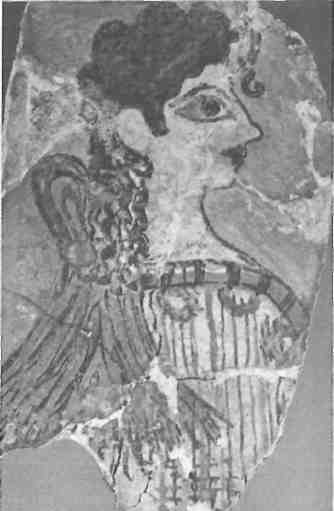

Ever since Sir Arthur Evans turned over the first spadeful of earth at Knossos in 1900 and literally began to unearth a palace, Minoan Crete has provided fertile ground for speculation. In the ensuing years, other Minoan sites have brought to light more palaces and treasures, and spawned new hypotheses. It is difficult to say why Minoan Crete continues to intrigue not only scholars but the general public. Perhaps it is the charged, intense atmosphere of the island, or the existence of such unexpected splendours as early as four to five thousand years ago, or simply the inexplicable, demanding “presence” of the Minoans. Their “look” is so immediate and modern, and like the arch-looking “La Parisienne” of the famous fresco found in Knossos, they have an exotic appeal. Whatever the explanation, the Minoan civilization has always given rise to wonderment and curiosity.

Indeed, a special breed of “Minoan watchers” has emerged, individuals from all walks of life who are fascinated by problems and issues associated with the Minoans. Some are specialists or scholars in fields which are not directly linked to Minoan studies, and many are amateurs who for one reason or another have, become “hooked” on the Minoans. These Minoan buffs can be found traveling around Crete, browsing in libraries, consulting the experts, and focussing on any item related to the Minoans.

Periodically, some issue or discovery related to the Minoans gives rise to a new “mystery”. It may begin its life as a guarded scholarly hypothesis and remain, in most cases, within the confines of the academic world. But occasionally something will be picked up by the press, attracting international attention. By the time a “mystery” blossoms in the popular media, it becomes a sensational assertion, usually involving some superlative or priority — “the oldest”, “the last”, “the first” — bolstering the public’s image of the Minoans as some unique, spectacular people attended by all kinds of miracles and mysteries.

Scholars and specialists, of course, are not above hyperbole or controversy. The last quarter-century of Minoan studies has been marked by claims and counterclaims, quarrels and feuds, heated reviews and letters to editors. Reputations have been attacked and ruined. But after the dust has settled, the specialists return to their excavations and scholarly labours, and the public is left dazzled and bewildered by yet another Minoan mystery. While public attention is directed only to the seasonal torrents and flashfloods, the great river of Minoan mysteries rolls steadily on, taking a far more interesting and profound course.

Although Heinrich Schliemann located Knossos, the ancient capital of Crete, it was Sir Arthur Evans, “the Grand Old Man” of Minoan archaeology, who conducted the excavations which revealed the remarkable civilization that existed on Crete during the Bronze Age, from 3000 to 1000 B.C. And it was Evans who named the era ‘Minoan’ after King Minos, the legendary ruler of the island. The maze-like arrangement of the buildings of Knossos, with the recurring symbol of the double axe, led some scholars to conclude that it was the labyrinth of the Theseus myth. (Labrys means double axe and labyrinth originally meant “the place of the double axe”.)

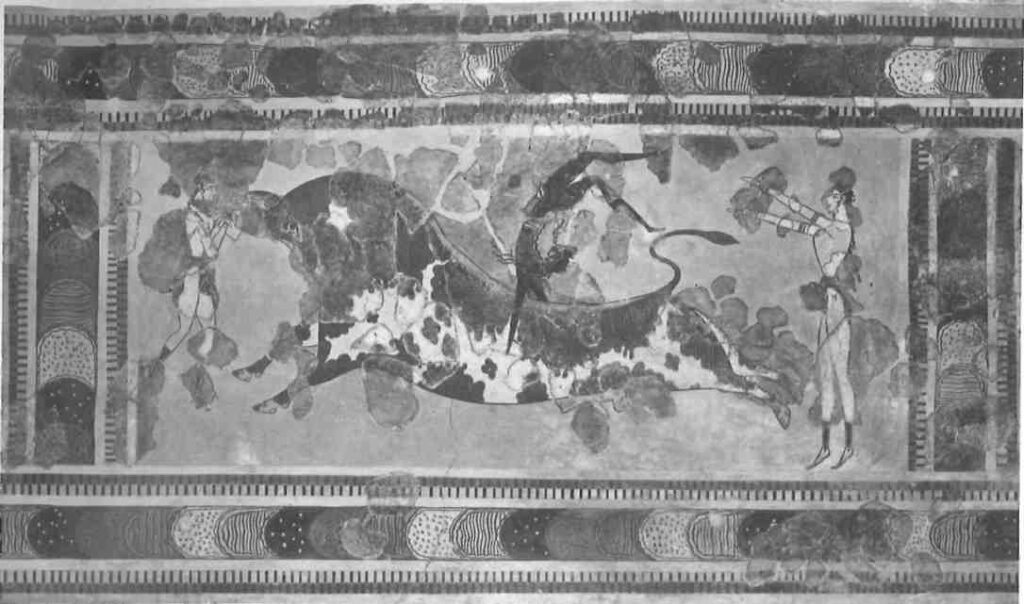

The colourful frescoes which seem to tell us so much about life in Minoan Crete, raise more questions than they answer, and bull-leaping, a feat depicted on numerous works found on Crete, remains one of the more enduring rhysteries. The best known representation of bull-leaping is the fresco Evans discovered at Knossos which is now in the Archaeological Museum in Iraklion. It portrays the leaper seizing the horns of the charging bull, swinging upward and over to perform a back flip on the bull’s broad back, then landing on the ground behind the bull. The presumably graphic explicitness of this fresco influenced Evans’s description and the generally accepted notion of bull-leaping as a sport.

This interpretation, more or less, was given wide circulation in Mary Renault’s internationally acclaimed novel, The King Must Die. Drawing on the myth of Theseus, Renault wove together fact, legend, and fancy to recreate what life in Minoan Crete might have been like. In mythology, the Athenians were compelled to make an annual tribute of seven youths and seven maidens to King Minos in order to ward off devastating earthquakes. The young people were sacrificed to the Minotaur, the half-man, half-bull who inhabited a labyrinth. These us killed the Minotaur and, with the help of Ariadne, the King’s daughter, escaped from the labyrinth. In The King Must Die, Renault departs from this aspect of the myth: the young Athenians sent to Crete as tribute are not sacrificed to the Minotaur but rather risk their lives in the dangerous sport of bull-leaping at the labyrinthian-like palace of Knossos. Renault gives a detailed account, both credible and exciting, of how they trained, including practice with a wooden bull.

That bull-leaping was practised in Minoan Crete, that it was something more than a spectator sport and of religious and ritualistic significance, is widely, but not universally, accepted. There have long been critics and skeptics who attacked the traditional version of bull-leaping. There are those who believe that all depictions should be viewed as purely symbolic and that the details deserve no more debate than the “feats” of the Olympian gods. Others argue that bull-leaping is physically impossible, supporting this declaration with confirmations by Spanish bull fighters and American rodeo-cowboys. Yet these individuals may be saying nothing more than, “It’s not our way.” There seems to be very little that human beings cannot do when it comes to physical stunts, with or without animals. Circuses are full of people doing things that “can’t be done”. Divers in Mexico dive from incredibly high cliffs into rock-strewn waters, natives in the Pacific jump from the tops of high trees by attaching ropes to their legs that stop them just short of hitting the ground, sponge divers in the Mediterranean go to depths that are normally lethal. In none of these instances is money the principal motive.

Bullfighting is, of course, most relevant to bull-leaping, particularly the less well-known Spanish variety practiced in Southern France, where the bull’s head is seized by the bullfighter who then performs various acrobatic stunts. It seems likely that human beings would be capable of developing the skill and timing that bull-leaping would require — once they felt that it was worth their while. In the case of the

Minoans, the motivation may have been a matter of status, of gaining fame and winning favour in the eyes of the ruling elite and the gods. Although dangerous, the alternative may have been less challenging and rewarding. The majority of the population was destined, after all, to spend their lives as anonymous tillers of the fields.

An article in support of bull-leaping appeared in the Spring 1976 issue of The American Journal of Archaeology. Its author, John G. Younger of Duke University, having analyzed most of the authentic Cretan and mainland Greek depictions of bull-leaping, concluded that bull-leaping was actually practised at some time. The leapers, he believes, never touched the bull’s horns, but simply dived over the horns and head, landing on the bull’s back on his or her hands (females seem to have participated in the sport), and then turning a back flip before landing on the ground behind the bull. Since many of the later representations show the leaper in a static, lifeless pose above the bull, Younger theorizes that bull-leaping probably had died out and the artists were then depicting an action they knew only by verbal account.

Another interesting theory inspired by the famous bull-leaping fresco is that of Charles F. Herberger. Although neither a classicist nor an archaeologist (his field is English Literature), he became intrigued by the Minoans. Herberger considers that the important question is not whether the leaping was actually performed, but rather the meaning of the fresco itself with the bull and three figures. In The Thread of Ariadne (Philosophical Library, New York City, 1972) Herberger theorizes that the fresco is a solar-lunar calendar used for ritual as well as secular purposes — from timing religious festivals to predicting tides and scheduling agricultural activities. The basis for his claim is his analysis of the border design of the fresco, not the main subject of the leapers, although they are crucial to his interpretation and the bull itself is seen as a spring – sun symbol. In the border design, Herberger finds a sequence of ordered regularity related to the seasons of the Cretan agricultural year. “The picture as a whole,” he says, “is emblematic of the sacred marriage of the sun-king to the moon-goddess, of his death, and of his union with her after death, and finally of his rebirth through her.”

Neither Younger nor Herberger has had the last word on the bull-leapers but they have fueled further debate on the Minoan mysteries, some old, some new. They have been largely ignored, however, by a public expecting a Minoan mystery to be sensational.

One book that did cause a minor sensation —and gave birth to a new “mystery” involving another aspect of Minoan civilization — was The Secret of Crete, published in German in 1972 and in an English translation in 1974. Its author, the late Hans Georg Wunderlich, was a reputable German geologist. When he first visited Crete he had no desire “to poach on the archaeologists preserve”, but while touring the palace of Knossos, his geologist’s eye noted a number of features that seem to have been overlooked by most students of the Minoans: gypsum was used in places, such as stairs, where one would not expect to find such a soft stone. Moreover, the stairs did not seem to have been worn down while the palace was in use. Proceeding from this observation, Wunderlich concluded that Knossos had not been a palace for the living elite of the Minoans but a necropolis —a city of the dead.

Not surprisingly, the publication of Wunderlicrfs thesis was attended by fireworks. One corollary to be drawn from it, however, seems to have been lost: Wunderlich may have provided a useful alternative to the widely held vision of aristocrats, beautiful, bare-breasted women, calculating merchants — a veritable agora where the corridors and stairways were jammed with people rushing to ceremonies, sacrifices, or the arrival of yet another shipment of gold. There may have been much less activity, and far fewer people, than has been “imagined. The entire palace, as the largest building in a sizeable town, may well have been permeated by a sense of isolation, insecurity, and even perhaps fear. Many of the great palaces and homes of the rich and powerful in our own time remain barely used — and their residents obsessed by what might be called a “fortress mentality”. When thinking of the palace of Knossos, the model is probably not the Versailles of the Sun King but the Escorial of Phillip II. If Wunderlich had something similar in mind with his “palace of death”, it might have led to some valuable debate, but the true mystery may have eluded the mystifier. Wunderlich’s construct razed the very Minoan Crete he wished to illuminate, and led to very little reappraisal.

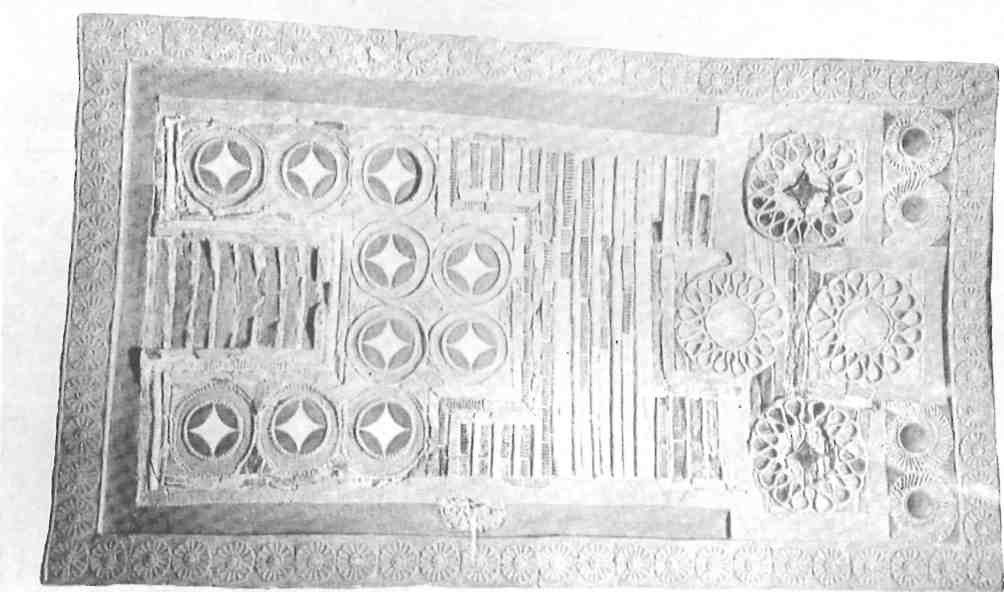

Another puzzle that has engaged scholars and spawned new mysteries is the famous game board from Knossos, which is on display in the Iraklion Museum. Visitors from all over the world gaze at it for a moment and then pass on. Found by Evans, it was dubbed the “draughts board”, the British term for what Americans call “checkers”. Evans did not give much thought to the object. Over the years, sporadic attempts were made to work out some game for the board. (Similar boards have been found in Egypt and, indeed, Homer mentions that the heroes passed their time with games.) In 1957, H.J.R. Murray published his History of Game Boards Other than Chess (Oxford University Press), and in what was considered the definitive work, he announced it was not a game board.

There the mystery rested, not so much solved as shelved, until Robert Brumbaugh published a short piece in the Spring 1975 American Journal of Archaeology. He announced that the Knossos board was indeed for a game — and he knew how to play it. Brumbaugh argued convincingly that the Knossos board was used for a variation of the traditional “race game” in which two players, throwing dice, move pieces around the board and try to capture each other. Brumbaugh admits it is a relatively dull pastime, simple as it is, but it might have been enlivened if the players had money riding on the game. As with the other theories, Brumbaugh’s “solution” to the draughts-board mystery is probably destined to remain a conjecture.

The game board may seem a bit too esoteric for the mass media, but deciphering scripts reeks of secret codes and espionage, and “lost” languages have always attracted crowds of onlookers. The Minoans left more than their share of undeciphered scripts. The two scripts used by the Minoans in Crete (and by the Mycenaeans in mainland Greece) were named by Evans Linear A and Linear B. Linear A remains a riddle but in 1952 the English architect and cryptographer, Michael Ventris, deciphered Linear Β and showed it to be the oldest known form of Greek, dating from 1500 to 1200 B.C. Born in 1922, Ventris became interested in Linear Β at the age of fourteen after hearing Sir Arthur Evans lecture on the subject. Ventris worked on this mystery while completing his studies and serving in the Royal Air Force. After the War, he set about his task with even greater zeal, using a method of statistical analysis. In 1952 he announced his success over British radio. The Cambridge linguist, John Chadwick, joined him in his work and together they collected and presented the evidence substantiating Ventris’s theory in the now historic paper of 1953, “Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Mycenaean Archives”. (Ventris died in an automobile accident in 1956 at the age of thirty-four.)

The Phaestos disc found, as its name indicates, at the palace of Phaestos, presents yet another mystery. It is a terracotta disc about seventeen centimetres in diameter, with pictographic signs stamped on both sides in a spiral sequence. Since the signs appear to have been punched by a metal “type”, the disc is sometimes called the first example of printing by movable type. No convincing translation has been made, but it continues to intrigue and periodically a “solution” is offered. It has been variously interpreted as a catalogue, hymn, and calendar. One ot the most recent theories emerged in 1977 when a Polish scholar, after ten years of work, announced that he had deciphered it, and that it was a prayer, in an archaic form of Greek, asking the gods to help a King.Khalkeleus and to save the town of Itanos.

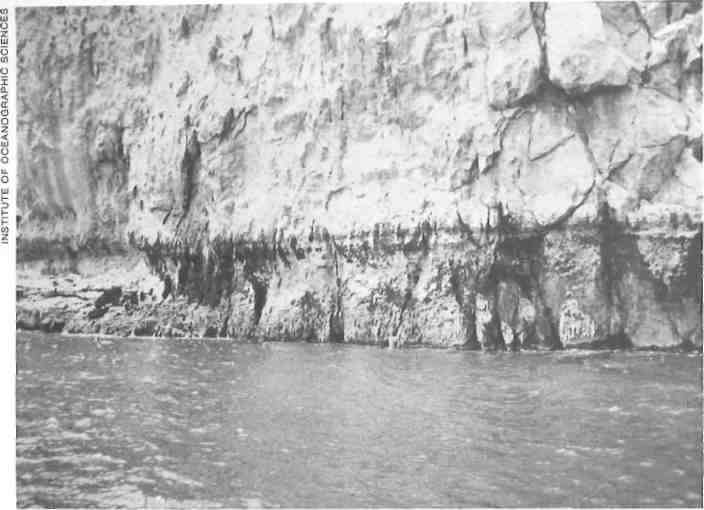

And so the never-ending stream of Minoan mysteries continues. Although the public’s taste may tend to run toward superlatives and the sensational, the scholars continue the patient detective work that produces steady results. In recent years, for instance, a team of British scientists led by Nicholas Flemming spent countless hours — many of them underwater — taking the measurements that explain why some Minoan coastal sites are submerged and others stranded high above the water’s level. In setting aside the old theory — that a cataclysmic tilting of the whole island once occurred — Flemming has shown instead that the rise and fall has been an ongoing process with local variations.

Is there a possibility that we will run out of Minoan mysteries? Unlikely. The experts can’t even agree on how and when the Minoan civilization ended. Inevitably, this has been linked with Lost Atlantis; but that’s the ancestor of all mysteries and demands its own story.