necessarily have to be followed by the second whose requirements, Mr. Lehmann speculates, may have been strict enough to discourage the lukewarm believer and perhaps even included a confession of sins unique in ancient Greek religious practice.

The initiates from other parts of the world organized themselves, once they were back home, into religious groups as “Samothrakiasts” and had congregations in numerous cities. As Mr. Lehmann points out in his guide, the practices of the Samothracian cult resemble the later Christian community more than any other phenomenon of ancient Greek religion.

Paralleling the island’s ever-growing prestige as a religious centre was recognition of its strategically important position on the sea route halfway . between Mount Ida dominating the Dardanelles and Mount Athos. Samothrace could boast many distinguished visitors such as the historian Herodotus, the Spartan King Lysander, generations of the royal house of Macedonia, the Roman Emperor Hadrian, and the Apostle Paul.

But as the centuries passed, important people no longer came to Samothrace. The splendid cult buildings were ravaged by nature and plundered by believers in other gods. By the end of the Byzantine Empire the island had drifted off into the backwaters of time and had become the property of the Italian, Palamede Gattilusio, whose fortresses still guard the coast. It has yet to be placed on any twentieth century A.D. tourist itinerary, although comparison with Delphi and Eleusis is inevitable.

But nature’s rugged framework remains unchanged: the isolating distances, that gloriously blue but fickle sea, the grandiose mountain, those forces of nature that prompted ancient man to build here his edifices to the gods.